Why Rolex Is so Expensive

Industrial consistency at huge scale costs money, and so does control over distribution. Add waiting lists, resale gravity, and pricing power, and it becomes clearer why Rolex is so expensive.

- Words: Rupert Taylor

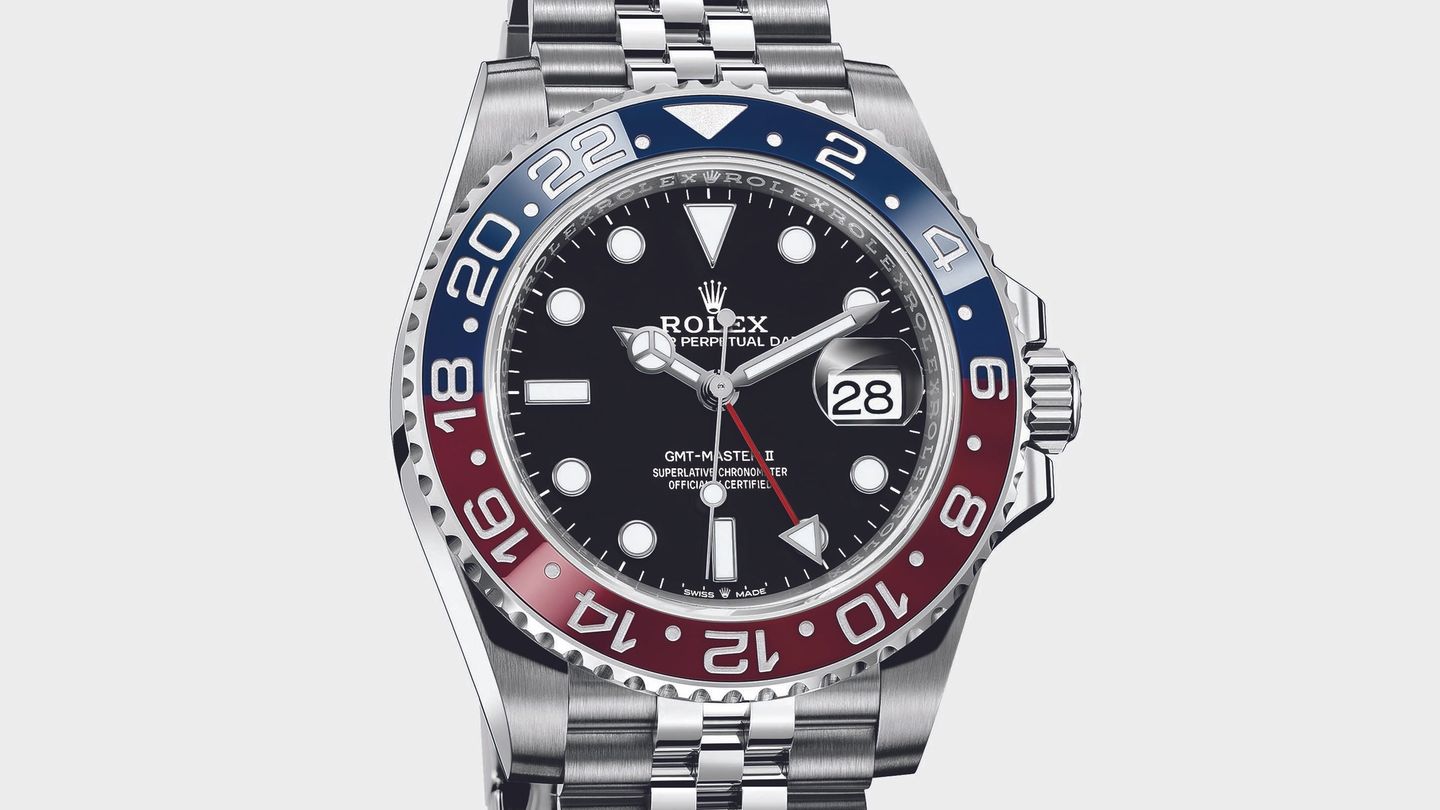

There are objects that function perfectly well as what they are, yet somehow become something else entirely. A wax jacket is still a jacket. A martini is still a drink. A well-cut suit remains, at heart, stitched cloth. And then there is a Rolex, which is ostensibly a mechanical watch, but behaves more like a small, portable declaration of competence. Not the loud sort, thank you. The quieter variety, delivered with the faintly reassuring air of someone who has read the briefing and brought the correct folder.

You can, of course, ask why a Rolex costs what it does. People do. They ask in the same tone they use for private schools and Italian furniture, as if the answer will reveal an underlying scam, or at least a rather cheeky administrative surcharge. Yet the truth is more interesting, and slightly more British. Rolex is expensive because it has mastered the peculiar art of making the practical feel inevitable, the luxurious feel earned, and the merely desirable feel like policy.

