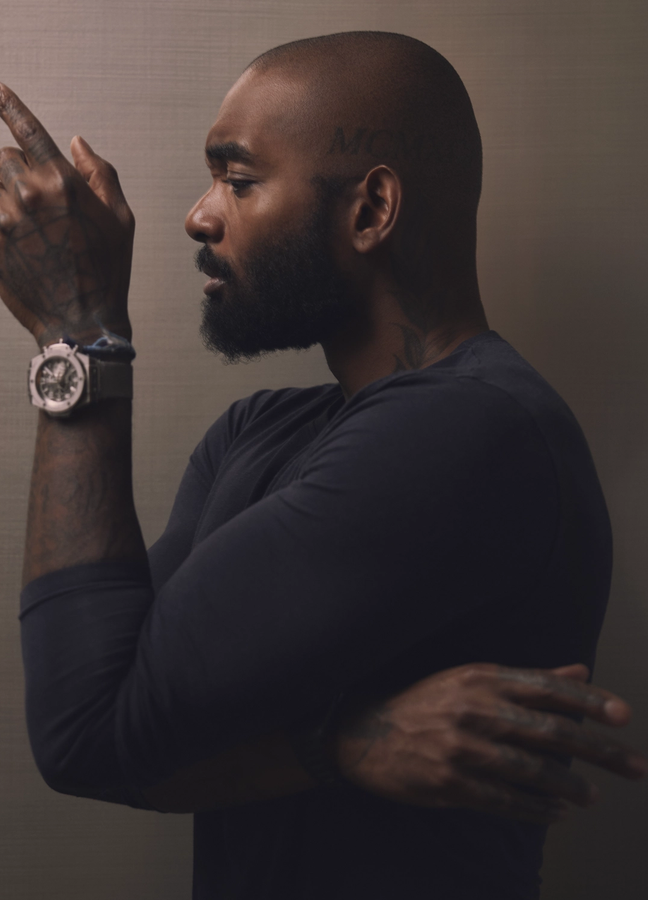

“Fashion allows you to portray into the future…” — Samuel Ross

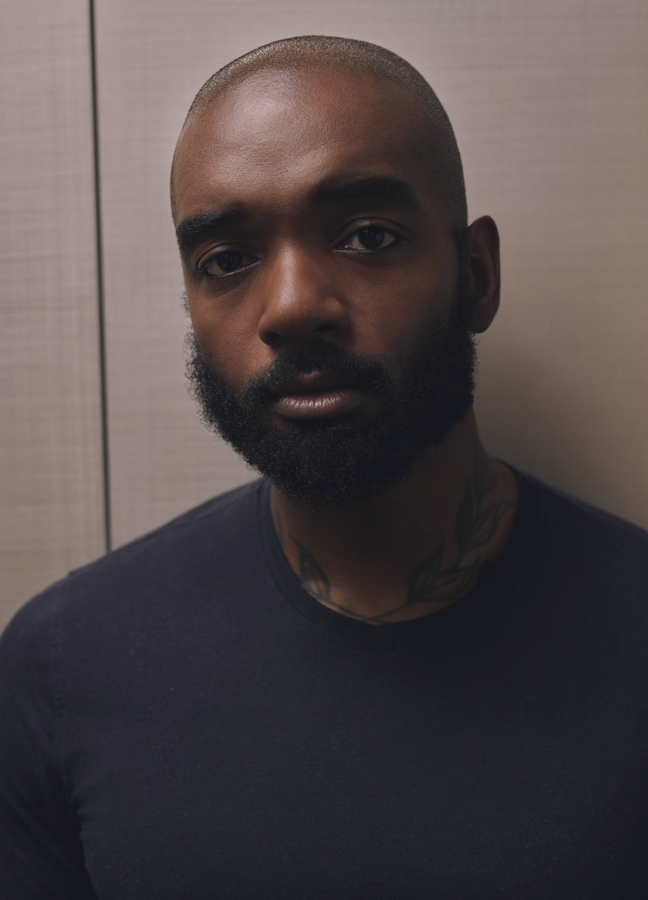

Samuel Ross MBE, designer and creative director

- Words: Jason Okundaye

- Photography: Barney Curran

Samuel Ross asserts to me that “there’s no other social tool that is as democratic as fashion”. It is a curious declaration for someone in the luxury space to make, considering high fashion’s association with heavy price tags and baked-in exclusivity. But for the polymath designer and artist, fashion is viewed as a means by which “people see you beyond your immediate circumstance. It’s almost like you’re able to portray into the future.”

