A Review Of The Apple Vision Pro (2026) | A Triumph of Brilliance

Apple Vision Pro feels like the future wearing silk gloves. It dazzles, it disorients, and it proves that brilliance can sometimes arrive with the faint air of vanity.

- Words: Rupert Taylor

There comes a moment in every gentleman’s life when he realises he owns more screens than books. I encountered this revelation somewhere between my iPhone, my MacBook, my television, my smartwatch, my car display, and now (inevitably) my face. For Apple has produced a device that allows one finally to wear one’s own delusions of productivity as headgear. It’s called the Apple Vision Pro, and it is, by any civilised measure, both magnificent and faintly absurd.

I’ve spent a fortnight with the thing: writing, watching, gesturing in mid-air like a man conducting invisible orchestras. What follows is not merely a review, but an account of what happens when one allows Cupertino to annex one’s peripheral vision.

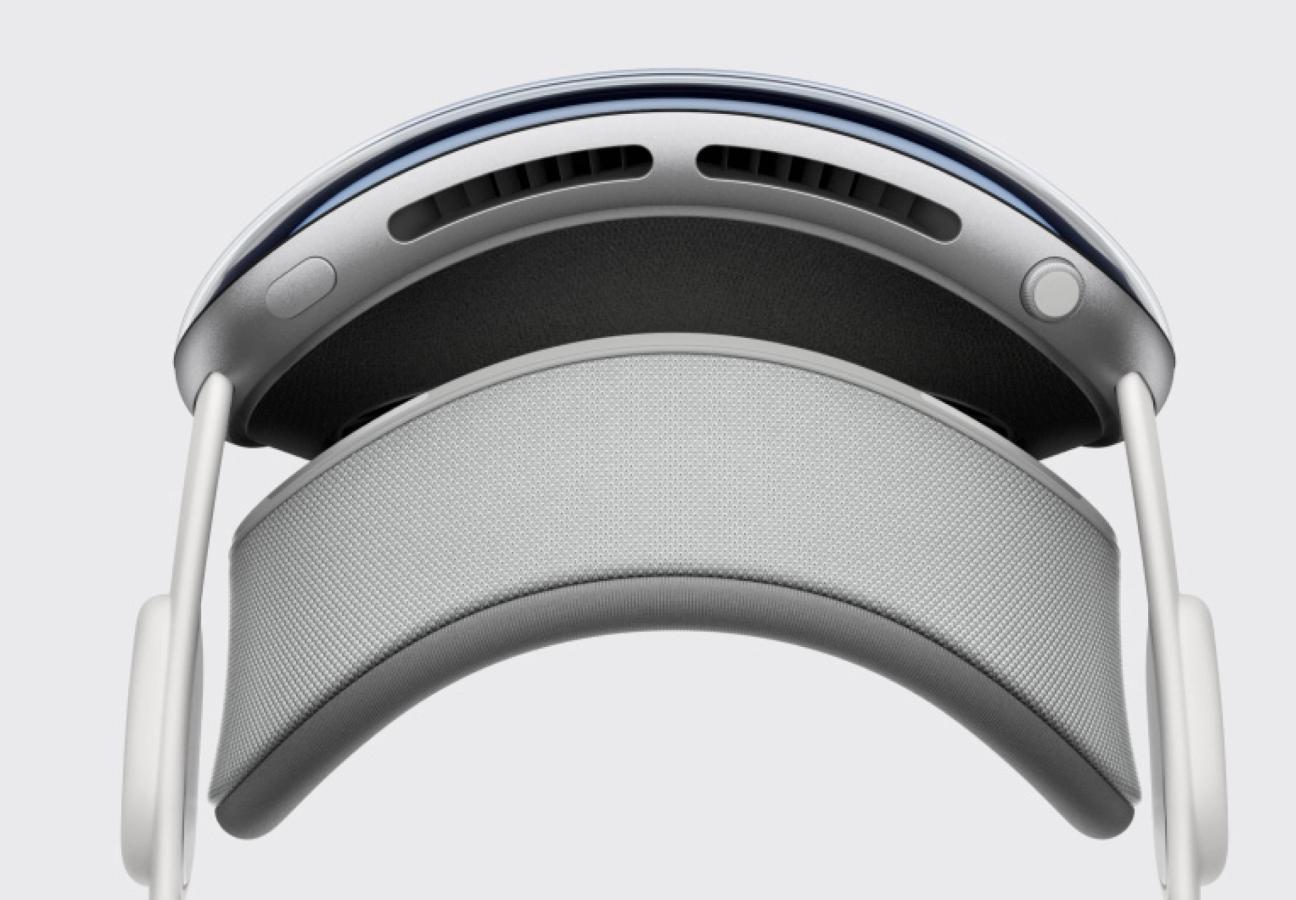

Apple Vision Pro Design and the Ski Goggle Status Symbol

The Apple Vision Pro is undeniably beautiful, in the way that a Bond villain’s surveillance equipment is beautiful. Aluminium curves meet laminated glass with surgical precision. The device gleams; it purrs with competence. One slips it on and immediately feels either like the future of work or the world’s most expensive welder.

