Life after politics: the second act

In light of yesterday's election, what happens when a politician's time on the podium is up?

On a balcony in the Hollywood hills, overlooking the darkened sprawl of greater Los Angeles, Sylvester Stallone is standing with two lycra-clad, silver-painted dancers from the Cirque du Soleil. In their arms, outstretched like a prize-winning catfish from a Louisiana bayou, lies blonde starlet Kate Hudson, dressed in a black lace shirt.

Nearby, at the same event, millionaire celebrity agent Michael Kives (the common denominator in this cornucopic guestlist) is brokering a deal with the help of some vintage Krug. Stage left, rock star Mick Jagger is jutting away in the shadows. And in the foreground, supporting Hudson’s head, is the former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland – a terracotta-tanned and wolfishly grinning man by the name of Tony Blair. If you want to know what life after politics looks like in 2016, this ought to furnish you with some clues.

If you want to know what life after politics looks like in 2016, this ought to furnish you with some clue

Hudson’s photograph of the tableau went viral on the 26th September this year. It could scarcely have arrived at a more poignant moment. Precisely two weeks earlier, David Cameron – who’d been languishing in the cracked leather of the back benches since his unexpected Brexit defeat – announced that he’d be giving up his West Oxfordshire seat and retiring from public life for good. The speech, given on a village green in Witney Parish, was casually formulaic stuff, down to the Polzeath-pink tan on Cameron’s upper slopes: I’ve thought long and hard; I support Teresa May; It’s been a great honour and a privilege; etc etc. And then: ‘But obviously I’m going to have to start to build a life [a pause, and that tiny lick of the lips] outside Westminster’.

In its various shades, ‘life after Westminster’ is the Ghost of Christmas Future that haunts politicians of every stripe

Within a few days Cameron was on a private flight to the USA – the land of the free, and of the filthy-rich ex-politician – to find out exactly what that pregnant phrase might mean. In its various shades, ‘life after Westminster’ is the Ghost of Christmas Future that haunts politicians of every stripe. It has visited Nick Clegg, the unceremoniously trounced former leader of the Liberal Democrats whose tell-all Politics: Between The Extremes came out just before the Hudson photo; it is playing hokey-cokey with Nigel Farage and his beloved UKIP; and it has long held an appointment with Barack Obama, when he hands over the keys of the Oval Office in January of next year. Twenty years ago, these men would have retreated to a pension, a book, a speech or two, and a genteel board position. There’s an old Enoch Powell quote (it’s one, in fact, that Cameron himself recited at his crucial moment of defeat) that says ‘all political lives end in failure’. Among the merry dance of circus acrobats, yacht-inflicted tans and movie star musclemen, things aren’t quite so clear cut any more.

Anna Gowthorpe/PA Wire

‘What Powell really should have said is “all ministerial careers end in tears”,’ says Edwina Currie. ‘At least, that’s what I’ve observed.’ Currie, who retired from politics after the 1997 General Election, is one of the few politicians of her generation to have built an enduring public persona beyond her political half-life. Hers has been secured by a varied career in entertainment, literature, and television, and her IMDB entry is a Who’s Who of prime-time reality TV: Strictly Come Dancing, I’m A Celebrity…, Celebrity Come Dine With Me. She also knows first-hand just how jarring the transition can be.

‘Front-bench politicians have been coasting along for several years on a sea of vanity. And now they are out in the real world, and it’s a very rude awakening.’ I ask her whether she thinks any politicians are adequately prepared for the shock. ‘There’s an assumption that you must have a pretty thick skin to suffer the slings and arrows of parliamentary life. I don’t think that’s the case. Afterwards, there’s anger, and depression, and anxiety.’

Needless to say, it helps to have a plan. ‘I started writing novels when I was an MP, in anticipation of losing my seat in 1992. Rather to my surprise, I held onto it. My books were due for release in ‘93 and ‘94, and they offered a slightly sexy view of government – I had never intended to be there when they came out.’ Of course, it’s easier to make a plan if you know what’s coming. (Currie tells a story of scandal-hit MP Hartley Booth popping his head around her door on the eve of the 1997 election and saying he’d been offered a £150k directorship in the City. ‘For christ’s sake, take it!’ she advised. ‘It was clear we were about to be hammered.’) It’s harder to manage if these things creep up on you, as they did on many unseated MPs in the horror-flick twists of the 2015 General Election.

