Nothing ventured, nothing gained is a mantra that is drummed into all schoolchildren yet surprisingly few people are willing to take risks in business.

Following the herd is a lot easier than trying something new and radical that could flop. Indeed, it is possible to make a handsome profit without taking many risks, but the likelihood is that business will lack flair or originality. To build a genuinely pioneering company requires innovation and a willingness to push boundaries because, ultimately, it means one is willing to risk failure in pursuit of excellence and profit. It is those business leaders who have risked all and won that capture our imagination because they tend to be pioneers and mould-breakers.

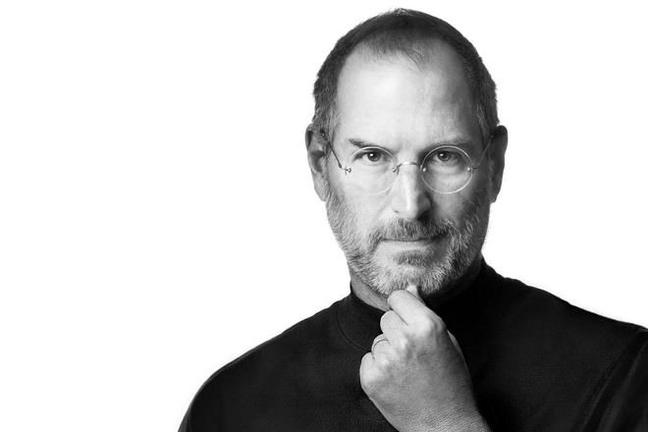

The Gentleman’s Journal has selected five business leaders who have shaped different industries from computing to high finance, from high street retailing to media. Apple founder Steve Jobs was an easy choice for our list because of his remarkable achievement in building the world’s biggest company and reshaping at least three areas of our lives: computing, music and phones. Jobs was a visionary who, from a young age, could foresee the way that technology would shape the future. But, crucially, he was also focused on the practical execution of his ideas. What’s more, as he admitted himself, being ousted from Apple at the age of 30 in a boardroom feud ended up helping him to take bigger, better risks when he returned a decade later. “It turned out that getting fired from Apple was the best thing that could have ever happened to me,” he recalled in his memorable Stanford University speech of 2005, “The heaviness of being successful was replaced by the lightness of being a beginner again, less sure about everything. It freed me to enter one of the most creative periods of my life.” It meant that when he came back to Apple, with the company on the verge of collapse, he brought tremendous focus and a passionate desire to launch new, innovative products, while at the same time being unafraid to kill off ideas that were not working.

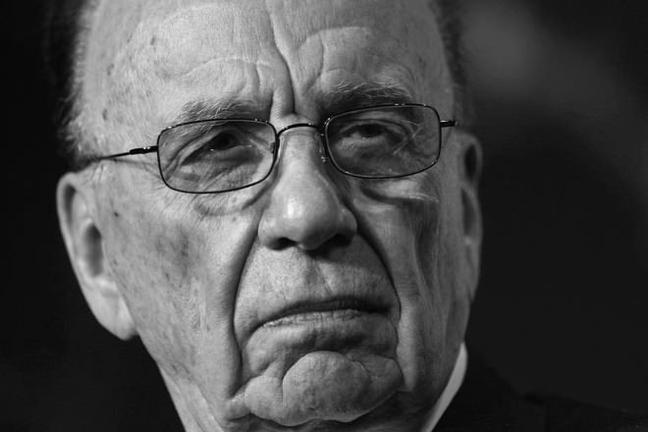

Media mogul Rupert Murdoch got on well with Steve Jobs and shared a similar mindset about being a “changemaker”. Unlike Jobs, who was adopted, Murdoch inherited wealth as part of a leading Australian family. But, interestingly, the time that that the owner of The Sun, The Times and the Fox TV and film business ended up risking it all was during the recession of the early 1990s, when he had just launched his pioneering satellite TV platform Sky in Britain. His global business, News Corporation, was heavily indebted and he had to go to over 100 banks to get a refinancing, which saved News Corp.

