Words: Harry Shukman

Controversial books are often likened to hand grenades, blowing a hole in the literary scene. With Answered Prayers, Truman Capote detonated an altogether more brutal form of ordnance. When a chapter of his book was published in 1975, it was as if the diminutive writer had tunnelled, like a Great War sapper, underneath the duplex apartment buildings of the Upper East Side, then lit the fuse on an apocalyptic load of gelignite. The blast engulfed countless members of the glitterati.

Capote had been working on Answered Prayers — which cause more trouble than unanswered ones —for decades. At first, he said it would be his magnum opus. Then he began calling it his posthumous novel. “Either I’m going to kill it,” he said, “or it’s going to kill me.” What he hadn’t reckoned on was the damage it would do to his friends.

A darling of New York’s upper echelons, Capote was a trusted confidant of glamorous ladies and society princesses — the Swans, he called them — who dished their worst secrets to him. There wasn’t an affair, abortion, divorce or death among the elite that he didn’t know about. “Instead of a shrink, I had Truman,” said the Italian noblewoman Marella Agnelli.

Trusting in the old adage that writers should write about what they know, Capote stuffed Answered Prayers with these beau monde confessions, much to the horror of the Swans. When a preview chapter ran in the November issue of Esquire, all hell broke loose. Capote, the Swans said, was Judas in tweeds. Months after the extract was published — one of seven planned in the book — a reporter observed “society’s sacred monsters have been in a state of shock ever since”.

La Côte Basque 1965 was the chapter’s title, referring to the year in which Capote’s avatar visits a French restaurant off Fifth Avenue. Everyone who’s anyone goes to La Côte Basque for lunch, and today Capote — in this story called Jonesy — spots Jackie Kennedy and her sister Lee Radziwill, the socialite Babe Paley and her sister Betsey Whitney, the artist Gloria Vanderbilt and her actor friend Carol Matthau.

In the extract, some of these women are presented as themselves; others are lightly fictionalised but easily recognisable. Jonesy is here with his pal Lady Ina Coolbirth, a beautiful socialite with an imaginative interpretation to wedding vows. She is afflicted by dyspepsia and “perma- nent bad breath” due to her thirst for Louis Roederor Cristal.

Jonesy and Lady Ina – a thinly veiled version of the fashion icon Slim Keith – sit down in a banquette. It all goes downhill from there.

Getty Images

Jonesy tunes in and out of his conversation with Lady Ina to follow the exchanges at nextdoor tables, and what emerges is a portrait of socialites – based on real people – who are desperately unfulfilled. They are so bored with life that they have begun to fantasise about suicide, sighing that to pass out drunk in the snow would be a “lovely” way to go. They spend their days hammered and their nights in a prescription pill fugue, all to escape the pain of unhappy marriage and the tedium of extreme wealth. Even in their brief moments of lucidity, they spout nonsense.

“There is at least one respect in which the rich, the really very rich, are different from other people,” drones Lady Ina. “They understand vegetables.” Their brains seem to have taken on the consistency of the soufflé Furstenberg that is La Côte Basque’s speciality (“a froth of cheese and spinach into which an assortment of poached eggs has been sunk”).

So gone is Gloria Vanderbilt, Jonesy observes, that she is unable to place the strange man who greets her on his way out the restaurant. “Your first husband,” prompts her friend Carol.

The lunch continues in a sordid airing of the jetset’s dirty laundry: some of it real, some of it invented, and the rest somewhere in between. Joseph Kennedy, JFK’s father, is accused of rape. Johnny Carson, the talk show host, goes missing. When he finally surfaces after two days, he calls up his wife to say he’s been on a bender in Miami and cruelly puts on the line some girl he’s hooked up with. Babe Paley’s husband Bill cheats on her with a “cretinous Protestant size forty” whose menstrual blood covers the sheets with “stains the size of Brazil”. Bill spends the next few hours frantically scrubbing the sheets clean, trying to dry them in the oven, and slipping the damp linen back on the bed before his wife comes home.

