The Cyber War: is it here?

The latest big cyber-attack only took down a few websites, but there are concerns that, as they grow in stature, they could potentially be used by governments in warfare

Words: Edwin Smith

On 21st October 2016 the biggest cyber-attack of its kind began, bringing down huge swathes of the internet. Netflix, Twitter, Reddit, CNN and The Guardian were among the blue-chip sites to go offline when Dyn, a massive digital infrastructure company that routes much of the web’s traffic to its destination, was overwhelmed by a hugely powerful distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack that was twice as big as any seen to date.

DDoS attacks are nothing new. The technique is to flood a system with artificial or superfluous requests from multiple IP addresses, meaning that it lacks the capacity to deal with legitimate users. Imagine someone teaming up with their friends to order pizza to one address from every pizza place in London, blocking off traffic to their house and the whole street in the process. Such attacks have been used by hackers to exact revenge, earn money from extortion and make political statements on many occasions. But this latest example was different.

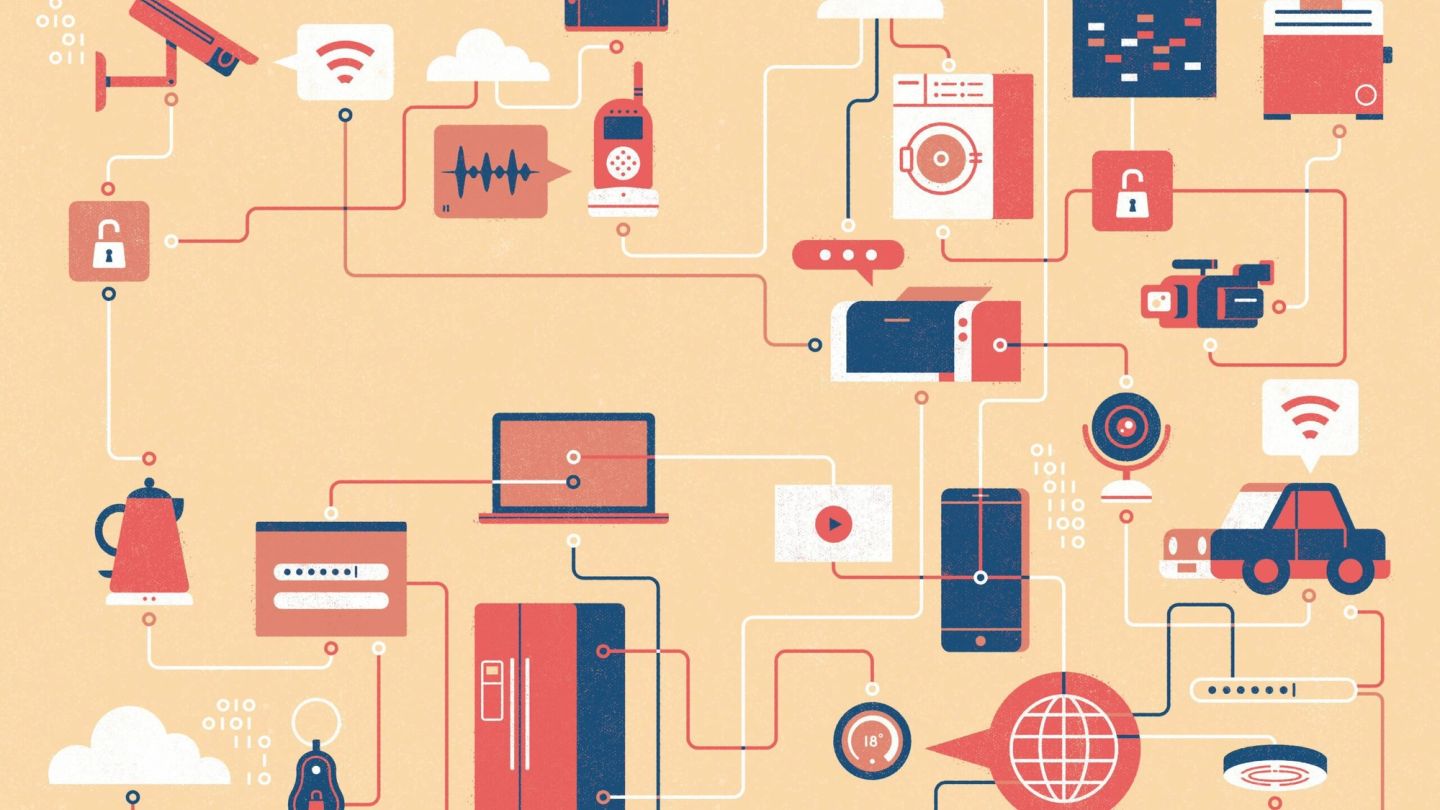

That’s because rather than using the IP addresses of other computers to launch the attack, the shady forces behind the assault on Dyn used other, smaller, simpler devices – devices that make up what we have come to know as the ‘Internet of Things’.

