A Gentleman’s Guide to Dolce Far Niente

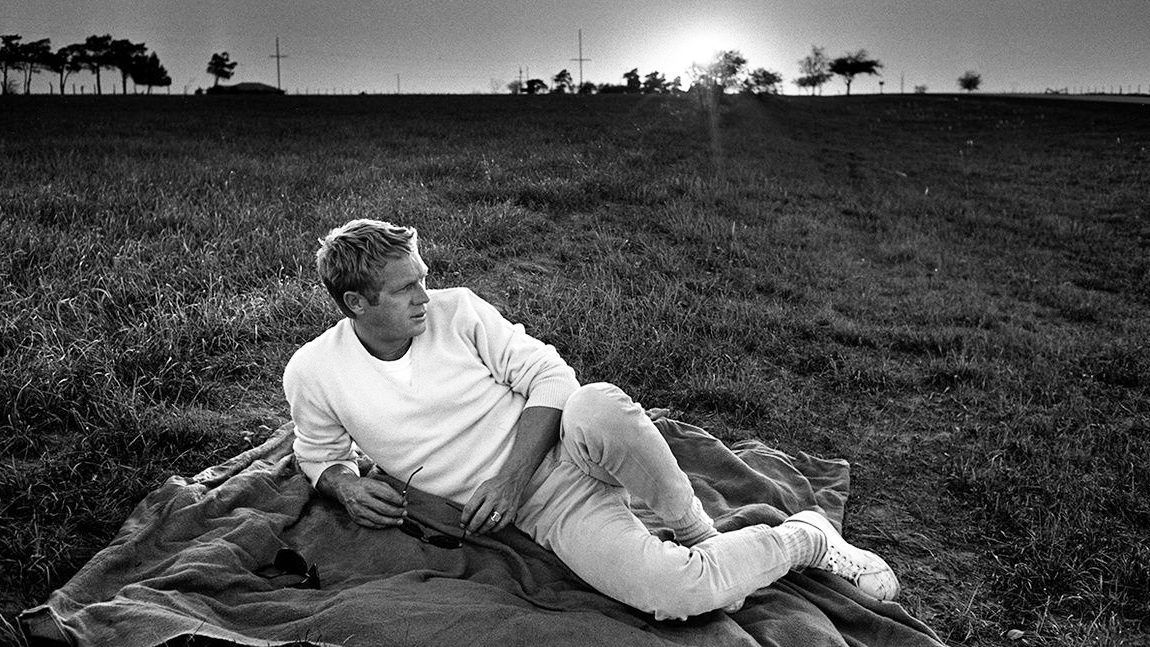

A gentleman’s guide to dolce far niente celebrates the elegance of stillness. True ease requires practice, for idleness done well is the rarest expression of taste.

- Words: Rupert Taylor

There are few phrases that sound better in Italian than they live in English.

“The sweetness of doing nothing” is one of them. It drifts off the tongue like a sigh after lunch and lands somewhere between philosophy and flirtation. Italians call it dolce far niente, and they manage to make idleness look positively noble. The rest of us just look like we forgot what we were doing.

We in Britain, of course, take pride in exhaustion. We treat tiredness as though it were a sport, complete with medals for whoever yawns the loudest in the office lift. We measure our worth in appointments and apologise for lunch breaks as if they were crimes. Yet somewhere south of Florence, an elderly man is sitting under a lemon tree, eating a grape very slowly, and he is doing more for civilisation than your inbox ever will.

The Ancient Art of Absolutely Nothing

To understand dolce far niente, one must first understand that it is not laziness. Laziness is unwashed, unplanned, and usually wearing tracksuit bottoms. Dolce far niente, on the other hand, has linen involved. It is the pleasure of being idle well. It is the deliberate enjoyment of time as it passes, the appreciation of the unremarkable, the exquisite luxury of having nothing to prove.

You may remember Julia Roberts in Eat Pray Love, sitting in a Roman barber’s chair looking slightly too spiritual for a haircut. Her Italian friends chide her for not relaxing properly. She has been in Rome for weeks, they tell her, yet all she has done is visit ruins, learn the language, and catalogue guilt. “Americans,” says one, “you work too hard to enjoy yourselves.”

They pour wine, they smile, and with theatrical understatement, one of them says,

“Dolce far niente.”

She laughs politely, but they are entirely serious. They are teaching her, and us, the most delicious lesson of all.

What the Phrase Really Means

Translated crudely, dolce far niente means “sweet doing nothing.” But the Italians do not mean nothing in the literal sense. They mean something closer to “existing attractively.” It is the art of sitting still with intent. You are not slouching; you are composing yourself. You are not wasting time; you are marinating in it.

It is a kind of cultivated stillness that the English find deeply suspicious. We prefer to be seen striving, even when we are secretly scrolling. We admire the busy because they appear essential. But the Italians admire the idle because they appear free.

Dolce far niente is the opposite of hustle. It is the polite rejection of pressure. It is the understanding that pleasure requires presence. If mindfulness is therapy for the stressed, dolce far niente is leisure for the already cured.