These stories dropped jaws and sent eyebrows into the troposphere: “shit served up on a gold dish”, exclaimed one reviewer. But the real shock came with Capote’s description of the Ann Woodward scandal: a 1955 reversal of the Oscar Pistorius case. Ann, a model and socialite living in Oyster Bay, hears an intruder in the middle of the night, and picks up her shotgun to bang both barrels at him — before discovering that the “him” in question is in fact her husband William.

She got away with it, despite the fact that William’s body was found naked inside a shower. “The water was still running,” Lady Ina explains, “and the shower door was shattered with bullets.”

“The next time I see Truman Capote I’ll spit in his face”

The story goes that Ann was worried that William would divorce her, disinheriting her children and giving her the boot out of high society (she was an arriviste from Kansas). So she planned an elaborate murder, Capote wrote, laying groundwork for her trigger-happiness by spreading rumours that burglars were on the loose in their swanky neighbourhood of Long Island.

The weirdest thing about the whole affair, at least as Capote de- scribed it, was that William’s mother Elsie — a true Wasp — publicly supported Ann because she didn’t want to create a scandal. She reportedly bribed the police to hold a sham inquest so it wouldn’t bring charges for murder against her daughter-in-law.

Elsie would invite Ann to dinner parties to show their friends there was nothing to see here. This uneasy truce lasted for twenty years until Ann heard about Capote’s plans to revisit the death of her husband in Esquire. A few days before the magazine was published, she took her life. “Well, that’s that,” Elsie said after Ann’s suicide. “She shot my son, and Truman murdered her, and so now I suppose we don’t have to worry about that anymore.”

If Elsie’s reaction to La Côte Basque 1965 was more sanguine, the rest of New York went ballistic. When the chapter came out, the Swans mobilised. They raced through the article and saw through the light dusting of fiction Capote had sprinkled over the facts — facts they told him in confidence. How could he! “The next time I see Truman Capote,” snarled Gloria Vanderbilt, the husband-forgetter, “I’m going to spit in his face.”

Slim Keith went one further. She had been mocked as Lady Ina, the soused divorcée pursuing new husbands who only had to be “rich” and “technically alive”. Keith made the Swans agree never to speak to Capote again. If she ever saw him walk into the same restaurant, she would cut him. “It was unjust and dreadful to put those words in my mouth,” she said. “I’ll never forgive him, never.”

This wasn’t satire. It was betrayal. “Never have you heard such gnashing of teeth, such cries for revenge, such shouts of betrayal and screams of outrage,” said a New York magazine journalist covering the fiasco. “What did Capote write that enraged so many? Oh, just everything he ever heard whispered, shouted, or bruited about.”

“He’s ridiculous; a candied tarantula”

So why on earth did he do it? Trumanologists are divided, and it will be interesting to see what the upcoming TV show ‘Feud’ (created by Glee’s Ryan Murphy, starring Tom Hollander as Capote) makes of this. One school of thought suggests that Capote wanted to send up Manhattan society for treating him like a performing monkey. He had been described by gossip columnists as the “little secret to charity benefits”, a party piece who could be relied on to trot out yarns about beating Humphrey Bogart at arm wrestling and uproarious one-liners like: “When I think of Paris, it seems to me as romantic as a flooded pissoir, as tempting as a strangled nude floating in the Seine.”

(Even if Capote felt his role as a dinner party zinger-merchant was too onerous, he was extremely good at it. Here’s one of my favourites, just while we’re on the subject. “I guess the reasons I stay in New York,” he once drawled, “are because you can buy a bowl of onion soup at four o’clock in the morning, have a suit made to order in Times Square, if you really need it, at four o’clock in the morning, and you can also buy the sexual favours of a policeman at four o’clock in the morning.”)

Capote, by his own admission, was an odd character whose very appearance and helium-pitch voice were shocking. “People don’t love me,” he once said. “I’m a freak. People are amused by me, fascinated by me, but people don’t love me… And why I’m so outrageous, so ridiculous, so squeaky and carrying on is simply to relieve them of this sudden embarrassment. If I’m so outrageous, all they can do is laugh and then it’s OK.” Assuming the role of court jester, and recognising that he was not a friend so much as a “candied tarantula” as one observer put it, must have taken its toll.