When Ross was a university student, he wrote his final dissertation on “the power of the two-to-three piece suit in the midst of the Civil rights movement, pertaining in particular to the Nation of Islam and Malcolm X.” He speaks about how those vying for change, whether personal or systemic, have used fashion to “tap into ancient cues and monikers within an instance.” It’s less about signalling expense, but more about clothing as a way to communicate and, particularly in a British context, how we might move through different class systems. “That’s what’s liberating and freeing in the remit of clothing” he says, “the effigy of the suit, or the effigy of the tracksuit… you present yourself to the world, free of judgement. Or for judgement.”

We’re reflecting on social class and aspiration through fashion because two nights before we met at the Peninsula Residences in London, Ross had been watching a four-part documentary from 1998 on the Windrush generation, available on BBC iPlayer. He lives in Northamptonshire with his wife and two daughters, close to where he was raised as a child by his Caribbean parents, both educators, following stints in St Vincent and Barbados. He talks about his grandparents who would have been part of the cohort he watched in the documentary. “That generation, the matriarchs and patriarchs came as… if I were to put them into a political class, the majority would be liberal capitalists, who have a relatively conservative perspective on the world. That’s why they came to England dressed in suits, head to toe, to pick up a vocation, to accrue profits, to either stay or go back home.”

“I see tailoring and suiting as what it is, which is great performance.”

That’s just one of the political reflections Ross makes during our conversation, which is regularly inflected with observations about business and capital and government and ideology. Thinking about the world through a precise economic framework is something which was entrenched through his upbringing. He considers himself more of a “centrist,” but his father was a self-described “anarchist”, or, to Ross, a“socialist” who worked as a stain glass procurer restoring church windows. “He doesn’t have any interest in fiscal returns or growth or bonds or gilts. That’s not where his mind is.” Ross and his father would bond over building pinhole cameras from scratch, and when he felt that he might pursue computing or engineering, they would build computers together and attend computer fairs. “We would discuss broader ideas of politics, belonging, race and religion. He’s a seminal pillar in my life.”

Though raised in a left-wing family, he feels that his childhood pushed him to pursue profit. He says that the virtues of a childhood spent between Britain and the Caribbean were “fantastic”, but that he lived in relative poverty, and so made decisions to “ease fiscal difficulties within the household.” That was the main impetus behind going down the route of design — something with a clear vocational pathway rather than something more discipline-focused, like fine arts. It’s also why his practice has extended across fashion, industrial design, production design, and art, amongst other areas. “There’s always been this aversion to having complete commitment to one particular discipline, which is probably rooted in a fear of poverty.”

Ross, 34, was initiated into the industry with perhaps one of the rarest starting positions: age 20, he was the late Virgil Abloh’s first ever intern, working on the brand which would become Off-White. “It began very formally. He needed a design assistant, and I was able to get his attention..” Abloh had been appointed the creative director of Kanye West’s DONDA album, and brought Ross on board. “We started working 24/7. Kanye’s a pariah now, which makes it strange, but he was a massive part of it. Without a macro superstar you don’t have a benefactor for the Black arts. That was our Medici family and that period enabled these Black, diasporic, third-wave culture perspectives to exist and to become commercial and to turn profits.”

Three-and-a-half years later, Ross left to set up luxury sportswear brand A-COLD-WALL*, because he wanted to create something specific to his reality. “I could see there was a really clear African American narrative being told in apparel and culture and sport, but there wasn't a parallel in the UK. All I could fundamentally go off was what I could see from my childhood bedroom window, and that became the palette and the shapes and the forms and the references for ACW.” That vision for the label clearly resonated widely — it became an incredible success. He won awards — including the Hublot Design Prize and the British Fashion Award for Emerging Menswear Designer — and scored coveted collaborations with Nike and Oakley, as well as features in permanent museum collections in the Victoria & Albert Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and an MBE for services to fashion. In 2019, he founded SR_A SR_A, the industrial design studio, which his website describes as “an ongoing exploration into the artisan-driven, industrial beautification of precious garments, objects and space.” Largely, it was his answer to pricing models and overproduction that he felt was endemic in the luxury sector. In 2023, he would sell his majority stake in ACW and exit as Chair of the Board.

In 2020, Ross launched the Black British Artists Grant for Black British artists and other artists of colour. After engineering A-COLD-WALL* as a profitable company “which was built off the back of the cadences of modern society… the right thing to do was to make sure there was a silo of remuneration, back to the people that saw the narrative.” He asserts, though, that this is less about reciprocity, and more about ensuring that resources are “equally dispersed where possible.” After the first year of the profits being taken from ACW to fund BBAG, he decided to move it over to SR_A, which is completely independent. “We’ve continued to fund the same amount since then, and we’ve brought on partners such as Apple and Sotheby’s to assist with expanding the pool of finances.”

