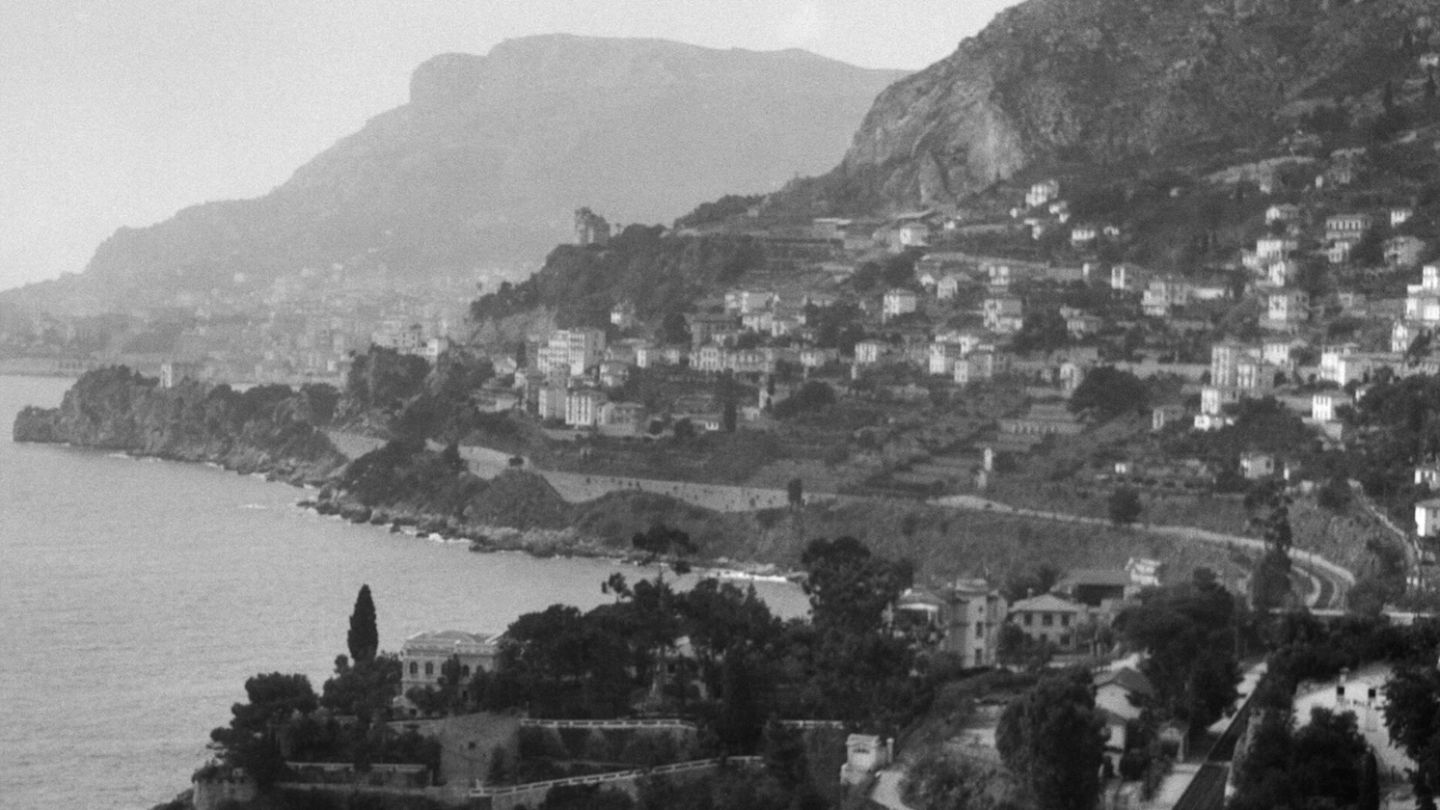

Charting the history of the Côte d’Azur, a playground for rich villains

In his new book Once Upon a Time World, Jonathan Miles looks at the French Riviera's past – with all its sheen and shadow – mining memoirs, novels and films to reveal the most delightful nuggets of gossip, debauchery and, ultimately, corruption

Words: Harry Shukman

“A sunny place for shady people” is how William Somerset Maugham famously described the French Riviera. A playground for rich villains to slurp bouillabaisse and chug champagne and share tips on circumventing arms-trade embargoes. Glitzy though it may be, the Riviera has always had a nasty edge: a scummy layer of chewing gum and saliva beneath the pressed white linen tablecloths. In the Patrick Melrose novels — which skewer the fading British aristocracy — the south-eastern French coast is a gilded circle of hell. One of the hero’s earliest childhood memories is watching his alcoholic grandfather on a bench outside the Monte Carlo casino, “shaking uncontrollably, clamped by sunlight, a stain spreading slowly through the pearl-grey trousers of his perfectly cut suit”. Anyone who has run the emetic gauntlet of a night out in Monaco’s Amber Lounge (cost of a table: €35,000) will find that description somewhat familiar.