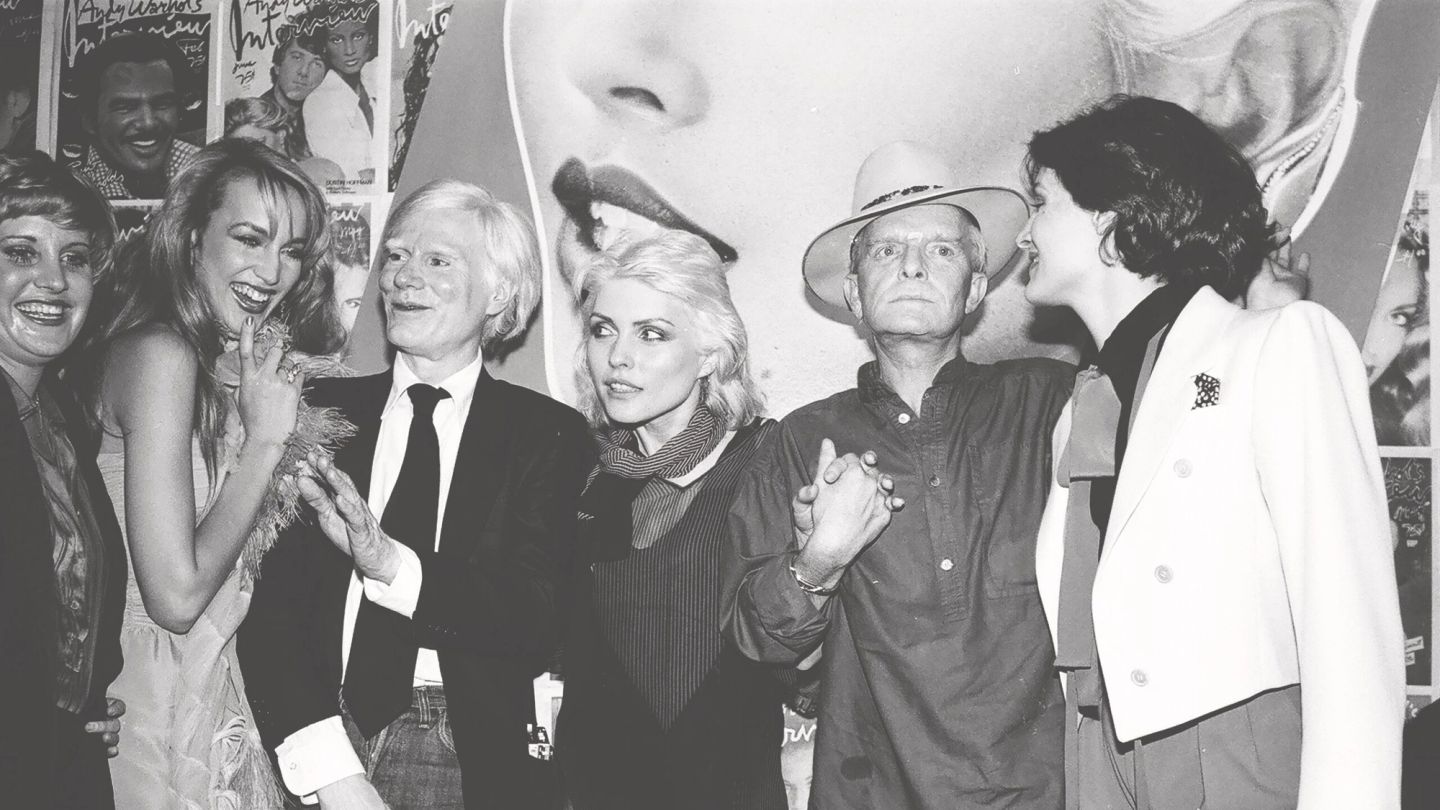

Capote with Lee Radziwill, one of his ‘Swans’ and the sister of Jackie Kennedy, in 1969. In the book, he described the sisters as: “a pair of Western geisha girls.” Getty Images.

