Blue Blood: An Incomplete History of Posh-Bashing

The Sloane Rangers handbook, which lovingly skewered the Carolines and Henrys of another era, has just turned 40. But this grand tradition of poking fun at the plummy-voiced has become even spicier in the decades since...

Just as crazy people don’t believe they’re crazy, most posh people don’t believe they’re posh. Poshness, after all, is a relative concept (like fame, or evil, or the space-time continuum near a black hole.) It all depends on where you’re standing and what trousers you’re wearing at the time. This is a delusion by comparison. It is a vanity of small differences. So long as you’re looking in the right direction — into a more exclusive racing enclosure, or a neighbor’s better partridge drive — there’s always someone posher than you are.

The mania starts with the sort of girls who wear brimmed hats and over-the-knee-boots at Polo in the Park (not posh), and goes all the way up to the Royal Family (probably posh.) But even Prince Harry, I suspect, would tell you that he’s not really that posh — that he doesn’t wear yellow cords, for example, and hasn’t been to Polzeath in years. Do you remember when Prince Andrew dismissed one of his debauched, Epstein-flavoured highland bacchanalias as simply a “straightforward shooting weekend”? That’s because, to him, there’s nothing more straightforward and down-to-earth as a weekend’s shooting. Real poshos, he’d tell you, do it for a whole week instead, and probably in places like Africa or Antarctica or something. And really, really posh people don’t shoot animals all — they look after them in their homemade safari parks and have baby lions in their crumbling drawing rooms, like that Tiger King chap, only with more gout and marginally less crack cocaine.

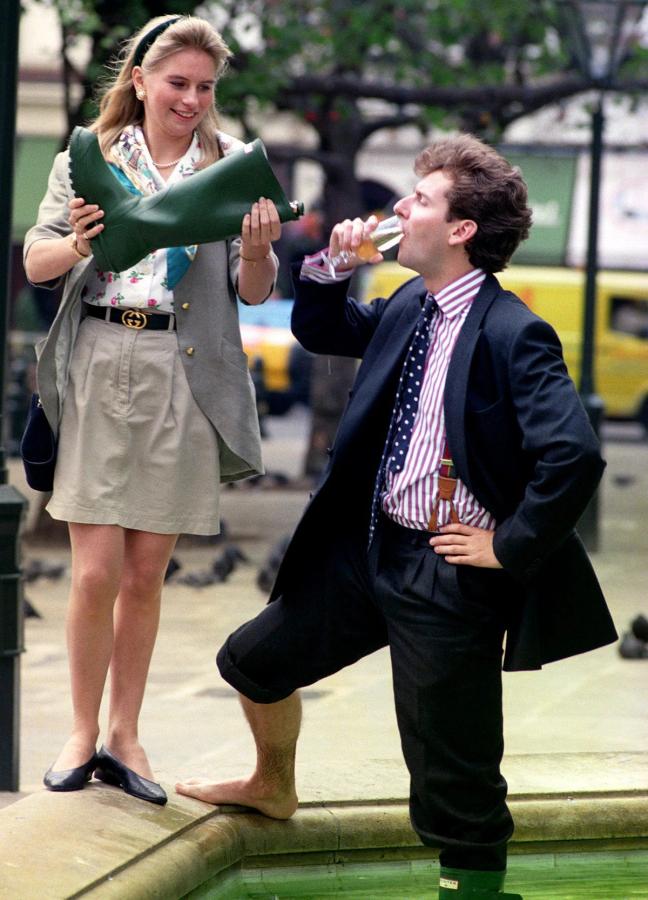

A Sloane celebrates winning Harper & Queen’s ‘Sloane Ranger of The Year Award,’ Sloane Square, 1991

F Scott Fitzgerald said that going broke happens slowly, and then all at once (he wasn’t posh, by the way, and neither was Gatsby — but we’ll get to Americans later). It’s the same with realising you might be posh. At first, the pinpricks of light appear one by one, in the manner of cigarette burns in the marquee ceiling of a 21st. (Rule of thumb: the more expensive the marquee, the more likely some Radley boys are to climb to the top at 2am and share a soggy cigar in celebration of Hugo fingering someone’s sister behind the portaloos.) But then the realisation comes on all at once and at terrifying speed, like a Downe House girl who’s swallowed too much MDMA at the house music festival on her neighbour’s estate (I’m told). It could be something as simple the way your mother pronounces “hour” (“It’s a two arr drive from Bordeaux, Neil”).