Representatives from Dyn and others in the industry now believe that the attack was carried out using the Mirai botnet – a tool that uses a type of malware to exploit components within devices such as internet-connected printers, security cameras, video recorders and baby monitors – before instructing the devices to overwhelm a chosen target.

Despite its huge size and power, the consequences of the attack weren’t very severe. Dyn says its operations were back to normal by the end of the day and, while it might have been expensive and annoying for the companies affected, there are no reports of serious, real-world disruption. No credit card details were stolen, no planes fell out of the sky.

But that hasn’t stopped the attack from ringing alarm bells, for several reasons. The first: it shows what could happen in the future. There are 6.4 billion connected devices in the world, according to tech consultancy firm Gartner. That figure represents a 30 per cent increase on the previous year, but it will be dwarfed by 2020, when nearly 20 billion such devices are expected to be in existence. By then, there will be many more connected devices like refrigerators, smoke detectors, toasters, thermostats, key rings etc, so there will be billions more viable targets.

The recent DDoS attack was testing the core defensive capabilities of the companies that provide critical internet services

The second cause for concern is the widespread feeling within the cybersecurity community that the Dyn attack and recent others of its ilk were merely test-runs – perhaps for something much larger.

In September, before the DDoS attack on Dyn, security expert Bruce Schneier had been prompted by a spate of similar, smaller events to take to his influential blog to say that ‘someone is testing the core defensive capabilities of the companies that provide critical internet services.’

Schneier’s reading of the situation is not unique. British cybersecurity expert Jamie Woodruff also told me after the Dyn attack that he believes ‘a massive attack is imminent’. But Schneier, who has authored several books on cybersecurity and holds the role of chief technology officer at IBM-owned Resilient, also speculated about who might be behind such activity. ‘It doesn’t seem like something an activist, criminal, or researcher would do,’ he wrote. ‘Profiling core infrastructure is common practice in espionage and intelligence gathering. It’s not normal for companies to do that. Furthermore, the size and scale of these probes points to state actors. It feels like a nation’s military cybercommand trying to calibrate its weaponry in the case of cyberwar.’

Schneieir is not convinced that the Dyn attack was the work of a state actor, but when I contact him, he explains that it would be possible for a tool such as the Mirai botnet to be wielded in a war – ‘not a fake war, but actual armies killing each other war.’ Schneier says: ‘A botnet could be used in much the same way as strategic bombing: to disrupt the home front. By taking critical infrastructure offline, one country could disrupt the other.’

A third reason to be fearful is that the power of the Mirai botnet now appears to be available to almost anyone. The party who was in control of the technology recently made the source code freely available online, but even for those without the expertise to wield it, there is also now the option to ‘rent’ a Mirai botnet reportedly made up of 400,000 devices. Hackers who are known by the pseudonyms BestBuy and Popopret are now offering punters the chance to hire it. Having presumably used the source code to create their own Mirai botnet, they sent out messages in November last year advertising the tool and quoting the price of a one-hour long attack using 50,000 bots at around $3,500.

The likely explanation for the decision of the Mirai botnet’s originator to offer the source code up for free is that they hope it will help them avoid capture or prosecution by the authorities. If several people are in possession of it, then merely having the Mirai source code is not, in itself, evidence of wrongdoing. However, the chances of a competent cyber criminal being caught and prosecuted are small.

There won’t be a cyberpanacea soon. It’s an arms race and it won’t be long before this technology is used on the attack side too

Sometimes the crooks make mistakes. For example, it looks as though allowing his real identity to be connected to an email address used to administer another DDoS attack may have been the undoing of alleged cybercriminal Yarden Bidani. The 18-year-old Isreali was arrested in connection with an FBI investigation in September along with another man of the same age, thought to be his associate, Itay Huri.

But it seems that carelessness on the part of the perpetrators of cybercrime is the authorities’ best hope of catching them. Using the dark web browser Tor, users can avoid detection of their behaviour online. The system – whose acronym comes from its full name, The Onion Router – applies layers of encryption to users’ data (including their IP address) and sends it to its eventual destination via several other computers or nodes which have become part of the network.