The world of extreme wealth that Capote inhabited was ripe for a send-up. Since Breakfast at Tiffany’s (first a 1958 book, then a movie starring Audrey Hepburn) and In Cold Blood (a 1966 ‘nonfiction novel’ about murders in rural Kansas), Capote had sealed his reputation as a top celebrity author. He moved in the same circles as the very rich, discovering that for the most part, they were very bored. As his friend Dotson Rader described, the jetset that Capote now belonged to all “think the same way, have the same desires, have roughly the same amount of wealth and all bore each other silly”.

Andre Leon Talley, the late Vogue impresario, noted that the Swans were the sort of women so concerned about appearance that they had their maids iron their cash so each bill would be crisp. This was a world that needed documenting.

Capote was one of the few openly gay men in public life at a time of deep homophobia. His mother took him, as a child, to the doctor for hormone shots to rid him of his homosexuality. Now an accomplished adult, Capote was invited to dine at the top table of Manhattan society despite his sexual orientation. But not everyone was welcoming, according to George Plimpton, a Capote biographer. Ann Woodward, the shotgunner of Oyster Bay, once sneered at him: “Yes, that’s that faggot Truman Capote.” Perhaps Answered Prayers was his way of getting his own back. In any case, Capote’s friends noted that he had a wicked streak, a desire to shock. The TV presenter George Page said Capote told him he wanted to “do something dramatic or the world is going to get tired of me”.

What seems clear, given how badly the Côte Basque scandal erupted, is that Capote had made a grievous miscalculation. Gerald Clarke, another Capote biographer, recalled a conversation prior to publication in which he told the author to prepare for angry reactions. “Naaaah,” Capote responded. “They’re too dumb. They won’t know who they are.” He was bullish that his book would go down well, telling Dick Cavett, the talk show host: “No one’s going to be the least bit annoyed with me unless they’ve been left out.”

At most, he anticipated a slap on the wrist, according to the author John Knowles. “He imagined that these ladies were going to sit around and say, ‘Oh, that little rascal, look what he’s done this time! Isn’t he too much!’ Then they’d invite him to the yacht.”

But, for the most part, there were no more yachts, no more lunches with his favourite Swans, no more access to the inner sanctum. Capote was confused, complaining that his friends should have known that gossiping to a novelist and hoping he would keep schtum is like putting a squirrel in front of a wolfhound in the belief they will become friends.

“What did they expect?” he said. “I’m a writer, and I use everything. Did all those people think I was there just to entertain them?” He had been talking for years about Answered Prayers, and how it would be based on real life. A minority of Swans accepted this. “Writers write,” said Carol Matthau. “Anyone who doesn’t know that is silly.” It wasn’t enough. Capote’s attempts to bury the hatchet failed. He sent Slim Keith a note that optimistically read: “I’ve decided to forgive you.” She did not reply, and called a lawyer to inquire about a libel suit.

“I thought they’d come back”

Only as the dust began to settle after the chapter’s explosive publication did Capote realise what he had done. His best friends were lost to him. He locked himself in his flat in the United Nations Plaza, sobbing on his bed, repeating the words: “I didn’t mean to, I thought they’d come back.” Kate Harrington, a daughter figure in Capote’s life, said it was like they’d suffered “a death in the family”. Babe Paley had been one of Capote’s closest confidants. He once wrote of her: “Mrs. P had only one fault: she was perfect; otherwise, she was perfect.” Now, like so many others, she was ducking his calls. Paley would never speak to him again. When she died from lung cancer, three years after the extract came out, Capote wasn’t invited to her funeral.

It was around this time, friends recall, that Capote began drowning his sorrows. Until then, he had said in interviews that alcohol was largely incompatible with his line of work. “Drink is the worst thing that can happen to any writer,” he said after the publication of In Cold Blood. “The creative act has to be the most disciplined action in the world, the mind has to be so surgically balanced that anything that distorts it makes for false art.”

On rare occasions, a small glass at the end of the day could help grease the brain’s gears and restore momentum to a tricky paragraph. Otherwise, Capote insisted that writers must treat their profession like athletes: “You have to stay in constant training.”