In his new memoir, Balls speaks in disarming detail about that long night and the longer days that followed

In his new memoir Speaking Out, Balls speaks in disarming detail about that long night and the longer days that followed; of the mock eulogy that his staff gave for ‘the late Ed Balls’ over coupettes of Bristol Cream sherry; of the yawning, unexpected hours in the middle of the day. ‘For 20 years I’d had a whole office with everyone organising everything for me. Suddenly, I was on my own with an old Blackberry,’ he said recently, on a press call in his Strictly persona. ‘Booking cabs or trains? I didn’t know where to start.’ A few days after the election, Balls found himself in central London with a gap of a couple of hours between appointments. ‘I didn’t know what to do,’ he says. So he took the train home to Stoke Newington on London’s north-east edge, and then turned round and rode it back into town again. ‘I didn’t want to be photographed looking sad on a street corner,’ he says. There is a poignant moment in the book when his son walks in to find him sobbing in his study.

‘The greatest occupational hazard of politics is vanity,’ Edwina Currie explains. ‘It makes you forget what life was like before, and leaves you bereft when things suddenly disappear. What gets people into politics is a desire to change something. What makes people stay in politics is their ego.’

That ego is also a very good way to get on television. ‘They want someone with a big head, and they want to see them humiliated,’ she says. Often the producers get just what they’re after (One thinks of former Respect Party MP George Galloway purring like a cat on Celebrity Big Brother in 2006; Currie mentions how her argument in the jungle with Playgirl Kendra Wilkinson became the highest trending Twitter topic for a week in 2014 – ‘big hugs all round for that’) but often they’re left disappointed. ‘One of the skills that politicians learn is to be on your guard the whole time.’ I ask Currie whether she thinks Ed Balls’ recent foray into the ballroom will hurt any of his more serious ambitions. ‘I’m not sure it will, any more. Perhaps anything that makes you look more human now is a pretty good gig.’ But it’s in the most lucrative gig of all that the post-political ego proves a much more serious stumbling block.

‘The best speakers are very self-effacing; entirely self-deprecating, despite the fact they’re spilling over with insight.’ Jeremy Lee is the founder and CEO of Jeremy Lee Associates (known as JLA), the UK’s foremost agency for keynote, motivational and after dinner speakers. As such, he’s one of the biggest employers of former politicians in the world – sometimes for eye-watering fees, often for a great deal less than you’d expect. When it comes to their talent, JLA deploys a mercenary grading system, like a credit score or a Common Entrance Latin exam. ‘AA for the best of the bunch, then A, then sliding through to E for the perhaps less well-known figures.’ Each band corresponds to a ballpark fee (over 25k at the top, less than 1k at the bottom.) Former Lib Dem leader Paddy Ashdown, for example, comes in at B, or ‘5-10k’, where he shares a berth with cricketer Graeme Swann and comedienne Ruby Wax. This is the level at which most of the former politicians on JLA’s books come to settle. But not all of them.

‘William Hague is the undisputed master,’ says Jeremy with genuine warmth. ‘He is witty, he is sweet.’ And the rewards of that double-A banding aren’t just financial. ‘If you ask me whether William’s second political career has been helped by his prowess on the speaking circuit, I would say it’s certainly not a coincidence.’ Across the pond, however, a 25k fee is a drop in the ocean.

It’s a weekday afternoon in the middle of September, and David Cameron is sitting down to lunch with Tom Kenyon-Slaney in a Manhattan restaurant. Kenyon-Slaney, a sparkling Old Etonian with a hair-trigger sensor for a good anecdote, is the CEO at the London Speaker Bureau, an advisory network that sits half an echelon above JLA, and operates with a certain globetrotting panache. Despite its name, the LSB it does its best work in New York and Washington D.C, where it encounters vigorous competition from the similarly-positioned Washington Speaker Bureau. It is a competition that has just been heartily stoked.