If that sounds like a plotline from Whitehall, it is because it practically is.

Rolex Does Not Sell Time, It Sells Assurance

Time is available everywhere. Your phone displays it with the generosity of a public service. Your laptop offers it in the corner, like a minor official waiting for instructions. Even the microwave insists on it, though it cannot be trusted. Rolex, meanwhile, sells you a particular feeling about time. A sense that the world might be in a state of constant negotiation, but your seconds are being counted by something that does not negotiate.

This is an emotional product dressed as an instrument. It says you value punctuality, continuity, and things that work today in exactly the way they worked yesterday. It also says you have chosen a symbol that other people recognise instantly, without requiring you to explain yourself. Which is the whole point of status, really. If you must clarify it, it is not doing its job.

There is also the deeper appeal, the one men rarely confess to unless several drinks in. A Rolex offers a kind of reassurance about one’s own story. It suggests you have arrived, or are at least en route with purpose. It implies you do not merely have plans, you have follow-through.

Engineering That Prefers Reality to Romance

Luxury loves the word handmade, because it conjures candlelit workshops and artisans with heroic eyebrows. Rolex prefers something less poetic and far more expensive. It prefers repeatable excellence at scale.

Rolex makes an enormous number of watches by luxury standards, yet it does so with a level of consistency that most brands can only dream of. The trick is not a single miraculous craftsman. It is an entire industrial culture built around precision, testing, and process. That kind of competence costs money in the same way good governance costs money. You can cut corners, but then you are no longer in charge of outcomes.

A Rolex movement is designed to survive a life, not a photoshoot. It is built to keep time through knocks, temperature shifts, travel, and the various indignities of daily wear, including the occasional brush with a door frame that you will absolutely deny happened. The company’s obsession with durability is not marketing. It is an engineering philosophy. There are watches that are more delicate, more intricate, even more artistically daring. A Rolex is the one you would trust when you cannot afford surprises.

That reliability is an underrated luxury. People romanticise fragility because it seems rare and special. Reliability is rarer because it requires discipline, and discipline is exhausting.

Materials, Provenance, and a Certain Swiss Stubbornness

Part of the Rolex premium lives in the materials, though not in the crude way people imagine, as if it is simply a matter of adding a bit of gold and calling it a day. Rolex has a reputation for being fussy about what it uses, and fussiness is rarely cheap.

Take steel. Steel sounds like the democratic option, until you notice how different steels behave over time. Rolex selects alloys that resist corrosion and polish beautifully, which means the watch retains its presence year after year. It does not turn into something tired and apologetic. It stays crisp. It stays assured. It keeps its composure, which is more than can be said for most of us by late Thursday afternoon.

Then there is gold, and here Rolex becomes almost comically self-sufficient. The brand has long used its own foundry for its precious metals, which is the horological equivalent of insisting on growing your own tomatoes because you do not trust the shop. This is not merely indulgence. It is control. Control means consistency, and consistency is what turns a product into a signature.

Even the less glamorous components matter. The sapphire crystals, the gaskets, the bracelets, the clasps that snap shut with that satisfying finality, all of it is built to a standard that prioritises longevity. Rolex does not want you to feel you are wearing something delicate. It wants you to feel you are wearing something inevitable.

Testing, Certification, and the Cult of Not Being Embarrassed

A Rolex is expensive partly because it is tested like a civil servant being vetted for access to awkward information. Movements are regulated, watches are checked, and performance is monitored. The point is not simply accuracy. It is confidence.

Rolex has its own standards and testing regimes, and it also intersects with broader Swiss certification culture. The details can become technical, and there is no faster way to clear a dinner party than to explain tolerances in microns. What matters for the buyer is simpler. You are paying for an object that is extremely unlikely to embarrass you.

That sounds trivial until you consider what luxury really is. Luxury is the removal of friction. It is the disappearance of problems you did not know you were meant to have. A Rolex is engineered to reduce the number of moments in which you think, Is this still working, Is this still accurate, Is this still respectable.

You might not notice that peace of mind daily, but you will notice its absence the moment something cheaper lets you down, usually when you least have the patience for it. Reliability is a kind of quiet power, and Rolex has made a religion of it.

Scarcity, Waiting, and the Administrative Theatre of Desire

Now we come to the part everyone discusses in a lowered voice, as if the walls might be listening. Scarcity.

Rolex produces a great many watches, yet demand is greater still. Some models, particularly the ones that have become cultural shorthand, are difficult to obtain at retail. This is not an accident. It is also not quite a conspiracy, though it does have the pleasing feel of a well-managed system.