That, in the late sixties, was Capote at the top of his game. Now that the Côte Basque chapter had cost him his friends, he quit training. He began hitting the bottle, discovering prescription pills and, this being the seventies, cocaine. Lots and lots of cocaine. Liz Smith, a New York magazine journalist who profiled Capote, recalled beginning a night out at his flat and being gleefully presented with a big glass bowl of gear.

“Our mouths kind of flapped open, because I had never seen so much cocaine,” she said. “I mean, it had to be $10,000 worth.” At the time Studio 54, the legendary nightclub, was in full swing and Capote became a regular in the VIP rooms underneath, where all sorts of sticky behaviour ensued. Suspended from the ceiling in the main hall was a giant display of a Moon man hoofing coke up his nose with a spoon. The club was a popular gay disco and Capote, as one of the first out gay men in American high society, was “a kind of hero”, according to the Rolling Stone founder, Jann Wenner. When Capote showed up, a friend recalled, the crowd waved and parted like the Red Sea. Moses had arrived.

“Isn’t it too bad Proust didn’t have something like this,” Capote sighed about the club. “Sometimes when I’m there I think about all the dead people who would have loved 54. People like Toulouse-Lautrec, or Baudelaire, or Oscar Wilde. Cole Porter would have loved it.” While everyone else was disco dancing, Capote did the jitterbug, a long extinct 1930s jazz jig. As fun as it was, it wasn’t Capote’s first choice of leisure. Bob Colacello, who worked with Capote at Interview magazine, thought deep down the writer “wished that he could have just gone to lunch with Babe Paley”.