‘Every former British leader since John Major has gone with the Washington Speaker Bureau!’ Kenyon-Slaney exclaims. ‘They tend to just follow each other.’ Sure enough, back in Manhattan, Cameron had informed the CEO that he too would be joining the line of succession. ‘They nabbed him.’ he says in frustration. ‘We were pitching against them. He was very charming and polite, but it was clear he had one foot in the American camp.’ And what, exactly, does Kenyon-Slaney think the deciding factor was? ‘I believe he’d taken advice elsewhere. That’s what swung his decision.’ Then a pause. ‘He’d been speaking to Tony Blair.’

The faintly cartoonish figure of the erstwhile Labour Prime Minister has re-defined what it means to be a former premier. We could point to the £2.5m a year JP Morgan ‘advisory role’ taken at the height of the financial crisis; the personal wealth assessed by the Telegraph at some £70m; the consultancy work through Tony Blair Associates to Middle Eastern groups with names like PetroSaudi; the close friendship with Wendi Deng and husband Rupert Murdoch.

‘You couldn’t make it up,’ wrote a former member of New Labour’s inner cabal. ‘His actions would be strange even for the most dyed-in-the-wool capitalist ex-prime minister, but for a Labour one… he’s trashed the New Labour brand.’ Yet in the process he’s built up an eerily powerful one of his own. No wonder Cameron sought his advice.

It’s quite lonely for them, I suppose, being an ex-PM. So they have to speak to other leaders

‘It’s quite lonely for them, I suppose, being an ex-PM. So they have to speak to other leaders,’ says Kenyon-Slaney. ‘Blair can command up to $200,000 a go. So someone like Cameron comes over to the US and their eyes go on stalks.’

Perhaps Cameron wants a taste of his forebear’s celebrity; a shot at the Hollywood selfies and the investment banks. ‘In America, Blair is feted as a god,’ explains Kenyon-Slaney. ‘And it’s entirely because he supported Bush at a time of war. They consider him a true patriot.’ Whatever his reasoning, it will appear questionable, even to a partisan onlooker, that Cameron was happy to sit down with a member of his opposition party – a man with an infamously shadowy and opportunistic post-political career – and seek his heartfelt advice about ‘next steps’. Suddenly, that village green in North Oxfordshire feels a very long way away.

‘There is nothing more pathetic in life than a former president.’ So said John Quincy Adams, during, as it happens, one of the 17 years in Congress that followed his presidency. Certainly, there’s something faintly needy about the American habit of addressing all former leaders as ‘Mr. President’ for their remaining years. There’s equally something of the retirement home about the various hobbies that former presidents tend to publicly pick up: George W. Bush and his (deliberately?) abstract oil paintings; Gerald Ford and golf. (Most of them and golf, come to think of it.) And that’s before you consider the age at which these men step out of office: most in their late sixties, Reagan at 77 (an age, incidentally, that both Clinton and Trump would reach in office, should they go the full two terms).

But you can bet Barack Obama won’t go quietly into the twilight when he finally steps down at the start of next year at the age of 55

But you can bet Barack Obama won’t go quietly into the twilight when he finally steps down at the start of next year at the age of 55. Speculation about the current president’s next step is suitably rampant (and specific details are guarded like the nuclear codes): Obama holds a unique place in history as the first black president, was a distinguished law professor in a previous life, and maintains a distinctive activist streak. He also holds, by the reckoning of the industry professionals I spoke to, by far the highest earning potential of any departing premier in history.

A good step to reaching that potential would be to author another book. In the deal that has made him $15.6 million dollars for his previous three releases, Obama was contractually obliged to write ‘a non-fiction book, subject to be determined’ when he became president. He reached an agreement with publishers Random House to put the book on hold while in office – they may be readying their paperwork as we speak. Perhaps more fitting, though, for the mould-breaking premier would be the ownership of a sports team – ‘I have fantasised about being able to put together a team and how much fun that would be; I think it’d be terrific,’ Obama said, in an interview with GQ last year – or perhaps even of an entire sports league: ‘I cannot believe that the commissioner of football gets paid $44 million a year!’ Tom Kenyon-Slaney thinks even that would be small change compared to Obama’s potential on the advisory circuit. ‘He is the biggest fish imaginable,’ the London Speaker Bureau CEO drools. ‘I can’t even imagine how much he could charge to speak or advise, if he really wanted to.’ On this topic, however, the administration has been particularly silent. That might have something to do with one Hillary Clinton.