Scarcity creates narrative. It turns a purchase into an event. It introduces the thrill of pursuit, the whispered advice, the referrals, the slightly awkward conversations with authorised dealers that resemble a job interview, except you are interviewing for the right to spend money. This sounds absurd, and it is. Yet it works because it flatters the buyer. It suggests discernment, patience, and access.

In Yes Minister terms, it is the perfect arrangement. The public believes it is chasing the object, while the institution quietly decides the terms of the chase. It keeps the brand desirable, it keeps the market animated, and it keeps everyone talking. If the watches were always available, they would still be excellent, but they would feel less momentous.

Waiting, in luxury, can become a feature rather than a bug. It implies demand. It implies selectiveness. It implies you are not buying something. You are being allocated something. Nothing says status quite like allocation.

Branding So Strong It Barely Needs to Raise Its Voice

Many brands advertise. Rolex announces, but rarely pleads.

Its marketing has long been associated with achievement, endurance, exploration, and sport. These associations are not random. They build a story in which the watch is not merely worn, it is earned. It becomes the companion of the capable. That narrative lands particularly well in the modern world, where capability is often performed rather than proven. A Rolex offers a shortcut. It suggests the proof has already happened.

The clever part is that Rolex rarely has to reinvent itself. Its design language is recognisable, consistent, and conservative in the best sense. It does not chase trends. It allows trends to pass by while it continues to look like itself. That steadiness becomes part of the value proposition. You are not buying into a season. You are buying into continuity.

This is also why a Rolex is legible across social contexts. Watch enthusiasts respect the engineering. Non enthusiasts recognise the silhouette. People who barely know what a movement is still understand what a Rolex implies. It is a universal symbol, which is rare, because most symbols fracture by tribe. Rolex has managed to stay broadly understood, and broad understanding carries a premium.

The Secondary Market, or How Value Learns to Multiply

There is another factor that inflates the Rolex phenomenon, and it is both practical and faintly intoxicating. The secondary market.

When certain Rolex models trade above retail, a psychological shift occurs. The watch stops being merely a purchase and starts being treated as a form of stored value. People begin speaking about it with the language of assets, even if they would never admit it outright. That dynamic fuels demand further, because many buyers like the idea that their taste is also, conveniently, prudent.

This is where the system becomes self-reinforcing. High demand leads to scarcity. Scarcity leads to higher secondary prices. Higher secondary prices lead to more demand, because people fear missing out, and because they assume the market is validating their desire. At that point, the object becomes more than the object. It becomes a token in a social and financial game.

It is worth noting that markets can cool, and tastes can shift. Yet Rolex has shown a remarkable ability to remain central even when the conversation changes. Partly because the brand is not built on novelty. It is built on trust, and trust is a stubborn currency.

Craftsmanship You Can Feel, Not Just Admire

There is a moment, usually when you first fasten the bracelet properly, when the Rolex price begins to make a certain sense. Not because you have rationalised it, but because you can feel where the money went.

The bracelet articulates with a smoothness that feels engineered rather than accidental. The clasp closes with a decisive click that has the calm authority of a door being locked by someone who has done this for years. The case finishing catches light in a way that looks deliberate, not flashy. The watch sits on the wrist with a kind of physical confidence. It feels like equipment, not jewellery, even when it is very clearly jewellery.

This tactile quality is difficult to quantify, which is why it is so often dismissed by people who have not handled the real thing. Yet luxury lives in small interactions. The way something moves. The way it resists wear. The way it remains pleasing after the novelty fades. Rolex is engineered to still be satisfying in the boring middle of ownership, long after the initial excitement has passed.

That long horizon is part of the cost. If you build something to endure, you charge for endurance.

So, Why Is Rolex So Expensive, Really

Because it is not priced like a simple consumer good. It is priced like a combination of engineering, materials, consistency, scarcity, and cultural power, all wrapped into an object that fits under a cuff.

You are paying for precision manufacturing that favours reliability over romance. You are paying for materials chosen with long-term behaviour in mind. You are paying for testing that reduces the chance of disappointment. You are paying for a brand that has made itself both iconic and oddly discreet, a difficult balance that takes decades to achieve.

You are also paying for the theatre. The polite scarcity. The waiting lists. The sense of a system humming away behind the scenes, ensuring the watch remains desirable, and therefore remains expensive. It is, in a way, the most beautifully run bureaucracy in luxury, with excellent polishing.

And then, finally, you are paying for the simplest thing of all. The way it makes you feel when you glance at your wrist in a moment of mild chaos and see an orderly sweep of seconds, doing its job without drama, as if to say that some parts of life can still be relied upon.

In an age of constant updates, that kind of certainty does not come cheaply. It never has.