For generations the Riviera has haunted and fascinated British writers, to the point that a traumatic childhood trip to the Côte d’Azur is almost a prerequisite for literary success. A young John Le Carré was obsessed by the “pigeon tunnel” at the hunting club in Monte Carlo, which trapped birds so that “well-lunched sporting gentlemen” could shoot them for sport. AA Gill called Monaco a “mangrove swamp of avarice”, totally lacking “taste and a sense of the collective good”. An unfortunate visit there, he wrote, is “deeply depressing, so comprehensively devoid of any amusement, expectation or glamour, so utterly tacky, witless, empty and sad”. The message has apparently not sunk in. Four hundred thousand tourists go to Monaco each year. And how many people visit the wider coastal region? Ten million.

Back in the early days, it was a little more exclusive. It began as a winter getaway for sick plutocrats in the early 19th century, but soon anyone who was anyone was coming to the Riviera to splash their hot little feet in the waters of, say, Cap d’Antibes and snooze off their fourth glass of lunchtime rosé in the shade of a pine tree. The historic guest list reads like Who’s Who: Summer Holiday Edition. Oscar Wilde, Picasso, Coco Chanel, James Baldwin, The Rolling Stones, Friedrich Nietzsche, Jean-Paul Sartre, most of Queen Victoria’s European relatives — not to mention the old monarch herself — plus Rita Hayworth, Karl Marx, Anton Chekhov, Noël Coward, Graham Greene, Aristotle Onassis. F Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald liked it a little too much – Zelda was barred from a hotel for trapping the lift on her floor with a belt, so she could descend to the restaurant without a moment’s delay, and husband Scott arrived at one dinner party late and hammered, burbling “this is how I want to live, this is how I want to live”, before passing out with his head on the linen.

So, what is it about this little corner of France — once home to a few sleepy fishing villages — that has captivated so many? That is what Jonathan Miles, author of the comprehensive Once Upon a Time World, has tried to find out. Charting the history of the Riviera, with all its sheen and shadow, he has mined the memoirs and novels and films that have emerged from the Côte d’Azur and returned with delightful nuggets of gossip. A gripping and at times dizzying read, it is like being driven in a Lotus Esprit at 90mph around the region’s hairpin bends by a tour guide excitedly pointing out local esoterica: this is the hotel swimming pool filled with cologne for Rita Hayworth’s 1949 marriage to Aly Khan; this is where Oscar Wilde was greeted by Queen Victoria’s son Edward; this is where Napoleon III’s widow — a known hater of flowers — slashed the blooms of Cap Martin with her walking stick. If you are heading to the south of France this summer, consider your poolside reading material sorted.

Perhaps the history of the Riviera would have been very different had Lord Brougham, designer of the horse-drawn carriage that bears his name, not shown up by chance in 1834. On his way to Genoa, Brougham was stranded in Cannes when the borders were shut because of a cholera epidemic. He fell in love with the place — the night sky, the beaches, the fish soup — so he purchased land and built a villa, encouraging his compatriots to visit and settle there, too. The rise of Cannes was soon underway. Before long, 25 English families were ensconced in their custom-made châteaux, playing tennis at the new Hotel Beau Site and pootling about the port that King Louis Philippe built at Lord Brougham’s behest. The English had arrived.

Visiting royals zhuzhed up the Riviera. Queen Victoria, travelling incognito as the Countess of Balmoral (“she did not deceive a soul,” lamented a French police officer tasked with protecting her), was an early fan. She travelled down by royal train — how discreet — and among the many fantastic and colourful details that Miles digs out are the late monarch’s dining habits. While her entourage tucked into French dishes, the queen ate Irish stew from Windsor. The royal dinner — which must have been prepared many days before crossing the Channel — was, says Miles, “kept lukewarm in red flannel pouches hung from the carriages, an unappetising practice that persisted on the queen’s subsequent visits to the south”. Yuck!

Famous visitors to the Côte d’Azur, including Oscar Wilde, Pablo Picasso, Jean-Paul Sartre, Zelda Fitzgerald and Queen Victoria

The construction of a train line to Nice and a casino at Monte Carlo began to draw in visitors rapidly. Opened in 1866 in time for the summer season, the casino transformed Monaco into the money-drenched circus it is today (where the average price per square metre of property, it should be noted, is now €51,000). This sleepy principality became a city of addicts, hooked on cards and roulette. Bien-pensant commentators bemoaned the opera audiences’ habit of slipping away between acts to hit the felt. Tourists today who have had the misfortune to visit Las Vegas and watch the loners thumping coins into the slot machines with nothing but a pack of cigarettes and a two-litre bottle of Coca-Cola for company may feel some sympathy for the bewildered fishermen of Monaco seeing their town’s metamorphosis in the mid 19th century.

