Step inside Steinway’s opulent Hamburg piano factory

Gentleman's Journal head to Hamburg to find out what goes into the world's most intricate instruments...

It is lunchtime in Hamburg. On the factory floor, under a sign that reads ‘Qualitats kontrolle’, men in workboots and overalls hold their lunchboxes and listen.

This is the Steinway & Sons factory, where the best pianos in the world are designed, constructed and shipped out across the globe. And it is indeed one of these pianos that is currently being played in the centre of the room, Beethoven’s Für Elise dancing from the fingertips of a concert pianist who has swapped the stage for the cement floor of the assembly line.

The workers, young and old, are mesmerised by the performance and it is clear that the company, founded in the mid-19th century – and its iconic instruments – continue to hit the right notes to this day.

Since Steinway’s inception in 1853, the system of designing and constructing their signature gloss black grands has remained startlingly consistent. And, with over 12,000 individual parts, the finest base materials and a build time of an entire year, it is a process that the 300 factory workers have refined to an art.

German native Guido Zimmermann was appointed as the company’s new managing director in 2017 and, as one of Steinway’s newest sons, he is keen to show the world how relevant and superior the brand’s pianos continue to be in the 21st century.

“Everybody in the world knows the name Steinway,” beams Zimmermann, adjusting the knot of his Steinway black tie. “And that is because we have three secrets. We’ve stuck with pianos, rather than diversifying out to other instruments, we use only the best materials, and we employ the most skilled workers.”

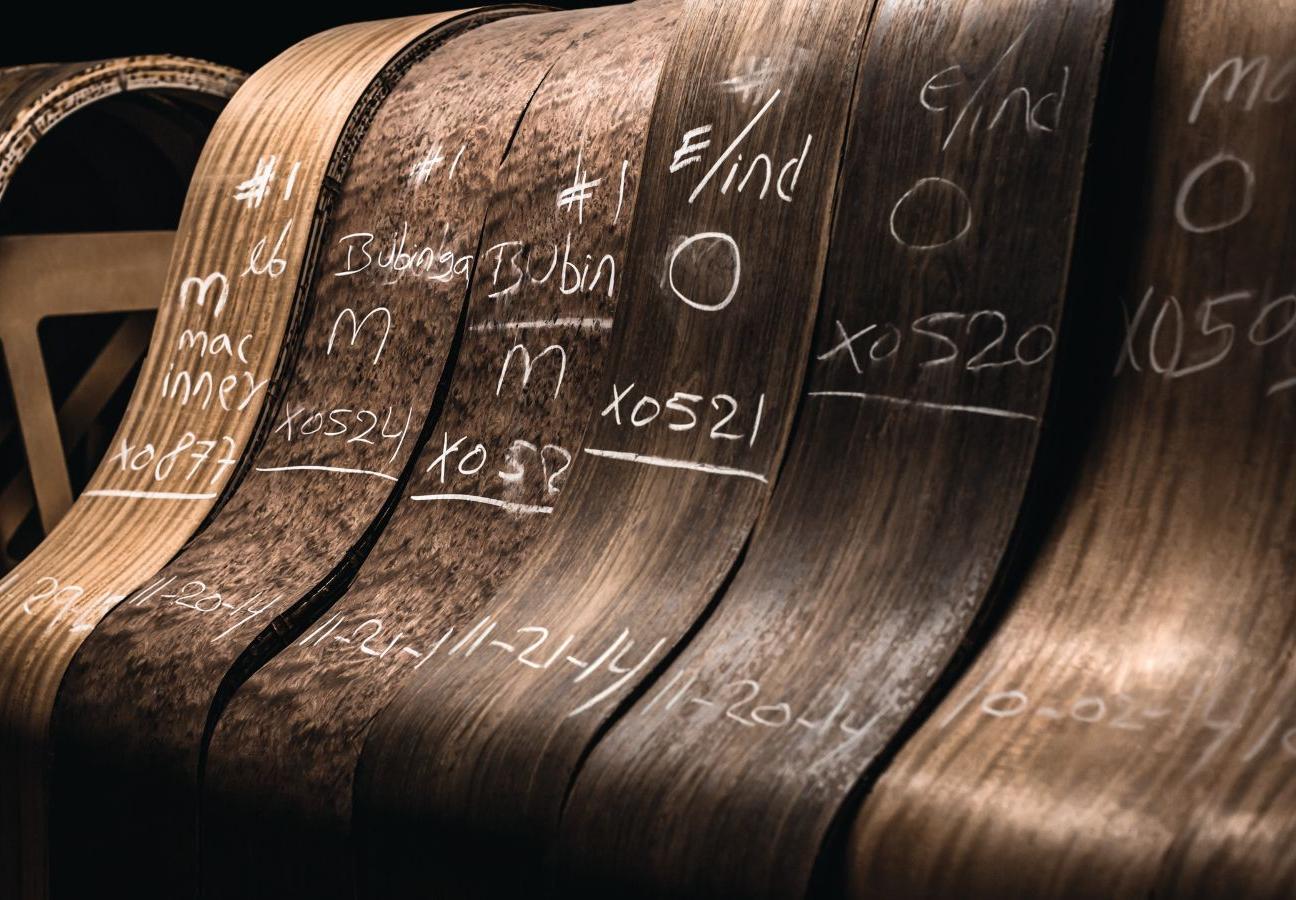

The workers are, indeed, incredibly impressive. At the beginning of the production line, a small team are working with metronomic precision. Equipped with buckets, brushes and aprons, they are gluing 20 long strips of maple and mahogany together to create the piano’s rim. Bonded in this way to increase flexibility, the wood is carried across the floor by five men and fastened into a heavy banding press, clamped into the iconic shape of a grand.