And then the word is out. You are not like the rest. You are different. You are the other. You are the chinless few. You are the problem. Yes: there’s no getting around it — you are posh, alright. And then the anxiety really kicks in.

Because being posh is the affliction that keeps on giving; the punchline that always lands. Long after jokes and jibes about the Welsh, or mother-in-laws, or people from the Midlands have been deemed problematic (and quite right too), the posh will remain fair game. They’ll probably be perfectly happy with that status quo, too (as long as we’re involved!). Self degradation is the posh person’s national sport, after all, and there’s nothing posh people like more than a national sport. And anyway, this has been going on for some time.

"Being posh is the affliction that keeps on giving..."

Take the case of the Sloane Ranger’s Handbook. Published in 1982 by Peter York and Ann Barr (two journalists at Harper’s Bazaar) the book traced, for the first time, the dot-to-dot (or point-to-point, if that’s a more palatable reference) of London’s pink-cheeked classes. A galloping new breed of Henrys and Carolines was frozen eternally in aspic — their habits and dress codes and linguistic ticks set down in bullet-point lists and detailed diagrams: pearls and Barbours and limping dogs and Gucci loafers and Purple Silk Cuts and Renault 5s and cocaine and nannies and Henrys and knitwear and Lanson and cookery schools and not owning a chin and never crying at funerals.

It was affectionate rather than nasty; jolly, insider-y, downstairs loo stuff, to go next to the faded photo collage from your 18th birthday and a picture of your uncle in Grand Cayman in a fun hat. But when you pin down a rare biological specimen for dissection, it’s very rare that the specimen emerges unscathed. At the precise moment the authors of the Sloane Rangers Handbook captured their subject, they extinguished it, like a National Geographic photographer stealing the soul of some undiscovered tribesmen deep in the Amazon with his mysterious flashing box.

What’s more, the general public largely missed the joke. Some ‘aspirant’ readers (“men in covert coats, women with Diana-like velvet breeches,” wrote Peter York in Prospect) would turn up at book signings and tell the authors which public school they were sending their children to, in search of some plummy endorsement. Others were furious and offended, in a vaguely North London sort of way. Either way, under exposure, the Sloane ideal began to wane and fade, and had disappeared entirely by the nineties. (Interestingly, the latest season of The Crown — with its scenes of a young Diana-about-town — has helped to revise the look of the Sloane Ranger, in a sort of Instagram moodboard-y way. You see plenty of pictures of the Princess in cycling shorts these days, and knitted sweaters with sheep on them, and certain brands cashing in on the renewed interest in frump. But, as York himself reminds me: “this was never about clothes — it was about class.” So that chapter, at least, remains firmly closed.)

"The Preppy Handbook trod a fine line between the roasty and the toasty..."