Not long after the casino opened, the town became afflicted by debt-related suicides — a newspaper reported 19 deaths in three months from gamblers “ruined by play”. The casino started bribing the press to stop reporting on these tragedies. When gamblers ran out of luck on the tables and were unable to pay their debts, casino bosses had a system: they would bar them from returning after a humiliating ritual. Debtors would be photographed and marched round the casino, then shown to the bouncers so they would be spotted if they tried to come back. They would be bundled on to a train at the railway station — second class, the shame of it! — and hustled away. Dorothy Parker, some decades later, once joked about the casino’s odd fashion rules, describing how she was turned away for not wearing tights. “I went and found my stockings,” she quipped, “and then came back and lost my shirt.”

Just as disastrous for the fate of the Riviera was the arrival, in force, of the Brits. A load of red-faced holidaymakers started showing up, making nuisances of themselves, creating such hostilities with the local population that poor relations endure to this day. “Stiff, haughty, unbending behaviour” is how one 19th-century observer described our Riviera-visiting forefathers. “The majority of our travelling compatriots indulge in incessant depreciation of all the manners and institutions of foreign lands, or in invidious comparisons with something they think much better at home,” wailed one tourist at the time. English visitors sat on terraces, reading English newspapers, eating plain roast beef and boiled potatoes, and complaining about foreigners. “Very undesirable associates,” sniffed the Paris Herald. Unpleasantness aside, the Brits brought in money, and the royal glamour helped to market the Riviera as a chic holiday destination.

It seems counterintuitive, given how grotesque some late-19th-century royals were, that anyone was willing to copy their holidaying habits. Edward VII, son of Queen Victoria, was so fat that his favourite French brothel had to construct a special “love chair” so that he could have sex without crushing his partners. King Leopold II of Belgium, the tyrant whose Congolese colony became a byword for the violence of the imperial age, had sinisterly long fingernails and tucked his beard into a rubber pouch when swimming. Perhaps spotting a gap in the market, a Spanish courtesan set up shop in Monte Carlo under the name La Belle Otero — she later said that no queen had ever lived like her, because she had “been through so many kings”. King Alfonso XIII of Spain, the Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, Kaiser Wilhelm, Prince Albert I of Monaco — she bedded them all, and lived to the impressive age of 96, dying in Nice in 1965.

‘Côte-d’Azur all the year round’ poster

The funny thing about the Riviera is that for decades people have loved and hated it. Edward Lear, the poet, said “it is odious to me in all respects”, except for the weather. The Russian painter Marie Bashkirtse said it was “execrable”, and yet she spent all the time she could there. Anton Chekhov, the playwright, said there was “something hovering in the air that insults your decency” in the Côte d’Azur, but conceded that restaurants “feed you magnificently”.

I am surprised by Miles’s sympathy for two particular devils: the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. Many will be vaguely familiar with Edward VIII and Wallis Simpson as the Hitler-loving traitors, who in the 1930s and 40s conspired with the Third Reich against Britain. Exiled to the Bahamas and then the south of France, they lived out their days in luxury: cue an orchestra of the world’s smallest string instruments. Miles sees them as tragic figures, however, describing their relationship in our interview as the “love story of the century”. Moping out the rest of their lives in golden exile, Miles describes their 1937 visit to Nazi Germany as “ill-advised” — an understatement if there ever was one — and suggests the duke was not quite as full-throated in his support of Hitler as the history books make out. This stands a little at odds with reports describing the duke’s dislike of those belonging to a certain Abrahamic faith, and the telegrams he is said to have sent the Nazis, providing a layout of Buckingham Palace so it could be more accurately bombed.

Miles concedes in our interview that the duke was “not the firmest cookie in the packet”, and in his book focuses more on the Windsors as star-crossed lovers. True, much of the ire they received in the 1930s was due to Simpson’s relationship history — twice divorced — than her and her beloved’s Nazi sympathies. At the height of the abdication crisis, Simpson retreated to the South of France to allow things in England to die down, but had a miserable time of it. Queen Maud of Norway remarked that in Monte Carlo “all the English and French” left the room whenever Simpson walked in. Still, it is hard to feel too much sympathy for the couple. Joined by Edward after he abandoned the throne, they settled at a château at Cap d’Antibes, set on 12 acres of sea-front property (they had another pile at Versailles). Winston Churchill visited and after dinner remarked that Edward, now he was no longer king, missed royal protocol and “had to fight for his place in the conversation like other people”. Boohoo!

