The second coming of Jesus: London’s favourite Maître d’ dusts off his little black book

After 38 years at Le Caprice, Jesus Adorno now runs the show at the brilliant Charlie’s in Brown’s Hotel. Just don’t talk to him about square tables…

It’s hard to know where men like Jesus Adorno come from, and I mean that quite literally. Just what is that trick of appearing seemingly from no-where? That ability to shimmer silently and smilingly into view? The gift of teleporting into a room — or a conversation, or a birthday supper — at just the right moment? You never see Jesus Adorno coming. (Or Jeremy King, or Jeeves, or Jesus Christ, come to think of it — the four J’s of miraculous service). But then, all of a sudden, there he is — and there you are, and here we are, and how are you, and isn’t this all lovely, and it’s so kind of you to fit us in again.

Some people go to restaurants for the food, or at least they say they do. Some people go to restaurants for the atmosphere, by which they mean other people in similar clothes to them having a slightly better time. But real restaurant go-ers — the four-or-five-a-week professional lunchers; the early-onset gouters — go simply to come back. For them, the chief joy in this changing and frightening world is the familiar smile, the shared history, the outstretched palm — and the glint in the eye of the maitre d’, like some friendly older brother, welcoming you back inside for more.

I’ve stolen that last bit — the brother bit — from Jesus Adorno himself, in fact, arguably the most beloved and connected man in London restaurants. (It’s Jesus, by the way — pronounced like Zeus, not like Mr. Christ. Different gods; similar stature around these parts. Oh, and it’s actually Jesus Adorno Sanabria, in keeping with the Bolivian tradition of preserving your mother’s maiden name. But Londoners got confused, and the toffs thought he was missing a hyphen, so Jesus simplified things on his business card long ago.)

The sibling analogy is about right. Adorno tempers a sort of conspiratorial chumminess with just the gentlest sense of wisdom and authority. And people love him, flock to him, follow him, with all the joyful lunacy of family ties. Le Caprice, which the man helmed for 38 years, was a good brasserie with a glitzy history, and it shone through (despite its funny old location) when everything else in London was a little drab and dull and, well, Londony. (‘Le Caprice: Behind the Ritz but Ahead of Its Time,’ ran the original billboard advert when Jeremy King and Chris Corbin first opened the joint in the early 1980s.)

"Leaving was like losing my life, losing my heart..."

But then the ‘foodie’ revolution happened, and everyone became a celebrity, and suddenly beautiful David Bailey prints no longer buttered quite as many parsnips — until, by the end, you suspected that the only reason people were popping in was for the familiarity, that sense of the storm in a port; for Jesus, if we’re honest. To Le Caprice, Adorno was like Attenborough is to the BBC, the Queen to the monarchy — such an integral and wholesome and singular part of the institution that you wondered how things might continue once they were gone, not that you could ever imagine such a thing. Then the pandemic happened, and the restaurant shut its doors for good, and Richard Caring (owner of Caprice Holdings, which commands the Ivy group, Sexy Fish, Annabel’s et al, along with Le Caprice) called Adorno into his office. “He told me he didn’t have a new site for me, and that I was to stay on furlough.” Adorno recalls. “So I decided to give in my notice the next day.”

Adorno with Sir Rocco Forte, the hotelier behind Brown’s

“It was hurtful”, Adorno says about the decision to leave, admitting that his goal had long been to stay at the institution for 40 years. “But I had no choice.” For a while, he thought about diving into restaurant consultancy (“and at least the money would be better!”), believing he could never find a place to enchant or beguile or provoke him in quite the same way as Le Caprice had — the first power restaurant in London, and his first love. (“It was like losing my life, losing my heart,” he says. “I spent half of my life there…”)

But then he walked into Charlie’s, the grand, beautiful, historic dining room of Brown’s Hotel on Albermarle Street, owned by the formidable Sir Rocco Forte — and suddenly things changed. John Keats had nightingales. Warhol had soup tins. Jesus Adorno has rooms. They appear to spark something off in him, and he in turn can transform them into something new entirely. Where you or I might see four walls, a carpet, and somewhere to chop up a little Chicken Milanese, Adorno sees the room’s source code and its swirling DNA, like Neo in The Matrix, only in navy fresco wool. “This is what convinced me to take the job,” he says of the handsome view from double doors of the dining room out across its length. He has been tweaking the place ever since he arrived in the autumn of last year, swapping out square tables for more sociable round ones wherever possible. (No-one likes eating at square tables,” he says with a wince.) At the same time, he has transformed the once-vaguely-chilly ‘Siberia’ of the room (“The Picadilly End”) into the real power spot, coalescing around three excellently-positioned banquette tables, dotted with navy financiers. But they’re all good. Nowhere is out in the sticks. Everywhere has the right mix of see-and-be-seen. Real masters have the confidence not to overhaul, but to tweak.