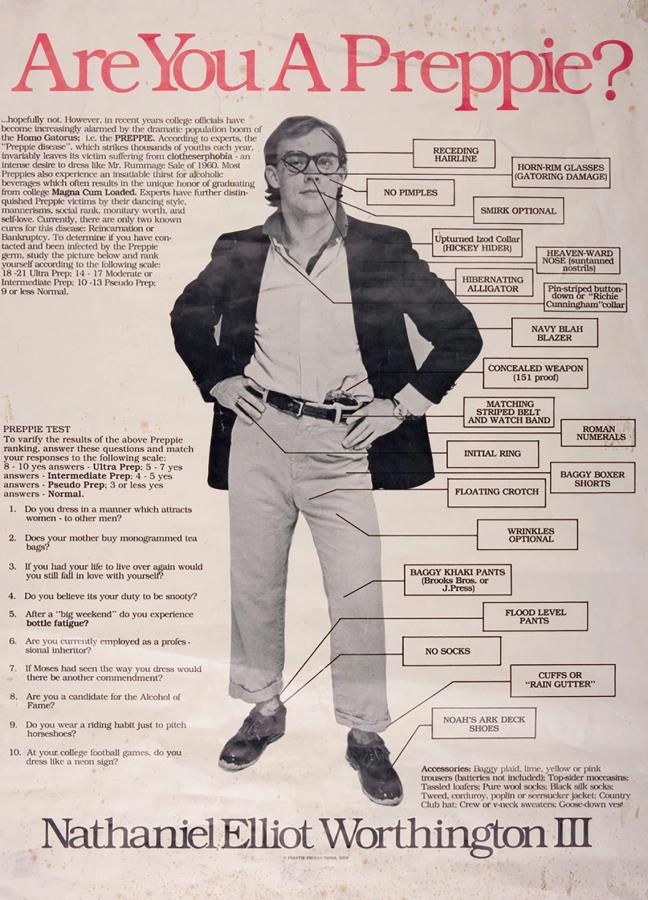

The book itself was a callback to an earlier exercise in moneyed skewering: the Official Preppy Handbook. Released in 1980, the perma-dog-eared volume was all about American posh people, if that isn’t a contradiction in terms. (It is — though I have sometimes heard Nantucket described as “more English than the English,” which is fun because it insults both parties simultaneously.) The symptoms of ‘Prepdom’ were worryingly familiar — sporting attire taken far beyond a joke; an obsession with animals over people (there is a chapter devoted solely to ducks — “the most beloved of all totems”); and a doughy, sexless, whiteness all round. Everyone has an unthinking dedication to the way things are done. (“It’s really important to have no imagination,” the author, Lisa Birnbach, said of preppiness in 2010 in an interview. “There’s a kind of laziness.”) And there is, of course, an effortless obsession with schools.

Most striking, reading it now, is the finely-trodden line between the roasty and the toasty. Birnbach, at the time a 21-year-old Village Voice staff writer, has described herself as an “insider-outsider”, and says she used to wear a black Lacoste polo to show that she was preppy, but still “downtown.” It’s affectionate but barbed, in this way: a playful elbow to the ribs by the fireplace. It certainly makes you think twice about wearing a jumper tied around your shoulders. But in general, with their green polo shirts and yellow trousers and pink complexions, the citizens of Prepdom appeared dozily harmless — circus clowns with trust funds. And they seemed, even 40 years ago, to be a dying breed. Unknowing privilege, inherited pudginess, familial safety nets, weak-chinned coziness, prep school in-jokes — surely, the book seemed to say, these braying goofballs were in their twilight years? Surely they’d shortly find themselves bred out of the gene pool? Surely the jig was up?

