One of the mobsters who inspired The Godfather‘s Don Corleone was Frank Costello, a hatchet-faced crime boss whose drink you’d hope never to spill. Costello hailed from Calabria in Italy and came to New York as a child in the late 19th century, shortly before embarking on a life of crime – he smuggled booze during Prohibition, was jailed for assault and robbery, survived a number of whackings by rivals, and died in 1973 aged 82, a respectable innings for a man in his line of work. His career, if you could call it that, would have been strongly influenced by omertà — the code of silence demanded by Italian mafiosi when it came to discussing their profession, especially in the face of the law.

Costello, it is safe to assume, would be turning in his grave to know that today’s mafia has embraced social media, with many of its members and hangers-on posting about their lives with all the abandon of a make-up YouTuber or a Brexity grandfather. Researchers of organised crime in Italy have recently stumbled onto the Facebook pages and Instagram accounts of proper villains who have traded in hits for hashtags and caporegimes for captions.

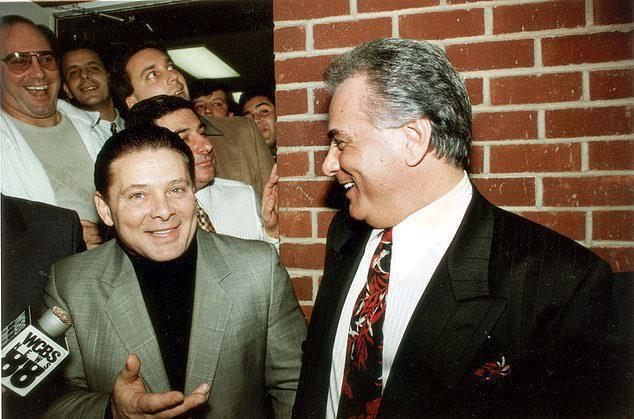

Sammy “the Bull” Gravano has been involved in more than 19 murders — and now has his own podcast

Take the page of Vincenzo Torcasio, alias “Japan”, a top figure in the ’Ndrangheta, the infamous Calabrian crime syndicate, before he was arrested and sentenced to no fewer than 30 years for mafia association and murder. The impression one is given by the severity of Torcasio’s sentence is belied by his Facebook presence. His online persona was a cross between a “Live Laugh Love” aunt and a bloodthirsty killer.

"Villains have traded in hits for hashtags and caporegimes for captions..."

A scroll through his posts, which is highly recommended, reveals his habit of uploading sensitive selfies with tears in his eyes, chin in hand, lost in thought. Typical captions read “What God knows about me is infinitely more important than what others think of me,” and “I will always be there for those who have been there, but for those who have pretended to be there I will be invisible.”

A still from a video by ‘Glock 21’ — AKA Domenico Bellocco — a trap rapper and Calabrian mob member

Amid the dreadful filters and colourful quotes by Oscar Wilde and Albert Einstein, Torcasio posted pictures of Hollywood toughguys with warnings against gossiping behind his back: we see Vin Diesel, Matt Damon, and frequently Wentworth Miller, the erstwhile star of Prison Break (wishful thinking, perhaps). A hint about what he does for a living is visible in a selfie of him pouting like a diva in his car, denouncing the Italian legal system for a strict law that he says unfairly targets honest, hard-working members of the mafia.

“People call you crazy when you do something they would never dare to do,” he says in the caption of another picture – it’s a drawing of Heath Ledger playing The Joker. In another he rails against people who “get everyone arrested with chatter” after being overheard on police microphones talking business. This is not the work of a masterful consigliere. Torcasio might be a few scoops of ricotta short of a cannoli, but running a Facebook page hinting at your criminal enterprise isn’t too far off approaching the Carabinieri and asking if you can put the handcuffs on yourself. And yet he is not the only one at it.

Sammy “The Bull” Gravano

So what is this new generation of mobfluencers in it for? Professor Federio Varese, an organised crime expert at the University of Oxford, believes this is the latest iteration of mafia brand awareness.

“The mafia has always been in the business of brand building, and here the medium has changed, but the aims have not,” he told the Financial Times. “Powerful criminal brands reduce the need to use violence, as if you borrow money from me and know I am in the mafia, you already know I am serious. This reputation helps me avoid violence, which attracts attention, so building it is a very rational investment.”

"The mafia has always been in the business of brand building..."

Dr Anna Sergi, a criminologist at the University of Essex, said mafia use of social media can be used to promote their cultural values — in the same way Unilever might promote its corporate social responsibility on YouTube.

“The mafia identity is not always the same as the activities of the organisation,” she said. “Those who belong to the clans often see it as a lifestyle and way of being, with lots of good in it. For these people it is natural from a criminological perspective to defend your identity and values at a time when they are attacked by the state.”

Domenico Bellocco — mafia member and rising rap star

Both interesting perspectives, but one wonders to what extent it can be applied to the emerging mafia trap music scene. There was a giant hoo-ha last year when Domenico Bellocco, who according to the Italian press is related to the vicious Bellocco crime family of Calabria, arrived on the music scene with Numeri Uno.

Released under his stage name, Glock 21, it is set in Rosarno, described by the local papers as a “grey nightmare” of a town and the video features fast cars, heavy weapons and large jewels. “We don’t give a fuck… We’re number one,” sings Bellocco.

It features various friends and relatives of ‘Ndrangheta big hitters, including one girl whose older brother was on the run when the song came out. Bellocco denied that he is involved in crime, directly or indirectly, and that he was just making art. In a nod to these accusations of flying too close to the mafia, Bellocco’s follow-up track was called Chiamami Boss, Call Me Boss, and in it our man raps on the hood of a Lamborghini about getting nudes on his phone while a blonde woman twerks in front of him. Artful stuff.

"Gravano has more than 10 million views on YouTube..."

The mafia are known for their business acumen, and this might explain another reason for their forays into social media. Consider Sammy “The Bull” Gravano, a ruthless hitman in New York’s Gambino crime family, who posts regularly on Instagram and TikTok. Gravano admitted to being involved in 19 murders — that’s more than the Yorkshire Ripper — and now has a podcast. He’s got more than 10 million views on YouTube for videos in which he regales fans with stories about dragging victims into cars, taking hostages, murdering friends, and disposing of bodies – crimes for which he spent around 20 years in prison. Spotting a gap in the market for mob content online, Gravano is cashing in on his internet celebrity with ad money on viral videos and lots of merchandise – $12 for a mug, $20 for an iPhone case, $500 for a virtual meet-up. It’s not personal. It’s strictly business.

Want more outrage? Here’s Silvio Berlusconi’s larger-than-life career…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal member. Find out more here.

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.