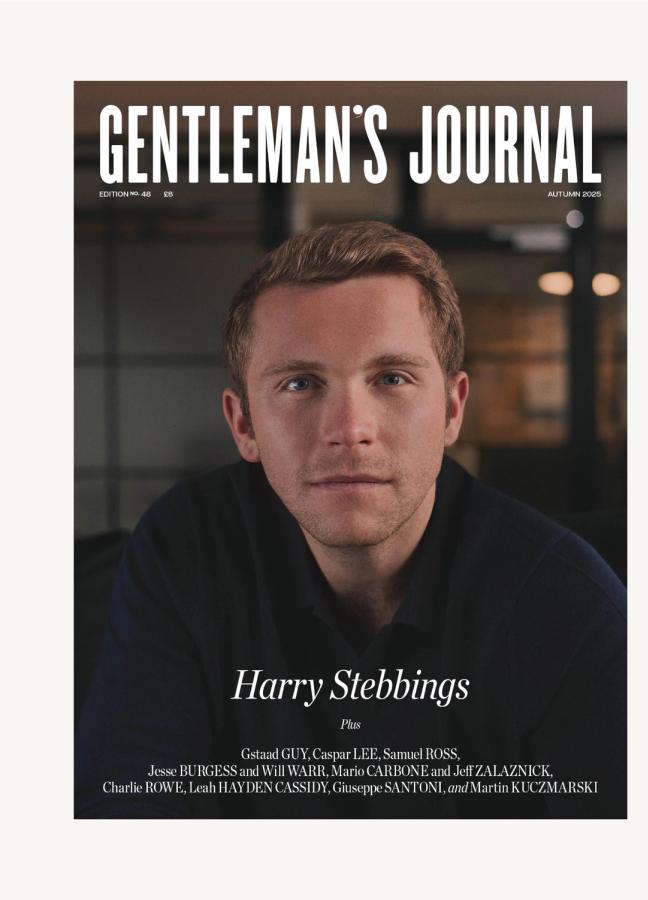

“You really have to be unwaveringly obsessed..." Harry Stebbings on six-day work weeks, The Social Network, and AI

The podcaster-turned-VC has released 1400 episodes and backed 13 unicorns to date. But his real motivation, he says, might well lie in his childhood.

- Words: Joseph Bullmore

- Photography: Barney Curran

We’re here, really, because of the Social Network. Harry Stebbings was thirteen years old when he first saw the film — David Fincher and Aaron Sorkin’s brooding portrayal of the early days of Facebook — and knew instantly what he was going to do with his life. But whereas a lot of ambitious young people walked out of that movie wishing to one day become a tech founder (or, in my case, join the Porcellian Club at Harvard), Harry thought: “Gosh. I want to be a venture capitalist.”

“I realised that this was the greatest job in the world,” he says now, sitting in the podcast studio of his handsome offices in Marylebone. “I thought: I can marry what I love, which is meeting the smartest people in the world, with finance and investing, which is venture capital.” And all this at 13, remember, when most of us dreamt of becoming footballers or firefighters or, um, members of the Porcellian. At seven, he tells me, his favou

rite magazine was Campaign, the advertising industry’s trade paper. I was reading the Beano. And only for the pictures.

Everyone should be building a personal brand, Harry tells me a little later on. It’s fair to say that a certain lovable precociousness has long been a major strand to his. Harry was 18 when he started his podcast, ‘The Twenty Minute VC’, from his bedroom in 2015. The premise, as you might hope, was to interview leading people from the venture capital world in 20 minutes or less. “But I didn’t know any VCs, and I had no money,” he said. “I just had a 50 pound ‘Iceball’ microphone. And so I started cold-emailing VCs.” His first guest was Guy Kawasaki, the Silicon Valley big dog who was one of Apple’s most influential figures in the 1980s. Since then, the show has rolled on like a juggernaut for more than 1,400 episodes, with notable guests including founders Daniel Ek (Spotify), Reid Hoffman (LinkedIn), and mega investors Bill Gurley (Benchmark), Doug Leone (Sequoia), and Howard Marks (Oaktree). A friend in finance put me onto the show early on, and said, in what I think was a compliment, who the hell is this kid? My memories from those first episodes are of Harry as a mile-a-minute, hyper-confident, eerily informed host — completely wise beyond his years. Did he really feel that way at the time?

"There's nothing more constraining than a vision..."

“My mother taught me that there’s nothing you can’t achieve,” he says now. “And that only you know the limits of your own abilities — and even then, you are much better than you think.”

“I hate visions,” he continues. “There’s nothing more constraining than a vision. You will never be able to foresee what you’re able to achieve. When I started the podcast I wanted to be an associate at this venture fund in London. Well, in three years I raised $150 million and was a founding GP [General Partner] of a fund. If I constrained myself to the vision that I had, I would have been massively undershooting my potential.”

“And so you have to be micro ambitious — but not pretend to be arrogant enough to know what’s going to happen in three to five years.” At the end of 2016, Harry was named ‘Entrepreneur-in-Residence’ at the fund Atomico. In 2018, he co-founded Stride VC with Fred Destin. In May 2020 — less than five years after he recorded that first bedroom episode — he started his own fund, 20VC. In the years since, it has raised over $800 million and invested in 13 unicorns. Its latest initiative, Project Europe, is backing the most ambitious young founders across the continent, with the goal of boosting overall GDP.

