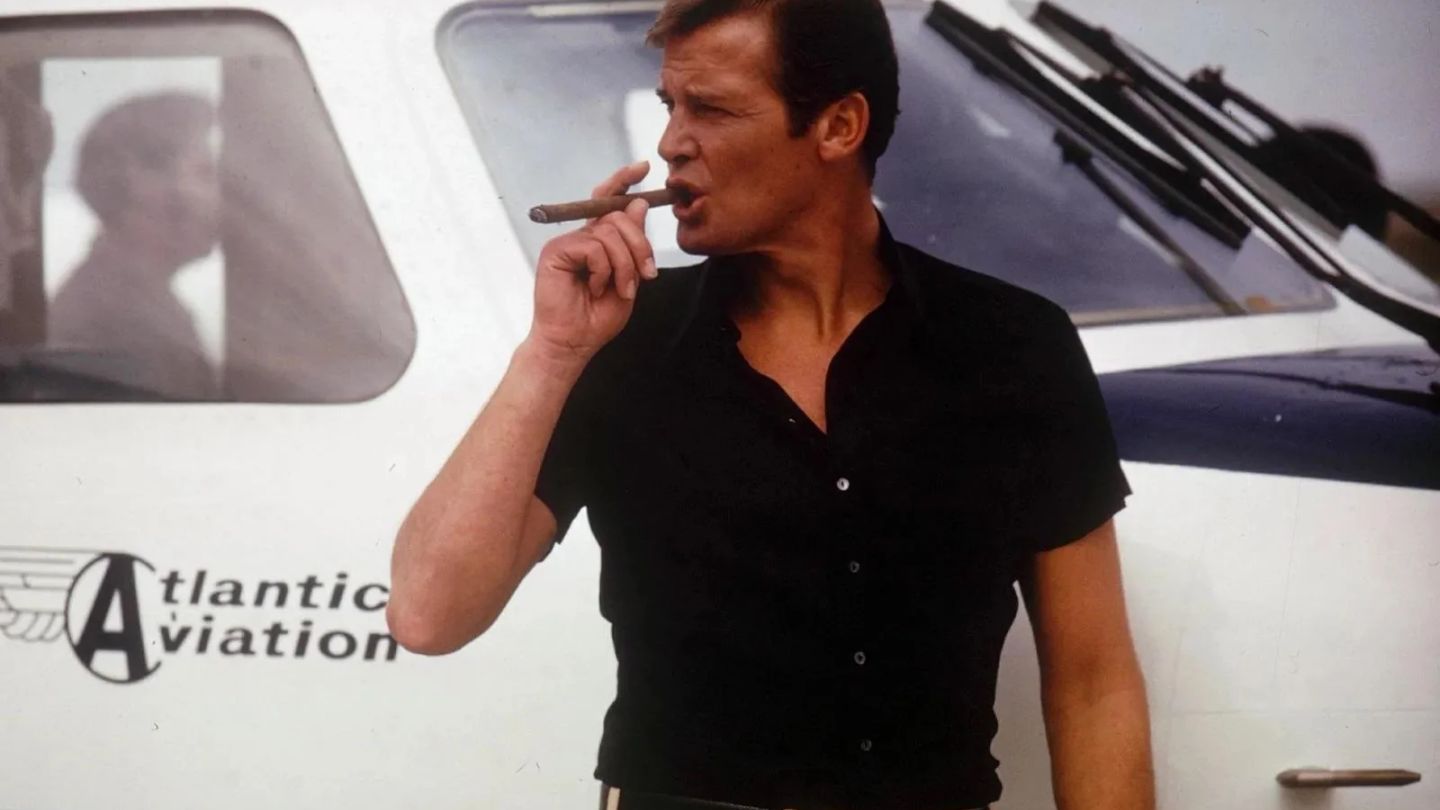

How to Light a Cigar Like a Seasoned Smoker

Knowing how to light a cigar is as much about respect as technique. The flame should kiss the leaf, not consume it, allowing the cigar to open slowly and reveal its character in time.

