Best Cigar Lighters

In a culture that too often mistakes abundance for discernment, the finest American cigar lighters are those that vanish into the ritual itself. They serve with poise and proportion, igniting more than tobacco, a brief communion between fire and intent.

- Words: Gentleman's Journal

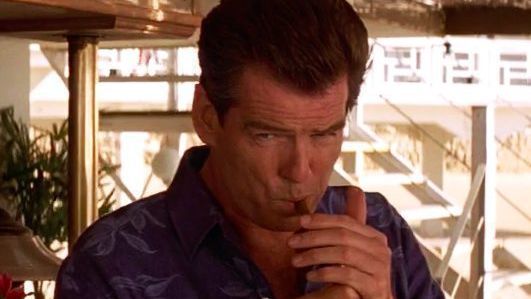

There are few gestures as revealing as the way a man lights a cigar. It is a small ritual: wordless, deliberate, never hurried, and yet it says everything about his relationship with time, taste, and composure. A lighter, properly chosen, does more than ignite tobacco; it sets the tone for the whole encounter. The precision of the flame, the sound of the hinge, the weight of the metal against the fingers; all these small notes combine into an overture of civility.

In America, this ceremony has its own particular timbre. The country’s relationship with cigars has long been a blend of enterprise and indulgence, equal parts craftsmanship and confidence. In the wood-panelled clubs of New York or the verandas of Florida, the cigar has always been an emblem of achievement, but never of hurry. One smokes not to impress, but to pause. And the lighter, often overlooked by those who have not yet learned to slow down, serves as the conductor’s baton in this unspoken orchestra of leisure.

If European tradition gave the world refinement, America has given it vigour. The American lighter is born of that union; precision engineering softened by design, practicality elevated by taste. Whether drawn from Parisian ateliers or forged in Midwestern workshops, the best of them share the same quiet virtues: balance, endurance, and a sense of purpose so complete that it never needs to announce itself.

What follows is a study in those virtues, six lighters that represent the finest synthesis of design and performance, each chosen not for extravagance but for their ability to civilise a fleeting act of fire.

S.T. Dupont Le Grand

There are lighters, and then there are S.T. Duponts. Founded in 1872 by Simon Tissot-Dupont as a maker of travel trunks, the Parisian house turned to the alchemy of fire in 1941, producing its first metal lighter for officers who required both elegance and reliability. Eight decades later, the Le Grand remains its most complete statement of intent; a confluence of craft, technology, and almost unreasonable precision.

Every detail is engineered as if for a chronometer. The lid opens with that crystalline “cling” collectors can identify from across a room, a sound born not of chance but of harmonics; the tone produced by the tension between lid and body. The roller resists the thumb just enough to feel purposeful. Half a motion yields the soft flame of tradition, while a full press awakens twin torches, blue and sharp, for the modern smoker. Nothing rattles, nothing wobbles. The hinge moves with the authority of a camera shutter, and the body, clad in palladium or natural lacquer, has the measured heft of a fountain pen.

To light a cigar with a Dupont is to participate in the French art of understatement. The act is precise but never hurried, indulgent without indulgence. It is the difference between a good suit and a bespoke one; nobody else will notice, yet one cannot go back.

Dunhill Rollagas

If Dupont is the sonata of Paris, Dunhill is the silence of London between the notes. Alfred Dunhill’s company began in 1893, equipping early motorists with the discreet accoutrements of progress: goggles, gloves, pipes, and eventually lighters. The Rollagas arrived in 1956 and almost immediately defined a category, the gas lighter as an object of English discretion.

It remains astonishingly modern. A slender oblong, its edges softened by guilloché engraving, it sits in the palm like something discovered in a gentleman’s drawer and never improved upon. The roller turns with that particular mechanical calm familiar to watch collectors; firm, silent, certain. The flame emerges without fuss, a neat, wind-resistant column the colour of champagne light. There is no drama; the performance is entirely in the restraint.

Dunhill’s design language has always been about discipline, lines instead of curves, proportion instead of shine. The Rollagas exemplifies this aesthetic so completely that to change it would be to spoil it. It belongs beside a leather-bound notebook or an old lighter case bearing the initials of a grandfather one never met. British elegance is not about display; it is about continuity disguised as simplicity.

Colibri Julius

Colibri’s story begins in 1928, when Julius Löwenthal sought to simplify the small rituals of modern life. His first automatic lighter captured the optimism of the Jazz Age; the Julius model, released nearly a century later, honours that original without indulging in nostalgia.

The body recalls the geometry of the period, with vertical fluting, a satin finish, and the suggestion of speed frozen in metal. Yet beneath its Deco surface lies contemporary engineering: a dependable flint wheel, a refill system refined through decades, and a flame that remains steady even in open air. The Julius invites a slower rhythm. The ignition, smooth but deliberate, demands attention; the soft orange flame is for the contemplative smoker, not the hurried one.