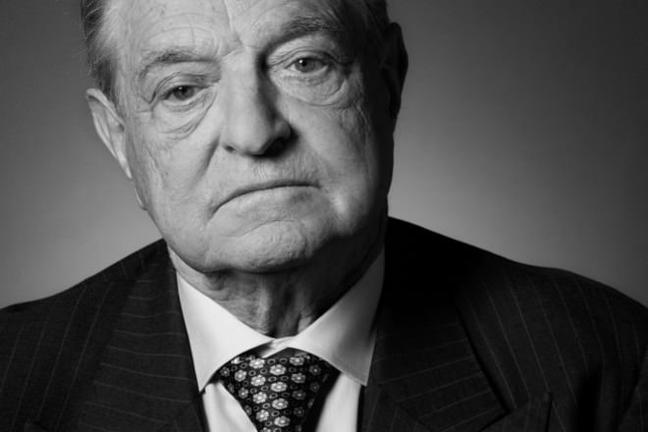

It is a reminder that tough economic times create disruption and risk – but also some of the best opportunities. Legendary investor George Soros recognised that when Britain was struggling to stay in the European Exchange Rate Mechanism in 1992. He took a giant bet against sterling on the basis that the UK would be kicked out and won. Sometimes the threat of financial collapse can be a great motivator as it creates a “burning platform” mentality, as Archie Norman, the man who turned around supermarket chain Asda two decades ago puts it. Unlike Jobs, Murdoch or Soros, who have an owner-manager mentality, Norman was a hired gun – the only man who applied to run Asda when it was on the brink of collapse and shareholders needed a saviour.

What Norman saw was not only that risk-taking was required to turn around the business but also it needed to be ingrained into its culture to sustain Asda in the future. “Success requires continuous renewal of energy, an organisation that’s constantly arguing with itself, that is driving forward and never satisfied,” he recalled recently. Some say Britain lacks the entrepreneurial restlessness that Norman has identified, especially compared to America. However, there is no doubt that the recession since 2007 and the rise and rise of digital technology has encouraged a new wave of digital start-ups in Britain like Mind Candy, the company behind kids’ games website Moshi Monsters, founded by Michael Acton Smith.

Steve Jobs, Computer Genius

Steve Jobs is arguably the greatest entrepreneur of the last 50 years, thanks to his creation of the iPhone, iPad, iPod and Mac, but it would be easy to forget the pitfalls he suffered earlier in his career. Jobs floated Apple on the stock market by the age of 24 but was fired at the age of 30 in a boardroom feud and spent a decade in the wilderness – although he managed to found animation studio Pixar, which showed he still he had the Midas touch. When he returned to Apple in 1997, the company’s future was bleak as it had a huge range of disappointing products and was losing $1 billion a year. “We were less than ninety days from being insolvent,” recalled Jobs. He took drastic and aggressive action, killing off 70 per cent of Apple’s product lines including the Newton personal digital assistant device. Many of Apple’s engineers were furious at what they saw as Jobs’ slash-and-burn tactics, which led to huge job cuts. “If Apple had been in a less precarious position, I would have drilled down myself to figure out how to make it work,” admitted Jobs to his biographer Walter Issacson. “By shutting it down, I freed up some good engineers who could work on new mobile devices. And eventually we got it right when we moved on to iPhones and the iPad.” Indeed his focus and willingness to take a risk on just a few innovative, beautifully designed products paid off almost immediately, with the release of the acclaimed iMac computer in 1998. As Issascon says in his biography, Jobs had “saved Apple”, which went on to become the world’s most valuable company by the time of his death in 2011.

George Soros, Investor

George Soros is the Hungarian-American financier who “broke the Bank of England”, making close to £1 billion with an extraordinary bet of $10 billion against sterling in 1992. Soros, then aged 62, was already a brilliant investor and speculator and had decided several years earlier that the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) was unsustainable. He built up his position against sterling over time, as he felt the British currency could not cope with being artificially yoked at a fixed rate to the German Deutschmark when the UK economy was cratering. So sure was Soros of his strategy that, in the words of Forbes magazine, “he was willing to bet the ranch”. He sold sterling “short” to the tune of seven billion dollars and bought the Deutschmark for six billion dollars and to a lesser extent bought the French franc. As a parallel play, Soros bought as much as $500 million of British shares while they were shorting sterling, figuring that equities often rise after a currency devalues. The Bank of England and prime minister John Major were forced to cave in as they learnt a painful lesson that global financial markets could be more powerful than a central Bank. Soros has continued to make big currency bets and hedges but never quite on the epic scale of his sterling coup.