- Words: Rupert Taylor

The first thing one learns about cigars is that nobody truly needs to smoke them. They exist purely because civilisation invented spare time. Lighting one, then, is less an act of necessity than of ceremony, the closest thing most men will ever experience to conducting a small orchestra made entirely of smoke. A cigar is not a cigarette, nor is it a substitute for thought. It is an elaborate excuse to sit still and look contemplative.

And, like all things touched by ritual, the handshake, the necktie, the concept of brunch, it has acquired rules, etiquette, and a faint whiff of absurdity. Lighting a cigar badly will invite the same expression one earns by buttering a scone incorrectly in Pall Mall. Lighting it well, on the other hand, will win you silent approval from elderly men who have not smiled since 1987.

The Seasoned Smoker’s Mindset

Every good ritual begins with a delusion, and cigars are no exception. The seasoned smoker convinces himself that lighting one is a meditative act of taste and patience. In truth, it is a complex way to set something on fire without looking ridiculous.

Approach it with composure. You must appear unhurried, yet vaguely purposeful, like a man who has just remembered something clever but cannot be bothered to share it. The first rule is never to look as though you are trying to be a seasoned smoker. The second is to ensure you have the correct drink at your side. Whisky is acceptable, cognac better, water an abomination.

Once seated, and cigar smoking is very much a seated sport, you will feel the transformation begin. Conversation slows. Your posture improves. You acquire the sudden gravitas of a colonial governor pondering trade routes. This is normal.

Selecting the Cigar

Choosing a cigar is where the theatre begins. There will always be someone in the room who asks,

“What are you smoking?”

as though the answer will alter the Dow Jones. Say something authoritative but vague. “A Cohiba,” perhaps, or “Montecristo.” Never “whatever was in the box.”

The Cohiba is confident, all Havana sunshine and charm. The Montecristo is more introspective, a cigar for those who enjoy their pleasures quietly and their applause even quieter. A Romeo y Julieta, meanwhile, suits the romantic optimist who still believes good things happen in hotel bars.

When examining the cigar, look thoughtful but not intimate. You are not proposing to it. Run a finger along the wrapper, check the firmness, inhale the scent with restraint. The aroma should whisper of earth and cedar, never of desperation. Those who squeeze too hard or sniff too long invariably look as though they have confused the cigar lounge for a greengrocer’s stall.

In short, one must handle the cigar as one handles a Duchess’s dog, with respect, amusement, and the suspicion it might bite if provoked.

How To Light a Cigar with Intention

Now comes the business of fire, and with it, the opportunity to reveal one’s character. A cigar lighter says more about a man than his watch. Petrol lighters are for poets who cannot afford therapy. Matches are charming, provided they do not singe the wallpaper. Butane lighters, clean and odourless, are the modern standard, though one must avoid those industrial jet varieties that roar like fighter planes.

I once watched a man light a cigar with such enthusiasm that the flame singed his cuff. It was a deeply moving experience. The cigar, to its credit, survived.

If you wish to be traditional, use cedar spills. They burn beautifully, smell faintly of old wardrobes and self-control, and are available only in places that spell “colour” correctly. They also allow you to perform the small, dramatic flick that every cigar smoker secretly rehearses in the mirror.

Hold the cigar gently, bring the flame near, and begin to rotate the foot, that is, the open end, as though you are warming a spoon of something rare. Do not puff yet. This is called toasting, and it is where the experienced smoker makes his first impression. Those who rush this stage invariably produce a burn so uneven it looks like an avant-garde candle.

A proper toasting takes time. The aim is to coax the tobacco, not incinerate it. Think of yourself as a diplomat introducing two world leaders at a peace summit. No sudden movements.

The First Draw

At last, you may smoke. Bring the cigar to your lips and draw slowly, turning it so the flame licks the foot evenly. When it glows with a steady, calm orange light, you may lean back and pretend you have achieved something significant.

That first draw will tell you everything. The Cohiba greets you with warmth and spice. The Montecristo opens like a sonata. The Romeo y Julieta sighs romantically, then forgets why. In any case, you must look as though you expected this exact result. Surprise is vulgar.