Adorno first came to England from his native Bolivia in 1972, when he was just 19. He was a kitchen porter and server at Downside School in Somerset, before becoming a pot washer in a restaurant in Beaconsfield. Slowly he moved closer to London, hopping jobs ever six months or so — until he came to Le Caprice, in 1981. That was during its first flush — the height of the Princess Diana days, when the original Sloane Ranger would post up at the vaunted table seven several times a week, and everyone else would pretend not to notice. (“Table seven used to have a very clear pecking order,” Nicholas Coleridge once told me. “Then the poor Princess of Wales died, then Jeffrey Archer disappeared off the scene for a couple of years, and Leslie Waddington [the art dealer] ate out less — and so NC got it.”)

"I want to make this restaurant a club within a club..."

Forty years hence, and the man is good service personified; a geiger counter for bonhomie. (“England made me,” says Adorno.) Over dressed crab at Charlie’s, he talks softly and quietly, as if letting you in on a secret or a joke — but has one antenna raised at all times, assessing the mood at each table on the restaurant floor. This is inherent, but it can be taught, too — and Adorno is attempting to sculpt the battalion of young , keen service staff here into mini-Jesuses, if that isn’t some sort of blasphemy. (Several of them serve us while we eat, and it strikes me that there is probably nothing quite so daunting in this trade as pouring out wine under the kindly eye of Adorno.) “I have taught them to recognise the customer’s needs,” he says, adding that anticipation is the key skill here: learning the tells of body language and posture to spot when a diner’s eyebrows are about to be lifted; when mustard might soon be required. “But most of all, they need to think about what would make them want to come back again.” For all his soft skill and youthful features, Adorno is a pragmatist and a businessman at his core, and he knows that repeat business — a cabal of regulars who treat this place almost like a canteen — is the best way to survive in ultra-prime Mayfair.

“I want to make this restaurant a club within a club,” he says. “You don’t have to pay membership, but you come in because you’re a regular, and you have tables you like, you recognise some people, and they recognise you. And when I walked into this room for the first time, it gave me the confidence to start taking advantage of my black book again.” Adorno removes a large black phone from his pocket and places it on the white table cloth. “This has everyone in it — everyone, And it’s backed up in the cloud, so don’t worry.” A huge proportion of the bookings at Charlie’s already come directly to him via that phone, and he shows me a clever app where he can see the tables being booked in real time, and who is booking them, so he knows when to apparate, from the ether, by each tableside, and in which order. Which means, I suppose, that Adorno — or, more specifically, the 40 years of charm, grace and guile that got him here — is now perhaps Charlie’s most valuable asset. (Though the food, overseen by Adam Byatt of Trinity, is lovely, too. Best dressed crab and chicken milanese in town, and you can quote me on that.)

Adorno reminds me however, that if this place is to last as long as Le Caprice did, it’ll have to do so without him. (The maitre d’s former haunt will now be turned into an Italian restaurant, by the looks of things, while it seems possible that its sonorous name will be deployed somewhere else in the Caring empire — or perhaps even undergo a national roll-out, as happened with The Ivy brand.)

“So This is my last swan song,” Adorno says. “I’m lucky that people might come here to see me. But I need it to live on after I’ve left.” This eventuality seems distant and remote, like flying cars or 3D printed Puligny Montrachet. The maitre d’ game tends to keep one young, after all, and Adorno is the youngest 70-something-year-old in town. Besides — he’s only just getting started here. There are many more lunches to come. “And I’ll make sure this place is the best it can be.”

“But all I would like, a few years after I leave, is to come back one day for lunch. And they’ll say ‘oh, Jesus, how are you?’” he laughs. “Then I’ll have a glass of wine, maybe two, a plate of pasta —and then, when I come to pay the bill, they’ll say: ‘don’t worry, Jesus. This one’s on the house.’”

Read next: A rare medium, well done: The enduring brilliance of The Wolseley

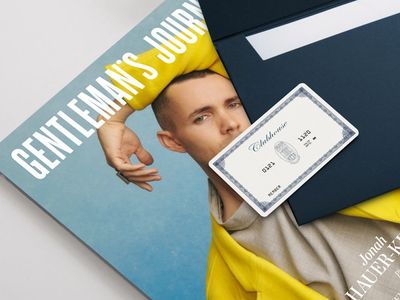

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.