Harry Enfield’s Tim Nice-But-Dim

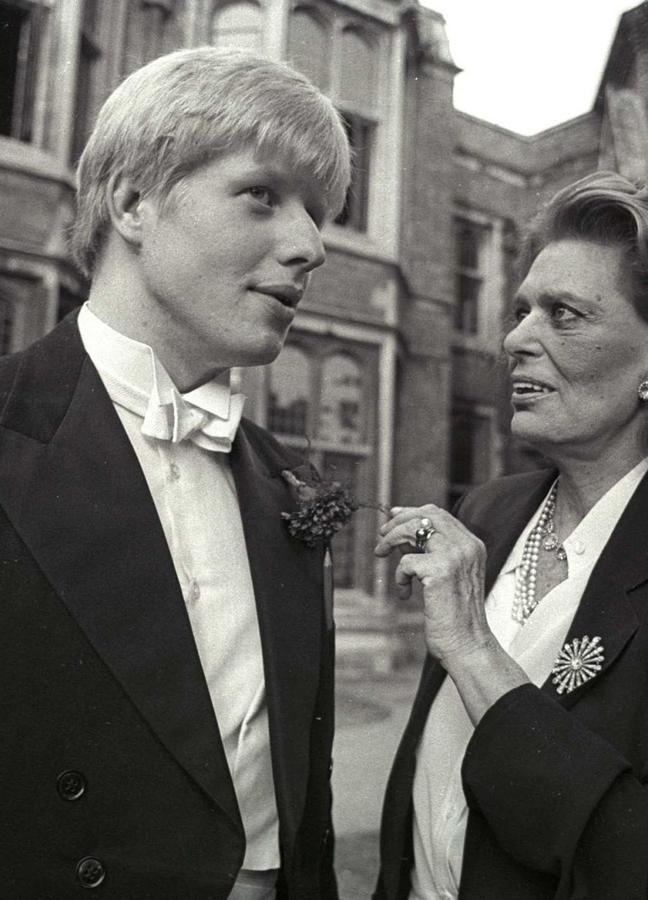

Four decades hence, and we’re still wondering. In 1990, Harry Enflield’s Tim Nice-but-Dim was the prototype. He wore hooped rugby shirts under a gold-buttoned blazer (which was supposed to make him look like a dreary anachronism, but now, in fact, makes him look as if he’s appearing in a Drake’s advertorial) and often name dropped the Sloaney Pony in Parson’s Green, which remains a guilty pleasure among chins even today (lovely new front garden, if you haven’t been down recently). Some saw him as a soothing balm to the rigged casino of the Old Boys network — if posh chaps really were this thick, they reasoned, even nepotism couldn’t save them. But others saw in him the galling tendency of the public school boy to land always on his feet, like a cat in cords.

Tim was brought to life by Enfield (armed with a monstrous set of teeth), but he was created by Nick Newman (a Sunday Times cartoonist) and Ian Hislop. They both went to Ardingly College, in Sussex (me neither), and said they’d known plenty of Tim NBDs in their time. “They all ended up going to the City to do jobs they didn’t understand, yet ended up making oodles of money,” Newman has said. When Tim was briefly resurrected by Enfield for a live tour in 2015, however, he wasn’t a banker — he was a cabinet minister. That career pivot, of course, was no accident. And it’s around this time that the spice of the conversation kicks up a notch (from a masala, say, to a vindaloo), and the jokes become all too real.

Gap Yah, A viral youtube video from the Cameron era, wasn’t actually particularly funny

The ritual of posh-bashing had lain largely dormant throughout the early 2000s. There was no salient public school punchbag to quote on the drive down to Salcombe; no cosy satirical guidebook to give to your boorish god son. But then, in 2010, a chap called David Cameron was elected Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. (You can call him Dave, because none of his friends do.) The rap sheet for DC is now well known: Eton, Brasenose, the Buller; wife the daughter of a Baronet; weekends in Chipping Norton with Jeremy Clarkson (Repton) and Charles Dunstone (Uppingham); polo shirts and bad shorts on holiday; head like a blancmange. Didn’t put his penis in a pig’s head during a Piers Gaveston all-nighter — but then again, didn’t he? When Colonel Gaddafi fell in Libya, Cameron was on holiday in Polzeath (“What more do I want? A great day on the beach, and I’ve just won a war,” he said, according to Sasha Swire’s diaries). All in all, he was just too smooth, looking back — too Home Counties; too friend-of-a-friend. I rather liked him.

Osborne and Cameron were described as “two arrogant posh boys"

There had been public school boys in Number Ten before — most former Prime Ministers, in fact, went to fee-paying schools. But we’d never had anyone who felt quite so P.L.U. Suddenly, the gammon was driving the bus. The harmless clowns of the 80s and 90s had come for your benefits. And the posh-bashing — long dormant like a nasty case of Lime’s — flared into feverish form. (The recession of 2008 — prodded along, one always felt, by a general private school insouciance — didn’t help.) In a 2012 interview with the Financial Times, Nadine Dorries, a Tory MP, summed up the new sentiment neatly. The country, she said, was “”being run by two public school boys”, referring to Cameron and Chancellor George Osborne — “two arrogant posh boys who show no remorse, no contrition, and no passion.”

Naturally, the period was rich with satire, take-downs, memes and punchable faces. Some of it wasn’t particularly good: that irritating “Gap Yah” character on YouTube was galling chiefly because it was so broadly overplayed — no nuance, no detail, no subtlety. Genuinely posh people pronounce it “yerr”, not “yah.” It came out during my Fresher’s Week in 2009, and anyone quoting it was usually worth a wide berth in the college bar (which I obviously never went to.)

Much better was Archie Curzon, the Clapham-botherer and self-regarding fly half in the Don’t Drop The Egg video series. It hit the mark because actor and creator Orry Gibbens (Cheltenham) knew people just like dear Archie — prep school heroes living forever in a looped highlight reel of the Rosslyn Park Sevens ‘03 — and clearly even liked some of them. Better still, perhaps, was High Renaissance Man — another 2010 YouTube film — which was filled with pathos for its perma-rutting Bristol University chiller, James. (“I wish you had died and not Max!” he says at one point, mimicking his scolding father.) James does his History of Art dissertation on Banksy, and plans to host a club night called “Swallow Your Tongue.”