Rupert Murdoch, Media Mogul

Rupert Murdoch is always impatient for change. He may have been born into one of Australia’s wealthiest families and inherited newspapers from his father but, even now at the age of 82, he is never satisfied with the status quo. He is always taking big bets, by launching TV channels and newspapers and closing down or selling off ventures that don’t work like social networking website MySpace (bought for $580 million), free newspaper The London Paper or iPad publication The Daily. One of his most successful creations is British satellite broadcaster Sky, which he founded in 1989 when Murdoch had the vision to see how satellite would mean a revolution in TV. However, it could well have turned out very differently when recession struck in 1990 and sharply rising interest rates heaped pressure on Murdoch. By the end of 1990, he was forced to merge Sky with rival British Satellite Broadcasting and his parent company News Corporation, which owned a string of global newspaper, TV and cinema interests, was in danger of collapse under $7bn of debts. It took a huge refinancing involving more than 100 international banks, including Midland Montagu in London, Citicorp in New York and Commonwealth Bank of Australia, to save Murdoch. Afterwards he joked: “We are the pin-up boys of the banks.” Sky is now a £7 billion-a-year jewel in his media empire but he still only owns 39 per cent and his hopes of taking full control have been stymied by the phone-hacking scandal. His decision to shut down the News of the World and, later, to launch the Sun on Sunday showed he is still capable of big, bold moves.

Archie Norman, Businessman,

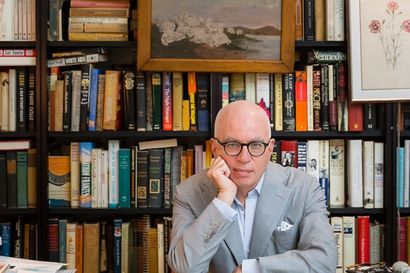

Archie Norman has been dubbed the turnaround king because of the job did he rescuing Asda, a supermarket chain that was on the verge of bankruptcy in 1991 when he was the only applicant for the chief executive’s job. At the time, the former McKinsyite and Harvard Business School alumnus was the 35-year-old finance director at retail conglomerate Kingfisher, owner of Woolworth’s, Comet and B&Q. But Norman decided he would take a chance on saving Asda, which was saddled with around £600 million in debts, unfavourable store locations and poor margins. “The advantage of being part of a failing or challenged company is there is a mandate for change, a burning platform,” recalled Norman, who talked to local store managers on the ground, sorted out the supply chain and focused on improving Asda’s corporate culture. City investors backed a £350 million rights issue and the turnaround worked as Norman and his young team, including Allan Leighton, who went on to chair Royal Mail, followed a formula of “being optimistic but having a fear of failure at the same time”. He was able to step back to a chairman’s role by 1999 when Asda was sold for £6.7 billion to Wal-Mart, making Norman and investors a small fortune. He did not enjoy as much success afterwards as a Tory MP and party grandee but has displayed all his turnaround skills again at ITV where he has tripled the share price since taking over as chairman in late 2009.

Michael Acton Smith, Digital Entrepreneur,

Michael Acton Smith is a poster boy for the East London technology scene with his mop of unruly hair just like his hit Moshi Monsters characters. He launched the virtual world of Moshi in 2008 and has gone on to have global success, launching countless physical spin-offs from playing cards to branded spectacles. But Moshi happened almost out of desperation. A serial entrepreneur, who enjoyed success in his twenties when he co-founded online electronics retailer Firebox in the 1990s, Acton Smith had an idea ten years ago to create an online game called Perplex City but it didn’t catch on and the £6 million he raised from investors almost ran out. By 2007, he had just £600,000 left. “I decided to have one last roll of the dice,” he told me. That meant dropping Perplex City and switching to Moshi, an idea he had first sketched on a piece of paper a year earlier. His inspiration was Pet Rock, a simple US toy that was a hit in the 1970s, and Japanese cartoon characters such as Pokemon. “I realised kids loved virtual pets.” Acton Smith launched Moshi as a free site in April 2008 but it was hard to gain momentum and “the business was on its last legs” as the banking crisis hit. So he decided to charge for premium services in 2009. It turned out kids did want the extras and some parents were willing to pay (it’s now £4.95 a month). By its fifth birthday this May, Moshi had 80 million users and had clocked up $250 million in gross retail sales worldwide.

Whether these five (very male) business leaders truly risked everything is an interesting question. With hindsight, taking a risk can look like a shrewd, calculated decision when the investment pays off – just as if it ends in failure it looks more like an ill-judged gamble.

What is certain is that persistence, attention to detail and a willingness to adapt to changing circumstances were all crucial in ensuring their long-term success – even if might have meant short-term failure. Some say men are willing to take bigger risks than women and that there might even be biological reasons for that, rather than just social conditioning. But the rise of the internet, mobile and digital technology is having such a disruptive effect on every area of our lives that it feels like the next generation of risk-takers will come from more diverse backgrounds.

By Gideon Spanier, media editor of the London Evening Standard.

This article has been taken from the autumn 2013 print edition of The Gentleman’s Journal print magazine. To read more like this, subscribe by clicking here.

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.