And, when you are about to collect money for all your criminal enterprises, it’s simple to use the cryptocurrency Bitcoin and an anonymous digital wallet to take an easily laundered payment. Another thing making cybercriminals’ lives easy is that many IoT devices are so simple to exploit. Independent cybersecurity reporter Brian Krebs – whose own website was the subject of a huge Mirai botnet attack – notes that a Chinese manufacturer XiongMai Technologies has used default usernames and passwords for many of its components that are built into other brands’ IoT products. What’s more, business risk intelligence firm Flashpoint says a scan of the internet for systems using the insecure XiongMai hardware revealed more than 515,000 that were vulnerable.

One solution to this problem might be to institute a quality seal for IoT technology that is protected by robust security – sort of like a Kitemark for tech. This is something the European Commission announced it is looking into, but even if it proves successful, the vulnerable devices in circulation are likely to cause concerns for some time to come. And, of course, the problems of cybersecurity don’t end with the Mirai botnet.

Ransomware is fast-growing,’ says Jamie Bartlett, author of The Dark Net and director of the Centre for Analysis of Social Media at the think-tank Demos. ‘You click on malware accidentally through an email you’ve received and it encrypts your hard drive. To decrypt it you need to pay a ransom, usually in Bitcoin to an anonymous wallet, so it’s hard to trace. There are thousands of cases of it happening.’

Although there’s nothing to force the criminals behind ransomware attacks to unlock a device once they’ve received payment, Bartlett says that they normally do – after all, their business model relies on people having confidence that it’s worth making the payment.

Dr Mary Aiken, author of The Cyber Effect, says that anonymity and ‘online disinhibition’ mean that many people ‘may do things in a cybercontext that they would not do otherwise’. This, combined with critical information such as bank details being stored on portable devices means that ‘we are moving towards a state of being high-risk victims, all the time’.

Dr Aiken, who works as an academic advisor to Europol’s Cyber Crime Centre, adds that: ‘We are seeing the evolution of “crime as a service” online. Some in law enforcement argue that we are facing a tsunami of criminality coming at us down the line.’ Bartlett adds that it’s not uncommon for large companies of all kinds, including hospitals and police forces, to stockpile Bitcoin in case they fall victim. ‘You can just go online and buy some ransomware software with thousands of stolen email addresses and simply do a mailout. So you could become a ransomware criminal without doing much at all. You just harvest the Bitcoin.’

But there are skilled operations, too. Bartlett mentions the recent TalkTalk attack, when personal details of 150,000 of the UK telecoms firm’s customers were hacked, as an example of a more sophisticated undertaking, likely planned in detail and carried out in an organised fashion. ‘They would have a market site set up to start selling the [stolen data]. A UK business can get attacked from anywhere – Russia, Ukraine, anywhere – and they’ll use all sorts of proxies, VPNs, or Tor browsers. So it’s hard to locate where an attack is coming from.’

Bartlett points to ‘penetration testing’ as a good form of defence. The idea is for security experts to be hired to probe an organisation’s physical and digital defences for weakness. If successful, other safeguards can be added. Brit Jamie Woodruff, mentioned earlier, is one such certified professional and often uses ‘social engineering’ techniques to find a way in. He told me recently how even the most modern security can be undone by people’s lax attitude to property and passwords. During a conference presentation in Norway, he remotely started the conference organiser’s well-protected Tesla car after gaining access to his personal information via his laptop.

Cybercrime cost the global economy a staggering $445 billion last year, according to a report from the World Economic Forum. But if it is causing a headache for companies and individuals at the moment, then it has also created opportunities. In 2003, the (legitimate) global cybersecurity industry was worth $3.5 billion, but now stands at $122 billion according to a report published by Markets and Markets.

As you would expect, the US is leading the charge, but there is also a burgeoning cybersecurity hub in Israel and another here, in the UK. ‘We are one of the best places for cybersecurity,’ says Emily Orton, one of the founders of Cambridge-based firm Darktrace. ‘We’ve got a strong set of capabilities in the UK – some of the best technical talent. We recruit from the university for [expertise in] machine learning. We’ve got a world-class team.’

While Orton admits that ‘compared to the US, we don’t have the same ecosystem’ for investment and funding, she stresses that the government’s recent announcement of £1.9 billion to be spent over five years, including investment in the National Cyber Security Centre, augurs well for the future. As does the progress made by Darktrace, whose products are already being used in 1,500 sites across 20 countries, despite only being founded in 2013.

The latest technology developed by the company, the Enterprise Immune System, is designed to mimic the way the human body wards off disease. It is part of a new wave of cybersecurity defence systems that use modern Artificial Intelligence and machine learning to offer protection from threats.

But, Orton warns, for all the excitement, there won’t be a cyberpanacea soon. ‘It’s an arms race,’ she says. ‘It won’t be long before this technology is used on the attack side too.’