It is, however, substantial. The headset weighs roughly the same as an existential crisis. Apple has worked miracles with the balance, but no amount of mesh padding can disguise the fact that you are wearing a small iMac on your skull. A white cable slinks down to a battery pack that looks like something one might use to jump-start a Tesla. Apple calls this an “external power solution.” The rest of us call it a wire.

Still, it’s a beautiful wire. The aluminium casing would not look out of place beside a Patek Philippe. And in fairness, one soon forgets the discomfort, rather as one forgets the cost of a Mayfair flat once the view distracts.

Display Quality and Micro-OLED Experience

The Vision Pro’s twin micro-OLED screens deliver more pixels than one should reasonably be allowed to perceive before lunch. Each eye receives its own 4K image, a private cinema projected directly into the cortex. Text appears razor-sharp; films shimmer with unnatural clarity; one can see the pores on actors’ pores. The result is intoxicating, like discovering sight for the second time, but sponsored by AppleCare.

When you launch a film, the world politely dissolves. Your drab sitting room becomes a 100-foot screen hovering over the Dolomites. You may, if you wish, enlarge it until it engulfs the horizon and your sense of proportion. I watched Lawrence of Arabia like this and felt, for the first time, that Lawrence himself might stride through the kitchen at any moment demanding espresso.

Apple’s spatial audio completes the illusion. Turn your head, and the soundscape rotates with you, an orchestra of obedience. It’s astonishing and slightly unnerving, as though the universe has agreed to follow your gaze out of politeness.

Controls and the Art of Invisible Orchestras

The first revelation of the Apple Vision Pro is how little you need to touch it. The second is how ridiculous you look while not touching it. Control is via eye-tracking and finger-pinching, a system so intuitive that within minutes you’re swiping windows around your living room like a caffeinated civil servant.

To select something, one simply looks at it and performs a discreet pinch. Apple insists it’s “natural.” In practice, it’s rather like attempting to catch a fly that owes you money. After an hour, I resembled a man signalling ships from a desert island.

Voice control, mercifully, works well, though one quickly learns not to dictate emails aloud if there are others present. There is no elegant way to say

“Dear Nigel, please find attached the quarterly revenue forecast”

while wearing a visor the size of a salad bowl.

Performance and the Art of Excess

Inside lurks Apple’s M5 chip, which performs feats of computation so vast that one suspects it occasionally solves crimes on the side. Applications open instantly, 3D environments render without a stutter, and the Mac Virtual Display feature allows one to summon an enormous floating version of one’s laptop screen. It is quite literally a desktop in the clouds.

Working in the Vision Pro is initially exhilarating. Your email hovers to the left, your calendar to the right, and a news feed drifts somewhere above your ego. Within minutes, you’ve recreated the chaos of your real desktop, but with depth perception. Apple calls this “spatial computing”; I call it “three-dimensional procrastination.”

Battery life remains politely brief, about two hours if you’re watching films, slightly less if you’re “revolutionising your workflow.” Plugged in, the device runs indefinitely, though so, alas, do the neck muscles required to support it.

Software and the Exquisitely Furnished Waiting Room

visionOS, Apple’s new operating system, is a triumph of design and diplomacy. It looks and feels exactly like iOS, only suspended in space and slightly smug about it. Icons float in soft focus, menus glide into view with the confidence of a maître d’.

There are apps for work, for media, for meditation, and (inevitably) for mindfulness, which is ironic given the device’s ability to annihilate awareness of one’s surroundings. You can take “spatial photos” and “spatial videos,” which are essentially three-dimensional memories. They are breathtaking until you realise you’ve trapped your loved ones inside a headset like benevolent Pokémon.

Yet the App Store remains sparsely populated. Developers, ever cautious, appear to be waiting for the rest of us to justify the effort. Apple’s own apps, of course, sparkle, but for now the Vision Pro feels less like a bustling metropolis and more like an exquisitely furnished waiting room for the future.