There were highbrow efforts, too. Laura Wade’s play Posh — about the gruesome antics of a thinly-veiled Bullingdon Club — debuted two months before David Cameron’s election victory in 2010 (though she’d been planning it since 2007, when the photos emerged of Boris Johnson, George Osborne and Cameron posing, like floppy-fringed peacocks, on those infamous steps at Christ Church.) It was the perfect encapsulation of the born-to-rule, loftily disconnected, blank-cheque-your-way-out-of-it airs that many smelt around the Tory leadership at the time. Sometimes it all felt a little on the nose — there’s a moment when one of the characters screams: “I’m sick to fucking death of poor people,” which seemed a bit much. But it was always interesting in the softer, calmer moments away from all the carnage and snobbery. Tellingly, the characters often felt charming, bright, winningly funny — even when their comments were drenched in insincerity. (The Guardian, in an interview with Wade, even acknowledged that “the boys were actually rather fun”.) It helped, perhaps, that many of the club members were played by good looking, charismatic, likeable public school actors — James Norton, Henry Lloyd-Hughes and Kit Harrington were front-and-centre in the stage version; Max Irons, Josh O’Connor, Sam Claflin, Freddie Fox and Douglas Booth in the 2014 film adaptation, The Riot Club. (Genuine Bullingdon Club members, in my experience, are rarely quite so chiselled.)

"You classist gimp," James Blunt wrote to Chris Bryant MP...

This provided a pleasing yet accidental meta-commentary, too. At around that time, it seemed, you couldn’t move for privately-educated poshos scooping up gongs in leading roles: Eddie Redmayne (Eton), Tom Hiddlestone (Eton) Benedict Cumberbatch (Harrow), Dominic West (Eton), Damian Lewis (Eton). It all got a bit much for Chris Bryant MP, then shadow Culture Minister, who decried the trend of “Downtown programming” that dominated the airwaves. “I am delighted that Eddie Redmayne won [a Golden Globe for best actor], but we can’t just have a culture dominated by Eddie Redmayne and James Blunt and their ilk,” he told The Guardian.

James Blunt (Harrow) soon published an open letter in retaliation, which began “you classist gimp,” and went on to explain that “it is your populist, envy-based, vote-hunting ideas which make our country crap, far more than me and my shit songs, and my plummy accent.” He went on to explain that his boarding school privilege hadn’t helped him a jot in the music industry, and had often counted against him. But when Eddie Redmayne won his best actor Oscar that year for The Theory of Everything, and opened his acceptance speech with the phrase: “I know I am a lucky, lucky man”, you knew he was referring to his upbringing as much as the favour of the Academy.

Filthy, rich, spoilt, rotten: the cast of 2014’s The Riot Club

Not everyone was as certain in their views as Bryant or Blunt. It struck me at that time, from about 2012 to 2015, as austerity tightened and DC approached his second election, that a kind of love-hate fascination with posh people gripped various parts of the media. It wasn’t just Downtown Abbey. There was a 2014 BBC2 documentary series called Posh People: Inside Tatler, which celebrated, with a sort of nostalgic silliness, the subjects and characters of the original society magazine. Made in Chelsea reached its peak in this time, and still had some genuinely posh people in the mix (though Chinnocio’s Chin Dictionary — the satirical Instagram bible on poshos — was pretty accurate when it described it as “a TV show by non-chins for non-chins about non-chins thinking they’re chins”. Now, as far as I can work out, it’s just Love Island auditionees and people who sell nutritional supplements.)

That world and its characters had a charm and a sheen, even while they looked silly and contemptible. (The thronging, white-jeaned crowds at places like The Bluebird on the King’s Road, meanwhile, are almost solely due to the glitzy, Diet Posh lifestyle sold on the show.) Poshness looked frothy and fun, for a moment, even if you disdained its foundations and hated its chummy superiority. And its jester-in-chief — the latin-quoting, perma-bumbling, schoolboy-haired chortler — was Boris Johnson, then riding high on a successful London mayoral term and plotting his way to the very top. People liked Boris against their better nature — he wore his vices on his face, and was at least sincere in his insincerity. He’d never pretend to enjoy hot baked goods in the way that Cameron had, or lie about supporting a football team he didn’t. And he held all the beguiling traits of the boarding school paradigm — charm, learning, silliness, and an ability to shilly-shally his way out of a scrape.