Across those 1,400 episodes of the podcast, Harry has noticed three commonalities between his hyper-successful guests (many of them billionaires and decabillionaires.). One: “they moved around a lot in childhood,” Harry says. “Meaning they were forced to assimilate with different cultures and communities and make new friends.” Two: “They were very good at gaming.” And three: “They started something entrepreneurial very young.”

Harry certainly fulfills the latter criterion. “All throughout my teenage years I was doing arbitrage on Motorola RAZR phones from eastern Europe and selling them at boarding school. I was doing Kindle direct publishing on the GCSE student notes I had,” he says, making “a thousand or two thousand pounds a month as a fifteen year old.”

What was he like as a kid? “I didn’t really have friends,” he says now. “It deeply affected who I am today. I was very much alone. I used to go to the bathroom at break time because then other people wouldn't see that I had no friends. And I was very insecure and unhappy in my own body as well. I was very obese when I was young.”

“I felt very much like an outsider. Everything that I loved, no-one else liked. I loved Andreessen Horowitz and interest rates,” he laughs. “And at 13, that wasn’t very interesting to anyone else.”

"There is nothing that I will not do to win..."

“That’s really important to who I am, because so much of what I do is trying to prove to the world that I am actually worth something,” he says, before adding with a smile: “And there is nothing that I will not do to win.” As a founder story, I’d back that.

Does he have friends now? “My best friends are my business partners. They work with me day in, day out, and they're very great and dear friends. But I’m very happy now as a human,” he says. “Life has really been good to me.”

Besides, he says, his highly-disciplined schedule doesn’t leave much time for socialising. “If you want to be the best, you really have to be unwaveringly obsessed.” At 20VC, the team follows a 9-9-6 philosophy: 9am to 9pm, six days a week. He makes these conditions clear to potential team members upfront. “I tell them: ‘this is the place where you will do the most meaningful work of your career, and you'll make more money here than you ever will anywhere else. But if you want to take the baton, be ready to work fucking hard.’”

Sunspel T-shirt, £95, sunspel.com

Workplace culture, Harry says, should not necessarily be conflated with workplace happiness. (This was taught to him by Nikolay Storonsky, the founder of Revolut.) “People thrive when they are developing personally and when they're developing financially,” he says. “So the only thing that you need to do [as a boss] is focus on winning. When you win, people are happy.” But even this, he says, has to be tempered with a certain humility. “I'm always learning,” he says. “And as a leader, I never ever want anyone to feel like they can't tell me that I could have done something better or differently.”

What piece of advice does he most often find himself giving to founders, or those starting out in their careers? “The most important thing is just to start,” he says. “Most people fail because they don’t start. And the second most important thing is that this is a game of who can survive the longest. People fail because they quit. The truth is, most people won't care about what you do for long periods of time and you have to get comfortable doing it.”

"The biggest problem with the UK is that it's cool to be negative..."

Others may fail because they chase fads, of course. What are the tulip-manias of our time? “The majority of AI. When you see AI on your toothpaste or toothbrush,” that’s a bit of a red flag, he says. “People are slapping AI on everything.” Then there’s protein. “The misuse of protein in nutrition is just a disgrace. Protein is not all the same. When you shove synthetic protein into a protein bar, it is not the same as having eggs. So that trend of protein mislabeling is just some to-the-moon bullshit,” he laughs. “And I think there's a trend around negativity in London, too, actually.”

It has become almost fashionable, he notes, to grumble about the city. “But this is a great place to be. The culture is fantastic. The biggest problem with Europe and the UK specifically is that it's cool to be negative. One of the best things in the US is they believe in you when you don't believe in yourself. And I want more people in the UK to say yes to amazing young talent before the young talent sees their own potential. Our job is to enable a generation of incredible entrepreneurs to build things that matter. That's really important and that requires a ‘yes’ culture.”

Much more worrying than the state of London, Harry believes, is our mental diet. “I would never, ever let my children on social media,” he says. “It's the most poisonous thing we have now.” He acknowledges that this is an interesting admission from someone who’s success (and latterly investing edge) has come from a certain social virality. Having seen some of these social companies from the inside, what does he know that the rest of us don’t? “That we are fundamentally trained to make you addicted.” Speaking about a gaming company, he describes how it is “17 NASA scientists who fundamentally should be building rockets to further humanity. But they instead are wiring game mechanics, so we can make your children addicted to play games and then pay for them,” he says. “And all of it is to increase shareholder value.”

The irony, he acknowledges, is that it is these same tech companies, and the investment ecosystem that supports them, that will likely solve some of the big problems facing humanity, too. “I do believe that AI will create very meaningful solutions to a lot of health problems,” he says. “And that actually that you will have unbelievable breakthroughs in the most incurable of diseases, and that your loved ones will be around for a huge amount longer. That is incredible.”

“Because really, technology can be an incredible enabler for brilliance,” Harry concludes. And brilliance, in his case, can clearly be an incredible enabler for technology.

Subscribe to Gentleman's Journal now to receive this issue to your door.

Read next: Gstaad Guy on wealth, self-expression, and gentleness.