In the hand, it feels human, not manufactured. The edges are warm, the weight modest. It suits evenings when conversation matters more than spectacle. One can imagine it resting on a piano during a dinner party in 1932, then in a modern apartment a century later, unchanged in purpose. Colibri’s achievement lies in making an old shape breathe again, proof that design, when honest, does not age so much as deepen.

Xikar HP3 Triple Jet

American in spirit and temperament, Xikar was founded in 1996 by Kurt Van Keppel and Scott Almsberger, who wanted a cigar cutter that worked properly. Lighters soon followed, each one a small lesson in the American knack for over-engineering a simple idea until it becomes excellent. The HP3 Triple Jet is a case in point, a device born from utility yet executed with grace.

Three jets sit in a triangular formation, angled to converge at precisely the right distance for an even toast. The result is a flame both ferocious and controlled, as if tuned by an aerospace engineer with a poetic streak. The body is cast from anodised alloy, its panels subtly curved, and the trigger placed exactly where instinct expects it. The ignition sounds faintly like the click of a rifle: sharp, confident, final.

Yet there is no brashness in the design. The HP3 carries its strength quietly, like an athlete in formalwear. It performs flawlessly in the wind, at altitude, and in the chill of early-morning tee times. It belongs to the pragmatic American gentleman who values reliability as a virtue in itself. Where Europe refines through heritage, Xikar perfects through persistence, and the result is no less elegant.

Zippo Blu and Slim

If America has an icon of fire, it is Zippo. Founded in 1932 by George G. Blaisdell in Bradford, Pennsylvania, the company built its reputation on a promise of permanence: “It works, or we fix it.” Soldiers carried Zippos through war; artists flicked them open in films; generations kept them as small, loyal companions. To hear that distinctive metallic click is to hear America light something and move forward.

The modern Blu and Slim editions refine that legacy. The Blu replaces the traditional wick with a butane torch, marrying old ritual with modern efficiency. The Slim retains the flint and wick but pares the form to elegance, a kind of Zippo in evening dress. Each lid still opens with the same two-note cadence of hinge and click that collectors recognise instantly.

A Zippo is democratic, indestructible, and oddly intimate. Its patina tells stories of pockets and years, and its sound announces not wealth but constancy. To light a cigar with one is to acknowledge the romance of the American hand-made: the workshop in Bradford still humming, craftsmen still assembling by hand, the design still defiantly unchanged. In a world of disposable flame, the Zippo remains a small act of permanence.

Davidoff Prestige Lighter

The Davidoff name, born in Geneva in 1911, has long stood for the elegant side of precision. Zino Davidoff’s philosophy of simple luxury executed flawlessly permeates every object that bears his signature, and nowhere more than in the Prestige lighter.

It is a study in proportion. The chassis, slim and unadorned, feels almost architectural; the brushed finish catches light without sparkle. The ignition, a single motion, releases a narrow jet of flame as steady as a metronome. There is no hiss or clatter, only the calm release of controlled combustion.

Everything about it whispers of engineering discipline. The tolerances are microscopic, the mechanics invisible. It neither seeks attention nor suffers it. A Davidoff lighter suits those who prefer their pleasures private, who find satisfaction in the quiet alignment of parts that fit perfectly.

To own one is to subscribe to a philosophy of refinement without narrative. The Prestige does not commemorate anything, does not flaunt its maker’s mark; it simply is, which may be the highest compliment one can pay an object of use.

Eagle Torch USA

In the pantheon of polished metal and lacquer, the Eagle Torch appears almost utilitarian, but that is precisely its virtue. Manufactured in America since the 1990s, the lighter began as a tool for mechanics and outdoor enthusiasts before being adopted by cigar smokers who cared more for reliability than lineage.

Its appeal is immediate. The casing, often transparent polycarbonate or brushed aluminium, reveals the mechanism within: the gas reservoir, the piezo ignition, and the simple lever that controls the flame. Press it once, and a blue column appears, unwavering even in a gust. It may lack the Dupont’s musicality or the Dunhill’s engraving, but it delivers something rarer: trust.

Owners tend to keep them for years, repairing rather than replacing. The surface scratches, the metal dulls, yet the performance never falters. There is a plain dignity to that. The Eagle represents a particular American honesty, the belief that excellence can exist without ceremony. In its steadfast refusal to be precious, it becomes quietly precious indeed.

The Final Draw

Seven lighters, seven philosophies of fire. From Dupont’s Parisian poise to Dunhill’s London reserve, from Colibri’s Deco romance to Xikar’s engineering, from Zippo’s Americana to Davidoff’s Swiss purity and Eagle’s unassuming integrity, each transforms the fleeting act of ignition into something lasting.

What unites them is proportion: every hinge, roller, and jet balanced between necessity and grace. The pleasure lies not in the blaze itself but in the moment before, the small anticipation as metal meets thumb, the poised second of silence, the flare that follows. These are not objects to be flaunted but to be trusted, companions in a ritual that remains one of life’s gentler defiances against speed.

To light a cigar well is to acknowledge time, to admit that some gestures still deserve precision. The right lighter offers more than flame; it offers the rare comfort of knowing that something, at least, has been made perfectly.

Further reading

The Country Gear Guide