"Boris Johnson is the posh paradigm's Jester-in-Chief..."

This past year has shown us just how far that act can be stretched until it grows desperately thin, or gives way entirely. It’s remarkable — despite (or maybe because of) all the bumbles, affairs and untruths — just how far the ploy can go. And one is aware constantly of the eerie, nagging sense that Boris Johnson will be able, at the last moment, to Bertie Wooster his way out of even a global pandemic. But I have noticed, in the last four years (and very likely due to Brexit, where Cameron’s out-of-touch nonchalance sashayed the country straight into a potentially disastrous referendum) a new toughness and heat to the conversation. Privilege, in any sense, is no longer cool or interesting. The chinny pose and poise begins to look nasty when you feel it might have genuine consequences for your future. I have friends who have stopped wearing their signet rings (horror of horrors!) for fear of flaunting a certain upbringing, in the way that driving a gold Lamborghini through central London no longer looks simply naff — it now looks offensive.

“It’s important for me not to blame anyone — we don’t choose what background we come from, what school we go to,” said Laura Wade, diplomatically, on the eve of the Riot Club’s release. “But it’s how you choose to behave and use the lucky cards you’ve been dealt at birth [that’s important]” Things still get personal. In March 2019, a tweet went viral that lampooned four Telegraph columnists based on their names: Hamish de Bretton-Gordon, Sophia Money-Coutts, Boudicca Fox-Leonard, Harry de Quetteville. The replies were sometimes pretty unpleasant, in a guillotine-y sort of way.

Sophia Money-Coutts wrote a column a few days later in response, acknowledging that that she had been“lucky, lucky, lucky,” and on a “greasy path which I know most others haven’t had available to them and of which I am very aware. So I make jokes about [my name] and try to be funny because I understand the whiffs it gives off.” But you can tell this sort of reverse snobbery rankles: “I thought we weren’t supposed to take the piss out of people for their ‘funny’ names any more?” she wrote. “Or make assumptions about people based on nothing more than what they’re called?” (Money-Coutts also explained that a Guardian columnist once tweeted that her name made her want to ‘die’, which I can slightly sympathise with: once, in 2014, when my name appeared in Tatler as the slightly jokey “Joffy Bullmore”, someone tweeted: “never have I wanted to punch someone in the name more.”) The tweet even gave rise to a little parlour game: “Your telegraph columnist name is your first pet, the road you grew up on (hyphen) an object in front of you,” we were told. So I am Tilly Wardington-Totebag, which is quite exciting.

The Chin Dictionary: the last word in posh-skewering

In the end, though, no-one could be more brutal to the posh than the posh themselves. Perhaps it’s an acknowledgement of their own absurdity; perhaps it’s an in-built guilt at their privilege; perhaps it’s a sado-masichism learned long ago at boarding school; perhaps it’s the fact that no-one can take themselves that seriously in a Schoffel. Whatever it is, the posh don’t need anyone else to take them down a peg or two — they’ll keep it in the family, thanks very much. The finest dispenser of this knowing self-flagellation is, perhaps, the Chin Dictionary, which has happily just been transformed from its Instagram format into a handsomely-bound stocking filler book. It has picked up the mantle where the Sloane Rangers Handbook et al left off, and updated things for the modern era. It is also lovingly crueller than any Twitter mob.

The blurb on the back rather sets the tone. A “chin,” the guidebook explains, is: “An individual shaped by years of upper class in-breeding ever since Willy the Conqueror dropped in for a cup of tea. Understanding the true nuance’s of a chin’s characteristics is akin to translating dolphin clicks, if the dolphin clicked, downed a beer off a Stubbs painting, chucked a cartridge into his drawing room fire for a laugh, then raised your rent. The chin club takes a century to get into and one usage of the word ‘toilet’ to leave.

“If you wear bright colours un-ironically, can trace social connections back to the paleontological era, and think ‘meritocracy’ is a nightclub in Bristol — welcome on board.” And if not — count yourself exceedingly privileged indeed.

Read next: Am I posh? A New Year’s Eve checklist

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.