Those familiar with the public school scene at Bristol University will not have been surprised to learn that Luke Osborne, son of George, the former Chancellor of the Exchequer and heir to the Osborne baronetcy, hosts a drum and bass night at an underground club. The 10-3am event, whose thoroughly undergraduate description is worth reading in full here, said it was “guaranteed to smack shades of shit out of your Tuesday night”. Young Osborne follows in a rich tradition of high born yahoos decamping to the southwest in search of chemical enlightenment and a passable mockney accent. Luke’s allusions to a “frenetiqué of absolute shit-housery” and “severely hallucinogenic enzymes” are hilarious, betraying the desire to convey that you are cool enough to know what drugs are. Like reading Adrian Mole, it’s a reminder of how cringe you were yourself at that age.

Still, this episode pales in comparison to the controversies his father has been embroiled in. George Osborne, 50, is a scandal magnet, and not just since he stepped down as an MP in 2017. At Oxford he was a member of the Bullingdon Club – the yin to the posho Bristolian bucket hat gurner’s yang – and attended tie-and-tails bashes that according to witnesses, descended into broken-plate and thrown-punch farces. One witness claimed Osborne was present when a Bullingdon member tried to snort lines of cocaine on an open-top bus. “I said to him: ‘You’re stupid, it’s blowing away’, and his response was: ‘I can afford it’.” This contemporary, quoted in the Observer, says he never saw Osborne indulge. Outside the Buller, he courted the sort of notoriety that is more expected of Oxford students. In editing one of the student newspapers, he printed part of one issue on hemp paper with the warning “Do not attempt to smoke it”.

Osborne started work at the Conservative Party a year after uni, and became an MP in 2001. Suggesting that Gordon Brown was “faintly autistic” and using MP expenses to pay for chauffeur fees as well as a country house and paddock in Cheshire were minor scandals that he weathered. But his first proper stink came in 2008 when he was accused of soliciting a donation from Oleg Deripaska, the Russian aluminium tycoon. There, on Deripaska’s yacht in Corfu, Osborne allegedly solicited a £50,000 donation, in violation of the laws against political contributions from foreigners. Yachtgate, as it came to be known, saw Osborne admit he made a mistake in meeting Deripaska, but denied trying to tap up one of the world’s richest men, claiming they spoke instead about Russian history over cups of tea.

Osborne in his Bullingdon hey-day, 1993

This was all practice for the fiascos that came after Osborne left frontline politics, having been sidelined when Theresa May became prime minister. Still an MP, he picked up a part-time job as an advisor to BlackRock, the giant American investment management firm. One day a week netted him a salary of £650,000. His job — which he took up six months after leaving his role as chancellor — was cleared by the public body that rules on business appointments. He also took up lucrative speaking engagements and the chairmanship of the Northern Powerhouse Partnership think tank.

He then started a job as editor of the Evening Standard newspaper, despite a lack of journalism experience beyond freelancing for a while after uni. This led to accusations that he thought the job of MP was beneath him. “The lack of respect he’s shown for his role as member of parliament is a disgrace,” said a Labour MP, reasonably questioning how his Cheshire constituents could expect to see their representative when he edited a daily newspaper 200 miles away in London. Osborne didn’t mind the criticism, he was having too much fun chucking rocks at Theresa May’s government with his free paper read by one million Londoners a day. One observer described him as “a nine-year-old boy on a sunny day, armed with a Super Soaker”.

They say you shouldn’t judge a man’s conscience by looking at his face, which is useful as the officious actuarial impression that Osborne gives off belied the unhinged comments he made about his rival in Number 10. He told more than one colleague at the Evening Standard that he would not rest until May “is chopped up in bags in my freezer”.

After leaving parliament, Osborne snagged more gigs: chairman of a panel of advisors to Exor, which owns Juventus and has major stakes in Ferrari and Fiat Chrysler. At one stage he had nine jobs: adviser to 9Yards Capital, his brother’s Bay Area VC fund, and a fellow at the McCain Institute, a think tank founded by the late John McCain. He is an honorary professor at the University of Manchester and had two roles at Stanford in California: as a distinguished visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution and a dean’s fellow at the business school.

Now he has left his role as the Standard’s editor and ditched his BlackRock gig to take up a new full time role as a partner at Robey Warshaw, a boutique Mayfair investment bank. There he will work on mergers and acquisitions – fondly termed “murders and executions” by the most famous fictional banker, Patrick Bateman. The bank only has 13 staff and has made profits north of £200m since opening eight years ago, according to reports. Firms like Robey Warshaw value discretion, so bringing Osborne into the fold might seem counterintuitive. Especially when one of his first deals involved advising EN+, a company set up by a blast from the past… Oleg Deripaska!

As one city specialist noted, Osborne “opens doors, but are they the right ones?” Osborne might have been chancellor, but he is new to investment banking. Will he be able to crack this new career? Or will his connections attract yet another controversy before long? Judging by the success of his son, the future Sir Luke Osborne, 19th baronet — in the world of drum and bass events — the Osbornes have a family knack for faking it till they’re making it.

Read next: Inside the Facebook whistleblower scandal

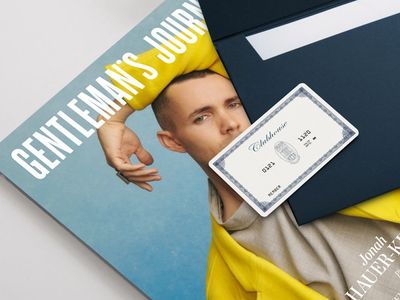

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.