“Leave the gun, take the cannoli”: the life lessons we can learn from The Godfather

With the colder months drawing in, now's the time to set up camp in front of the TV. With this in mind, we look at one of cinema's finest works and examine what we can truly take away from the seminal masterpiece

Words: Josh Lee

Watch The Godfather – the exalted cinematic handiwork of Francis Ford Coppola – and you’ll enjoy three hours of the dark, clandestine workings of New York’s postwar underworld; the slack movements of Don Vito Corleone’s bulldog jaw; and what is widely accepted as the most referenced and layered dialogue in the past 50-or-so years of filmmaking.

There are virtuous quips by the shovel-load and enough gunshot wounds to make even the most ardent Second Amendment advocate think twice. Coppola – and his crew – sure knew how to elevate Mario Puzo’s novel of the same name to even loftier heights via the magic of the big screen.

However, despite all its measured and masterful pace; unforgiving violence; and nostalgia-tinged score, for steadfast loyalists, The Godfather is, in its pared-back essence, simply a philosophical musing, a story about America – its politics, its complications, its proverbial dream – and an incubator in which larger-than-life themes, such as justice, betrayal, loyalty, family and tradition, are explored.

Yet, with the script’s hackneyed quotes – “I’m gonna make him an offer he can't refuse” – forever pervasive and incessantly rehashed, and thus chipping away at the authenticity of the more profound messages, it is often a hard task to infer Coppola’s meaning within.

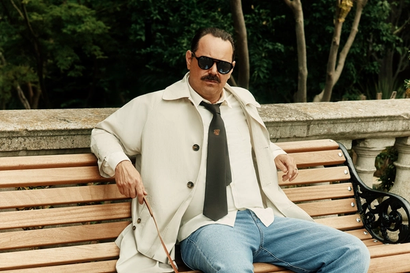

Indeed, with the wedding reception – the iconic set-play opener whose highlights reel includes Clemenza, the fridge-shaped caporegime to the Corleones, slugging a pitcher of red wine, dancing to the beat of his own rhythm, hair ruffled, top button undone; gabagool flying; and thousands of dollars in small bills being slipped into the silk bridal purse – we could perhaps argue that The Godfather is a blueprint of inspiration, however basic, for us to give into the freewheeling, debaucherous pleasures of life.

Tom Hagen, the family’s head lawyer and entrusted consigliere, is diligence and loyalty made flesh; and although his advice that the family should consider setting foot in the narcotics trade – “[it] is a thing of the future” – very much veered into the illegal, it sure demonstrated the virtues of forward-planning, if anything.

There were also those one-liners that have now become cliché – “A man who doesn’t spend time with his family can never be a real man” – and there were those one-liners that should be taken with the utmost regard: “Don’t forget the cannoli.”

Clemenza’s search for eighteen clean mattresses certainly extolled the benefits of a decent rest; Jack Woltz, the film producer who awoke to find the bloodied head of Khartoum, his $600,000 trophy horse, perhaps alludes to the notion of not flaunting your prized possessions too wildly; and Fredo’s fading hairline is, with absolute certainty, an allegory about how man should always give in to nature.

Then there are the oranges, the fruit whose nobbly fissures and rough-skinned peel encase juicy, sweet segments; the fruit that has come to be a popular symbol of fertility, longevity and sunshine.

Yet, throughout The Godfather, they pose as a signal of death. There are oranges that are stacked into a centrepiece during Woltz and Hagen’s business dinner, the evening prior to Khartoum’s ill-fate; there are oranges that are streaked across the street as Vito Corleone is gunned down at the market; and there are oranges that the don cuts up, seconds before his fatal heart attack. Was this Coppola’s message – that the fruits of your labour can be delightful and deadly in equal parts? Perhaps.

But it is probably suffice to say that the way in which Coppola artfully juxtaposed scenes – moving from a shot of an apprehensive back-office dealing to an innocent glimpse at Al Pacino’s Michael Christmas shopping with his long-term partner, before fading to Luca Brasi, Vito’s gun-for-hire in size 16 shoes, layering himself in a bullet-proof vest – was the ultimate commentary on life, and how it can dwindle between ugly contrasts and beautiful contradictions.

Life is, after all, a patchwork – brief lessons, simple and profound, pieced together both seamlessly and raggedly into a single, complicated whole.

If you so dare to read deeply between the lines, perhaps that was Coppola’s ultimate message.

Want more content from The Godfather? Step inside one of the film’s most iconic locations…