“Only 50 per cent of the wood Steinway orders actually makes it into a piano,” Zimmermann reveals, adding that 1,200 pianos are produced by this facility every year. “But nothing is wasted. The reject wood is used to heat the factory, or power the large sauna-like ovens that the dry the wood out before production can begin.”

The workers explain how the rim stays in the press for just three hours, before being taken to a humidity-controlled cellar for 100 days. The most important singular part of a grand piano, Steinway’s rims are distinct from those of other piano manufacturers. Whereas Yamaha and Bösendorfer first build the moving parts of a piano, Steinway work from the outside in, meaning that the inside workings must come second to the instrument’s aesthetics – without compromising on quality.

“Steinway are the inventors of modern piano building,” says Zimmermann. “We assemble in-house, with most parts – from the lid to the legs – also produced in Hamburg. The only part constructed in Germany, but not in this factory, is the keyboard.”

The only notable change in Steinway’s recent production can be seen in the keys. After eschewing ivory in 1989, the company committed themselves to finding the very best faux-alternative. Today, the polymer has been perfected to such an extent that even professionals can’t tell the difference.

Fast forward 100 days to the next stop along the production line, when the rims are ready to have any rough edges, quite literally, knocked off. Men stand, painstakingly sanding them smooth, removing any excess glue and adding hard wood for stability and strength.

“80 per cent of Steinway construction is by hand,” says Zimmerman. “Machines have only been introduced where safety, or precision, can be improved”.

“We don’t have a lot of secrets at Steinway anymore,” continues the managing director as we pass more chisel-wielding workers. “Other companies are free to use our patents, and they do. But not in the same order, or way that we do. A Steinway is more than just following a set of patents. A Steinway is the people who make it.”

These people, the workers of the Steinway factory, each have a specialist function. And, as many of the staff remain in the same job until they retire, most spend every day of their lives honing one or two unique skills.

Mr Sammann, the man tasked with creating the spruce soundboards that form the bottom of the pianos, is a prime example. He has spent the last 30 years in the same room, quietly working away on what he considers to be the most important part of these instruments. “The soundboard is the heart of the piano,” is all Sammann will say.

“We don’t have a lot of secrets at Steinway anymore…”

If the soundboard is the heart, then the iron-plate is surely the backbone. Shipped from the United States in a raw state, these large frames of skeletal metal are refined in Hamburg. A tiled area that resembles the back room of a butcher’s shop sees the plates hung by chains from the ceiling, whilst workers use high-powered jets to blast impurities off the iron and sluice them away through grates in the floor.

On another floor, and behind closed doors, the rims are sprayed. The thick, acrid smell of the signature black gloss creeps beyond the only window – a small porthole through which you can see a man both completely covered in overalls, and paint. It looks like a tough job, but is arguably the step that truly makes a Steinway a Steinway – over 90 per cent of the pianos sold are rendered in this highly-polished black finish.

From factory floor to spraying room, each stop along the production line is visually very different. One of the last, where the Steinways come to life, has hardwood floors – like those of a concert stage or theatre. “If the pianos were cars,” notes Zimmermann, “this is where we’d start the engines.”

One worker takes three days to fit the working parts into a Steinway grand, pressing each key 10,000 times and tuning the instrument. And many of these instruments spend their lives on stage floors like these, as over 1,800 artists, past and present, have featured on Steinway’s professional roster, including Cole Porter, Sergei Rachmaninoff, and Billy Joel.

The company will also accept one-off commissions, however unconventional, as images lining the corridors of the factory testify. One limited edition, the 300,000th instrument ever produced, is a grand with carved eagles for legs which today sits in the White House.

Even within their production range – from compact uprights to 9-foot grands – there are stunning special editions. The Crown Jewel collection, for instance, features diamond inlays and precious veneers – from East Indian Rosewood to Macassar Ebony. And Spirio, Steinway’s self-playing software, takes what could be considered a gimmick, and presents us with pure performance.

But, despite the air of exclusivity around the brand – Steinway’s new Paris flagship store opened earlier this year, and even the smallest pianos have price tags north of £10,000 – it is the workers who imbue the instruments with such precision and passion. Back on the factory floor, as the lunchtime concert draws to a close, rapturous applause makes their commitment clear.

So whilst the famed pianomakers may have stores stretching from Dallas to Dusseldorf, and have had customers from Lang Lang to Liberace, it is in this humble Hamburg factory where the true virtuosi can be found.

Want more factory tours? We took a spin around Tesla’s European mega-factory…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal member. Find out more here.

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.