The Riviera has long been beset by wealthy malfeasants, but at some point after the war they began to show up in uncomfortable numbers, upsetting the ecosystem. Too many crooks spoil the broth, one might say. Miles is particularly upset by Lady (Norah) Docker, a former lampshade saleswoman from Derby who married the head of the Birmingham Small Arms Company and the chairman of Daimler. Norah boasted six gold-plated luxury vehicles, including one upholstered with zebra skin. Why zebra? “Mink is too hot to sit on,” she told an interviewer. Miles describes Norah to me as “the original tabloid whinger”, meaning she knew “how to handle the press, turning every bit of her life into a mega drama”. She went around slapping casino workers, and ultimately was banned from Monaco in 1958. “She’s pretty odious,” Miles concludes on our call.

“The historic guest list reads like who’s who: summer holiday edition. Oscar wilde, picasso, coco chanel, james baldwin, the rolling stones...”

Miles is fonder of James Gordon Bennett, a newspaperman in exile from the US after public urination, who in 1880 launched the Paris edition of the New York Herald. He was a fan of walking into restaurants and buying them. His behaviour doesn’t seem a great deal better than Lady Docker’s — if restaurant service was slow, Bennett would yank out tablecloths to send glass and china smashing on to the door, and he was fond of throwing rolls of money into open fires. Where does eccentricity end and cruelty begin?

Churchill, ever prescient, noted the Riviera’s creeping commercialism in the 1950s. Simone de Beauvoir joked that Brigitte Bardot, having starred in the St Tropez movie And God Created Woman, became “an export product as important as Renault automobiles”. Thus, the crowds began flocking to the coast. Nice Airport was built in 1945 and was soon serving a quarter of a million passengers a year. A development boom followed, and Dirk Bogarde sadly noticed from his house in Grasse that there was so much building work that the birds began to leave. “The party’s over now,” sang Noël Coward, and Graham Greene, protesting the rampant corruption that prevailed over the Côte d’Azur, quipped that it had become the “Côte d’Ordure”.

There are oligarchs who today feel right at home in this part of the world, but even before then the region has been home to some legendary criminals. Not least Jacques Médecin, the bigoted mayor of Nice, who was stopped at LAX with a suitcase full of jewels. He was done for tax dodging and embezzling public money — his house was raided, and a young associate was nabbed travelling through an airport with a suitcase labelled “Médecin” stuffed with 600,000 francs. Ça alors! Perhaps it says something about the region that one of Nice’s local heroes was Albert Spaggiari, a bank robber who in 1976 made off with 46 million francs after a sophisticated raid on a city bank.

Something happened in the late 20th century, and amid the development and deaths, some of the glamour and exclusivity of the Riviera began to wear off. “Gone were the ghosts of the Windsors, Aristotle Onassis and his brother-in-law, the shipping magnate Stavros Niarchos,” writes Miles. While a summer spent on the south coast sounds immeasurably more special then than it does now, I’m not convinced the Windsors, Onassis and Niarchos would have made the best of companions. Would you really want any of them round for dinner on your terrace? The dunce Windsors, fondly recalling their visit to Nazi Germany? Niarchos, implicated in the death of his third wife by barbiturate overdose, whose body was found covered in bruises? Onassis, describing his dodgy dealings with the Greek dictatorship? Compared to that lot, Norah Docker doesn’t sound so bad.

I’m keen to ask Miles if he thinks there is any charm left to the Riviera, or if it is all, as he describes St Tropez, “exorbitantly priced drinks”, “envy”, and “yachts more often than not registered in tax-free havens”.

Edvard Munch, At the Roulette Table in Monte Carlo, 1892

In his book, he writes that the magic is still there, rhapsodising about the off season: “Gentle breezes blow and light sparkles on the surface of translucent water that deepens into the 1,001 blues of a Côte d’Azur”. On our call, Miles says, however: “You’ve got to be very clever. It’s an overcrowded planet, and everywhere is suffering from Parthenon pollution, where monuments get worn down from too many visitors.”

There might be hidden gems here and there along the coast, but Monaco is probably beyond saving. “It is an odd place,” he says. “The Monégasques are really lovely. It’s a bit like being in Disneyland, you could eat breakfast off the pavement. The public loos are probably cleaner and better than the ones you find in a five-star hotel.” The Condamine market area still has its charms, but otherwise Queen Victoria’s assessment more than a century ago was accurate. “Monte Carlo is a very clean looking place,” she wrote, before a caveat for the ages: “One saw very nasty disreputable looking people walking about.”

This feature was taken from Gentleman’s Journal’s Summer 2023 issue. Read more about it here…

Want more long-reads? These are the high-end crisis managers who fix the unfixable…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal member. Find out more here.