‘She is really disliked in the US, and the speaking deals are a large contributing factor. She seen now as part of the financial establishment.’ says Kenyon-Slaney. It’s not hard to see how that perception came about. Since 2001, Hillary Clinton and husband Bill have performed 729 paid speeches at an average of $210,795, for a total profit of $153 million. Some $7.7 million of that came from 39 speeches to Wall Street banks, including Goldman Sachs and UBS. This, next to her secrecy over her email servers, is the most oft-cited reason for the vehement distrust that surrounds the Secretary of State. And it might have lasting consequences for the nation. ‘Hillary Clinton came out of politics, went everywhere with the Clinton Foundation, spoke at all the Wall Street Banks… and then came back into politics.’ explains Kenyon-Slaney. ‘That is a strategic error. That wasn’t very shrewd. And that might be the thing that decides the election.’

You can see why Obama might want to steer clear. For the same reasons, he’ll probably give politics a wide berth from now on, too.

Mark Wilson/Getty Images

‘The person who’ll be really after the influence is Michelle Obama,’ says Kenyon-Slaney, citing the general consensus that Michelle is far more stateswoman-like than almost all of the presidential candidacy hopefuls who’ve stumbled and fallen over the past year. As for Barack, the one definitive nod he’s given has been to the charity sector, and his mentoring initiative My Brother’s Keeper. ‘We are in this for the long haul,’ Obama said last year. ‘This will remain a mission for me and for Michelle not just for the rest of my presidency, but for the rest of my life.’

Ah, the cry of ‘giving back’: much-spouted in post-political life, often only fleetingly acted upon. That charge could not be levelled at David Miliband, the former foreign secretary who stepped away from British politics after he was pipped to the Labour leadership by his younger brother Ed in 2010, and took up the mantle of CEO of the New York-based International Rescue Committee. When we speak, via a crackling line to his New York office, it’s easy to see why ‘he’s the most impressive politician most people have ever seen,’ as Kenyon-Slaney puts it. He’s charming, warm, magnanimous, slightly guarded.

‘In politics, everyone is trying to do you in every day’ he tells me. ‘But in the charity sector, everyone is generally on the same side. That’s one thing that eased the transition.’ Another was the shared purpose of both disciplines: ‘In both charity and public service, you’re driven by a commitment to social goals’ he says. ‘You’re trying to make the world better one life at a time.’ One wonders if Blair or Cameron can realistically claim that line.

Then we come to the elephant on the phone line: Does Miliband plan a return to politics? And how about a shot at the US game? (Kenyon-Slaney: ‘The rumour is that Hillary will give him a job – he’s seen as being very similar to her, politically.’) ‘I don’t think British citizens can expect to do too well in US politics,’ Miliband laughs. But when I ask him about a return to Westminster, especially in light of the cavalcade of Labour MPs who called in August for him to return and oust Jeremy Corbyn – he is tellingly vague. ‘I’m very much committed to my task at the moment. I’m just trying to take each stage of life as the adventure that it is,’ he says. ‘And it is an adventure.’

I don’t think British citizens can expect to do too well in US politics

If modern life after politics had a clubhouse, in fact, that would be the inscription above the door. It’s an adventure. ‘My advice to anyone leaving politics tomorrow is this,’ says Edwina Currie, the club grandee. ‘Say yes – you have all sorts of wild talents that have long been suppressed.’ A knack for the paso doble, perhaps, or an aptitude towards easing a migrant crisis, or a flair for viral Instagram poses, or a gift for converting influence into cash. This is no longer an epilogue, but the main act: watch closely, in the coming months, as these latest initiates take the stage.

This article in taken from our November/December issue. Subscribe to the magazine here.

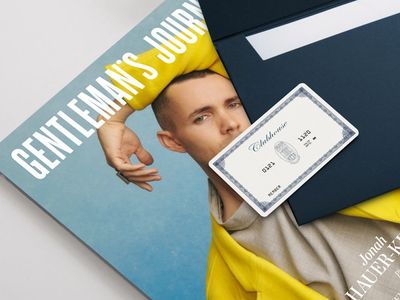

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.