Everyday Use from Novelty to Necessity

The Vision Pro excels at two things: impressing guests and reminding you that you own it. In both cases, it performs flawlessly.

For productivity, the experience is promising but faintly comedic. I composed part of this review within the headset, gazing at a floating document while occasionally colliding with furniture. Dictation is accurate; typing on a virtual keyboard, less so. There is a tactile absence; one longs for the reassuring click of keys, the analogue punctuation of thought.

Watching films is sublime; reading documents is tolerable; navigating spreadsheets is a punishment best reserved for enemies. As for gaming, there are diversions, but the Vision Pro is far too well-bred to encourage actual fun. It prefers experiences: meditative walks through Tuscany, simulated art galleries, documentaries narrated by calm Americans who sound as though they, too, cost $3,499.

Which brings us neatly to price.

Price and the Cost of Tomorrow

Three and a half thousand dollars, or roughly the price of a week in Provence, buys you entry into Apple’s new dimension. At that figure, one might expect the device to iron shirts, manage portfolios, or at least make small talk. Instead, it grants the privilege of telling your friends, “It’s not VR, it’s spatial computing,” which is rather like insisting your yacht is a “marine workspace.”

To Apple’s credit, every component justifies its cost in craftsmanship if not necessity. The packaging alone could be displayed at the Design Museum. But one suspects the Vision Pro’s true value lies in its symbolism: owning one announces that you are both visionary and available for beta testing.

As with any luxury, exclusivity is part of the allure. Most people will try one in an Apple Store, gasp, and retreat to reality. A select few will buy it, declaring it “the future of work” while secretly using it to watch football highlights the size of a cathedral.

Shortcomings and Real-World Drawbacks

If this were a Yes Minister memo, the drawbacks section would read: The device demonstrates significant potential for transformative engagement, subject to minor inconveniences such as weight, warmth, social ridicule, and existential isolation.

Translated from civil-service English: it’s heavy, it gets warm, you look ridiculous, and after a while you miss faces. The Vision Pro’s greatest flaw is the solitude it creates. Apple’s designers have attempted to solve this by projecting your eyes onto the outer display, a feature called EyeSight, which allows others to see a ghostly approximation of your gaze. The result, sadly, is less “approachable human” and more “haunted aquarium.”

Comfort, too, remains a compromise. Two hours is fine; three hours and you start to envy decapitation. And while the interface is sublime, it occasionally misreads intentions. On one occasion, I meant to close a window and instead dialled my accountant, which felt prophetic.

What It All Means Beyond the Glass

Apple claims the Vision Pro will redefine computing. It may also redefine loneliness. The headset encapsulates our age: magnificent technology in search of a problem grand enough to justify itself. It invites us to retreat from the physical world into an immaculate simulation, curated to our exact preferences, and to call it progress.

There is, admittedly, a certain grandeur in Apple’s ambition. The Vision Pro is less a product than a thesis: that reality is negotiable, provided it renders in 4K. It extends the company’s aesthetic of smooth surfaces and smoother experiences until friction itself feels like an error message.

But one can’t escape the suspicion that this perfection is sterile. The Vision Pro’s environments are too flawless, its gestures too graceful, its lighting too kind. The chaos of real life, the smudge on the glasses, the breeze through an open window, has been debugged out of existence. You emerge from a session blinking at the real world as if it’s under-rendered.

Verdict and the Gentleman at the Glass Frontier

So, is it worth it? The short answer is yes, provided you can afford to buy one for curiosity rather than salvation. The Vision Pro is the most impressive piece of consumer technology since the smartphone, and possibly the least necessary. It is both the future of computing and an exquisite cul-de-sac.

For the gentleman of means, it represents the ultimate conversation piece, an artefact of aspiration. To slip it on is to declare, “I have seen tomorrow, and it is high-definition.” To slip it off is to remember that tomorrow, like today, still requires breakfast.

I find myself oddly fond of it. I admire its engineering, its bravura, its refusal to apologise for being marvellous. Yet I’m relieved each time I remove it, as one is relieved to take off formal shoes after a gala dinner. Greatness, it turns out, is heavy.

In the end, the Vision Pro reminds me of a line Sir Humphrey once used about a doomed government initiative: “It will, Minister, create a great many advantages for a very small number of people, and a great many disadvantages for a slightly larger number of people, but on the whole it will be regarded as a success.”

Quite so. The Vision Pro is a marvellous success, just not for everyone. It is luxury made literal, the apotheosis of Apple’s genius for desire. It asks not whether you need it, but whether you deserve it. And in 2026, that may be the most Apple question of all.