How to Do Nothing Beautifully

The beginner’s mistake is to think one can simply sit down and begin. You cannot. The art of doing nothing is like tailoring or tennis; it must be practised until effortless.

Step one: location. Choose a setting that flatters the act. Rome, ideally. Failing that, somewhere with chairs, shade, and an acceptable wine list. A terrace will do. The lighting should suggest that time has no particular intention of moving on.

Step two: accoutrement. You may bring a newspaper, but under no circumstances should you read it. You may order coffee, but you must sip it slowly enough to concern the waiter. You may wear sunglasses, but only if you remove them periodically to appreciate the architecture.

Step three: attitude. Look faintly amused by existence. Pretend to be contemplating a philosophical matter when in truth you are admiring the symmetry of your drink. The secret is serenity mixed with just enough smugness to imply enlightenment.

If you can master these three steps, congratulations, you have joined an elite international order of people who are good at being unproductive in style.

Why We Are So Terrible at It

The British, and our distant cousins across the Atlantic, have a fraught relationship with leisure. We confuse rest with guilt and idleness with failure. Even our weekends require strategy. “Relax,” we tell ourselves sternly, and immediately book a yoga class, a roast, and a quick spin class to unwind from both.

Our phones, meanwhile, ensure that even when we are doing nothing, we are performing something. We are documenting our detachment. We are performing relaxation for an invisible audience. The Italians would never. They would sooner miss a train than take a selfie.

When they say dolce far niente, they mean the sweetness of doing nothing without apology. The modern man must learn that permission is not required. You may rest. You may watch dust in sunlight and call it contemplation. You may sit, look lovely, and achieve nothing measurable. It is, in fact, the highest mark of civilisation.

The Economics of Leisure

Time, that rarest of currencies, is spent too freely by those who do not know its worth. We treat it like pocket change, scattering it into screens, emails, and minor obligations. The Italians invest it differently. They place it in afternoons, espresso cups, and unhurried conversations. They let it mature.

To do nothing well is to announce, quietly, that one’s time belongs to oneself. It is wealth without arrogance. The man who can spend an hour doing nothing with perfect composure has understood value more profoundly than the man who fills every minute.

And there is, of course, luxury in this. To work implies necessity. To rest implies choice. And choice, as any man of taste will tell you, is the purest form of power.

The Sweet Science of Stillness

The beauty of dolce far niente lies not in what happens, but in what doesn’t. The pause becomes a statement. The absence of action becomes a form of elegance.

Consider a fine watch ticking quietly on a bedside table. Its movement is constant, its sound discreet, its purpose unhurried. That is dolce far niente. It does not chase the minute; it simply marks it.

Likewise, a man who knows when to stop, who can recline with conviction and smile faintly at the chaos around him, is far more compelling than the man who insists on conquering every calendar alert. The first man suggests control. The second merely suggests exhaustion.

Practising the Sweetness

You can begin small. Take a walk without earphones. Have breakfast without news. Sit in a park with no book, no task, no deadline. Listen to the absurdity of birds having opinions. Watch a cloud behave badly.

If you manage an hour of this without checking your watch, you have begun. In time, you will progress to longer intervals, entire afternoons, perhaps, dedicated to sitting somewhere attractive and doing absolutely nothing. People may assume you are deep in thought. Let them. Deep thought and no thought look remarkably similar when done with confidence.

There is no official certificate for dolce far niente, but the man who perfects it is instantly recognisable. His voice is calm, his gestures are deliberate, his email replies are refreshingly brief. He looks rested in a world that worships the restless.

A Note on Julia Roberts and Other Seekers

When Julia Roberts, in that now-famous film scene, learns the term from her Roman companions, she looks incredulous, partly because she suspects she might enjoy it. She smiles, sips, and begins to understand that joy can exist without effort. It is the most important scene in the film, and perhaps the most Italian lesson Hollywood has ever accidentally delivered.

The audience laughed because they recognised themselves: running about, over-scheduled, perpetually anxious about doing something worthwhile. The Romans simply looked amused. They already knew. They had invented the art of looking purposeful while doing absolutely nothing centuries earlier.

Why the World Needs It Now

We live in an age that mistakes urgency for importance. Every message, every notification, every invented emergency demands our immediate devotion. But there is rebellion in refusal. To sit still is to reclaim one’s humanity from the machinery of momentum.

Dolce far niente is not laziness, nor indulgence. It is therapy disguised as elegance. It is a reminder that pleasure does not need to be purchased or posted. It can be found in the curve of a spoon, the breeze through curtains, the satisfying clink of a teaspoon against porcelain.

And though it may sound like poetry, it is, in fact, practice. To stop, to breathe, to smile, to do these things consciously is to be alive in full measure.

The Gentleman’s Epilogue

Ultimately, dolce far niente is less a hobby than a declaration of taste. It says: “I have nothing to prove and nowhere better to be.” It is the art of reclining gracefully while the world spins itself into knots.

So tomorrow, find a chair that pleases you. Order something simple. Leave your phone somewhere unimportant. Sit very still, admire something meaningless, and when someone asks what you are doing, look them squarely in the eye and say, “Nothing. But I am doing it beautifully.”