Do not inhale. This is the fastest route to humiliation. Cigar smoke is meant to linger in the mouth, to roll like a well-delivered compliment. Inhale it and you will cough like a Soviet tractor. Allow the smoke to escape slowly, preferably through your nose, as though expressing mild disappointment in someone else’s decision.

The key to the draw is rhythm. Too frequent and the cigar burns hot, losing its nuance. Too slow and it goes out, sulking like an ignored spaniel. Aim for one draw a minute, the tempo of a man with nowhere urgent to be.

The Etiquette of the Flame

Every club has its own unspoken laws, and most revolve around not embarrassing oneself in front of the upholstery. Never light another man’s cigar unless he asks. Never puff theatrically. And never, under any circumstances, attempt to relight using a candle. The smell of paraffin mingled with pride is difficult to forget.

If your cigar dies, as they sometimes do, tap the ash gently, blow through the cigar once to clear stale smoke, and begin again with patience. There is no shame in this. What is shameful is the man who insists it is still lit and spends ten minutes puffing on an uncooperative husk.

A friend of mine insists he can tell a man’s entire moral character by how he handles a lighter. He says those who click nervously before each puff are doomed to indecision. I have seen no reason to disagree.

Lighting a Cigar in Company

Lighting a cigar among others is a study in manners. The act itself becomes a conversation, one conducted entirely in glances and nods. When offering your flame, hold it steady, allow the other man to guide his cigar, and withdraw gracefully. Do not lean in as though to inspect his progress. This is not a driving test.

In company, timing is everything. Lighting your cigar too early makes you appear overeager. Too late and you risk looking aloof. The secret is to wait until the first cloud of smoke has risen from someone else’s corner, then proceed as if reminded of your own existence.

There is something wonderfully absurd about a group of men performing this choreography, each pretending not to care while secretly competing for the most elegant plume. It is the male equivalent of synchronised swimming.

The Setting for the Seasoned Smoker

Cigars do not belong outdoors, except perhaps on a veranda where one can watch the rain fall on people with less comfortable hobbies. The ideal environment is indoors, where the air hangs with faint memory of oak and conversation.

Mayfair offers no shortage of suitable venues. There is always a club with leather armchairs, decanters, and the low growl of men discussing subjects of staggering unimportance. Here, lighting a cigar is as much a part of the decor as the portrait of some forgotten baronet glaring down in mild disapproval.

You may pair your cigar with a drink. Whisky is reliable. Cognac is noble. Rum, if one must. The combination, however, is not about intoxication. It is about symmetry. The spirit mirrors the smoke. Together they create that curious illusion of profundity that makes even the most trivial anecdote sound like diplomacy.

On Ash and Other Tragedies

A good cigar forms a long, straight ash that clings stubbornly, like an old friend who refuses to leave a party. Do not flick it off. Let gravity do the work. If it drops into your lap, pretend it was intentional.

A crooked burn suggests haste in lighting. You may correct it with a brief kiss of flame, but do not panic. Cigars, like British trains, rarely run perfectly on time.

The cigar should be smoked until it signals its own conclusion. When it grows too hot or sharp, lay it in the ashtray and let it fade. Crushing it out is unforgivable. One does not murder a guest. One simply allows the visit to end.

The Reflection

By the time the cigar has dwindled, you will notice a peculiar serenity. The ritual has done its work. The room appears softer, the conversation slower, the world briefly tolerable. This is the secret all seasoned smokers share, the knowledge that it is not the cigar itself that matters, but the calm it creates.

Lighting a cigar is, at heart, an exercise in futility performed beautifully. It achieves nothing and yet improves everything. It is the last refuge of the contemplative man, the one ritual left in an age allergic to waiting.

Each time I light a cigar, I remember an old member of White’s who told me, “The thing about cigars is that they give you an excuse to do nothing at all, and make it look cultivated.” I have found this to be among the few pieces of advice worth keeping.

So, when next you find yourself in Mayfair, surrounded by the soft murmur of evening, take a seat, select your cigar with the solemnity of a statesman, and light it with care. Rotate, toast, draw, and exhale. Then sit back, say nothing, and enjoy the quiet comedy of an ancient ritual performed by men who should know better, but mercifully never will.

Further reading

The Country Gear Guide