One inspiration for the Black British Artists Grant had been the British black arts movement of the 1980s, which artists such as Lubaina Himid, Sonia Boyce and Donald Rodney came through, and Ross’s feeling that often these movements and figures hadn’t been “afforded the documenting to be respected historically”. As such, he “wanted to build a directory so that people could see the participants of the liberal arts or applied arts sector.” And so the list of those who have come through the artists grant reads like a first draft for a new generation of greatness. The artist Rhea Dillon, whose 2023 show at the Tate Britain was assisted by the grant; Nifemi Marcus-Bello, whose works have been acquired by the Design Museum in London the Museum of Modern Art in New York amongst others; the Nottingham-based sculptor and designer Mac Collins. “We were able to disperse some funding, which led to Mac being included and winning the Ralph Saltzman design prize at the Design Museum,” Ross says.

But it’s not only the conventional artists and creatives who have been funded through the grant. Ross gushes about a gentleman named Rizzy. “We don’t even know his government name! But he’s based in Leyton and ran a barbershop for years, and we helped him with funding.” The idea, then — and a benefit of delivering grants through private capital rather than government — is that beneficiaries can participate without the strings and checks to assess the “worthiness” of subsidiary funding. “If we believed in the individual, or the cause underpinning what the individual is producing, we would fund it. Which meant that, as soon as the shortlist came about, I would sit on my laptop and just transfer all the funds. There's no third party in between.”

As we speak, I pause to remark on Ross’s footwear — a magnificent tan pair of trainers, and he tells me that they’re from his first SR_A collaboration with Zara, which debuted last year. He talks me through the design, “Japanese vegetable-tanned leather, small debossing throughout. Obviously, you’ve got the classic asymmetric and architectural designs and lines that I’ve been developing for years.”

Season two of the collection with Zara was released this October — and for Ross this relationship is one way he’s hoping to allow others to use fashion as a means for social mobility. “We can take the finest materials and democratise the price without sacrificing any of the detailing.” That exemplifies the range in Ross’s practice and reach — there are the watches he’s released which Hublot, which he says can retail at £430,000 and then there are the ventures with Inditex, Zara’s parent company, which help him “propose a vision for the future where taste and sensibility and quality of make comes before the price.”

Part of that diversification is also linked to what Ross portends as “the collapse of the discretional luxury sector,” which he feels has accelerated in the past four years. (Forecasts have indeed been difficult, but no one can fortune-tell and LVMH has recently announced a return to growth). He says that the sale of ACW was in part engineered because he “could see that the future wasn’t going to be about discretional goods being inflated without having a deeply grounded and functional use in society. When an economy is down and inflation is high, you have to be a lot more considerate with what the world actually needs.” It’s why he’s always been such a passionate advocate of sports and leisurewear — and indeed, alongside his excellent trainers, he’s also sporting a handsome melange grey tracksuit (though his wife tells him he “looks like he’s in HMP”). “There are intergenerational stories to be told around basketball or football or leisure, because they have a deeper root and tenant to the human experience.”

“When an economy is down and inflation is high, you have to be a lot more considerate with what the world actually needs.”

What reverberates across Ross’s work and his own personal consumption is a deep appreciation for craft. In his home and studio in Northamptonshire there are Benin bronzes and other West African sculptures which he’s been collecting for years. There are also antique church pews which he sourced from Lincolnshire, Bedfordshire and Northamptonshire, which he says “the British have discarded… these amazing crafted pieces of folk art.” That taste and interest in form and technique of course influences where he buys his clothes. He frequents Drake’s on Savile Row, noting “deconstructed twill tailoring” he gets from there, and he has a specialist tailor who simply refers to as “Peter” in North London who makes clothes for him. Like his Caribbean forebearers who suited up in pursuit of mobility, Ross says plainly: “I see tailoring and suiting as what it is, which is great performance.” On the other end are the tracksuits and sportier apparel, which is where he “feels the most at peace and the most comfortable.”

What’s next for Ross? A core focus on “democratic clothing” over discretional luxury, on direct-to-consumer business through SR_A, and continuing the Black British Artists Grant, which will soon announce its sixth round of funding. There’s a clear utilitarian principle that motivates Ross’s work — the idea of true access to all things for all people. “I’d like to ensure the nature of the programme doesn’t become too highbrow. I want to go into local communities and fund sports teams or provide funding for higher education opportunities. At times you have to disperse the funds as an act, rather than just waiting for people to come to you.”

Subscribe to Gentleman's Journal now to receive this issue to your door.