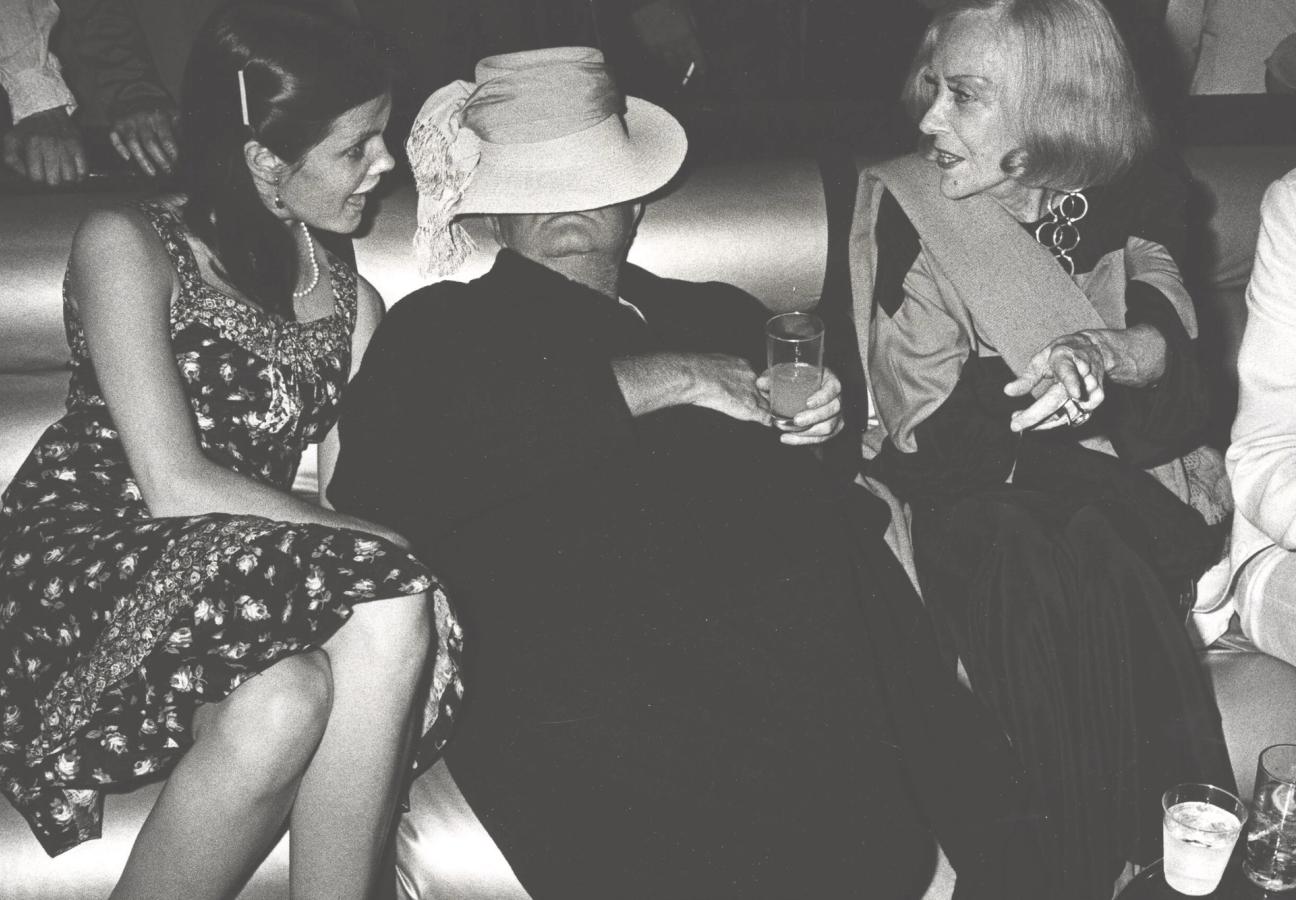

By now a seasoned caner, Capote’s literary output began to suffer — not to mention his health. He had extended the deadline for Answered Prayers three times now, and it still showed no sign of being finished. He was out of control. Capote appeared at dinner parties and monologued incomprehensibly before passing out. His diet of booze and pills made him alert one moment but spangled and drooling the next. One pal saw what he thought was a “bag lady” shuffling around the Upper East Side before realising it was Capote. John Richardson, the actor, invited him back to his flat to make him tea, but by the time he came in Capote had necked half a bottle of liquor and had to be bundled into a cab.

Getty Images

His binges became epic and sad. A friend remarked on Capote’s habit, during a Rolling Stones tour he was meant to cover, of lying on the floor in his undies with a load of pills lined up on his naked belly, picking them up one after the other and washing them down with Jack Daniel’s.

In 1978, he stumbled onto the talk show of Stanley Siegel, slurring horribly, his eyes blinking independently of each other. Siegel asked him about his problems with booze. “Alcohol is the least of it,” Capote burbled. “It’s the joker in the card pack.” Siegel asked what would happen if Capote continued drinking and taking drugs like this. His reply was bleak. “The obvious answer is that eventually I’ll kill myself without meaning to.”

Stints in rehab dried him out, but never for long. Once off the wagon, he suffered hallucinations of burglars coming to take his cash and jewels, episodes of bed wetting, drunkenly lurching through busy roads, passing out on the pavement. The sharpest wit in American letters had lost his edge. Even a book reading in San Francisco’s Herbst Auditorium went wrong: Capote kept losing his place, returning to passages without remembering he had already read them. To save face, the organiser went onstage to say there was a bomb threat and the building had to be evacuated.

Perhaps sensing the end was nigh, Capote booked a one-way flight to Los Angeles to stay at the home of Joanne Carson, the Swan married to the Miami philanderer from the Côte Basque, still a close friend. Telling her he felt fragile, Carson joked: “Truman, don’t you dare. You die, and I’ll never speak to you again.” When his breathing became difficult, Capote begged Carson not to call an ambulance, and died in her arms saying “Mama”. He was only 59. For years he had been in pain. Gore Vidal reacted to his rival’s death by calling it “a wise career move”.

And what of Answered Prayers? An incomplete version of three chapters was published. The full manuscript is rumoured to be stashed in a Greyhound bus station in Nebraska, or a bank vault, or long since incinerated in Capote’s fireplace, or that it was never finished at all. “But my dear, so few things are fulfilled,” he once said. “What are most lives but a series of incomplete episodes?”

Want more literature? Richard E. Grant reveals his eight favourite books…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal member. Find out more here.