In 1949, when Alfred Winslow Jones dreamt up the hedge fund, he could never have imagined the financial phenomenon it was to become. Today, the industry is worth over £2.6trillion, remains largely unregulated and plays host to outrageous cults of personality whose pay packets make Goldman Sachs executives look like kids in a sweatshop.

“In most parts of finance, 90% of the success of your career rests on something that you have no control over,” says Lars Kroijer, author of Money Mavericks: Confessions of a Hedge Fund Manager. “So much of it is down to the movement of the economy and the markets. But the beauty of hedge funds is that you can make that go away.”

Primarily, that’s because hedge funds are less encumbered by regulation than other types of financial organisation. The founder of what has become recognised as the first ever hedge fund, Alfred Winslow Jones, spotted that there was money to be made from creating a ‘long-short’ equity fund that went short on overvalued stocks (essentially betting on them to lose value) and going long on equities that were likely to increase in value. That way, even in a falling market, it was possible to see good returns. Winslow Jones, a financial journalist, also borrowed money to invest. But since this and the practice of shorting was illegal for conventional funds, his was established as a limited partnership.

That was in 1949, but today the financial services industry has moved on – and what constitutes ‘a hedge fund’ is a less clear, partly because funds invest in a much wider range of asset classes – including commodity, currency, distressed and credit. A modern-day hedgie that I speak to jokes that the best definition of a hedge fund he has heard is: “a fee structure – with an investment idea attached as a secondary thought.” When we meet in his company’s discreet central London offices, he also asks to remain anonymous, so he’s referred to here as ‘Michael Jones’. “But,” he adds, “the fee structure might actually be the best way to define a hedge fund. The classic model is ‘two and 20’.” This means that a hedge fund typically takes a 2% fee for looking after an investor’s money. Then, on top of that, it takes a further 20% of any gains that are made as a result of its management of the fund and the investments that are made.

It’s widely acknowledged that these fees are high, so ‘hedgies’ are under pressure to prove their worth by making index-beating gains, but it’s easy to see how the profits for successful organisations and the people who run them can get rather big, rather quickly. The 25 top-earning hedge fund managers in the world last year made a combined total of $21bn – enough to make the $23m pay packet of Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein look like peanuts in comparison.

In the UK, a good chunk (5%) of the Sunday Times Rich List (of the 1,000 richest people in the country) is accounted for by people who made their money through hedge funds. The highest ranked this year [2014] was Alan Howard, who is thought to be worth £1.6bn.

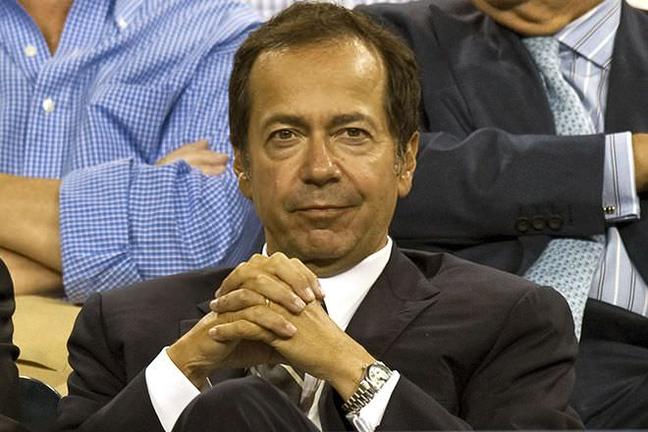

-John Paulson

Some ‘hedgies’ profited from the global financial meltdown. The most notable being John Paulson, who used credit default swaps to bet against sub-prime mortgage lenders in the US. According to Bloomberg Businessweek, he was personally paid almost $4bn in 2007, while his firm made $15bn. Some individual funds within the firm ended up with a six-fold return on investment. The move itself was, of course, a once-in-a-lifetime win for Paulson, but the fact that a select group of already wealthy financiers got richer from a series of events that caused untold misery for millions was not good PR.

It’s perhaps a reaction to this sort of story, as well as the general maturation of an industry that was once synonymous with the risk-taking ‘Masters of the Universe’, that hedge funds have now come to be regarded as less flashy than they once were. But the New York Times recently suggested that, somewhat ironically, this more conservative ethos might be the very thing that is powering the sector’s prodigious growth. According to a recent report by McKinsey, the global alternate investment market (which also includes real estate, commodities and private equity firms) is now worth $7.2 trillion, and hedge funds are the fastest growing part of it, swelling from $1.4 trillion in 2008 to be worth $2.6 trillion at the end of last year.

According to Jones, another part of the picture may be that the rise of ‘quants’ (funds that rely heavily on code, computer power and algorithms to make investment decisions) and the increasing prevalence of technology has lessened the importance of the type of fund managers who would attract investment in their funds through sheer “cult of personality”. However, he adds, there are still some “rock stars” whom everybody in the industry knows.

One is Raffaele Costa. Now the founder and CEO of his own firm, Tyndaris, the Sicilian made his name as deputy global head of sales at Man Group, but also thanks to his nautical alter ego, “Captain Magic” – a masked, piratical figure who held court on Costa’s ostentatiously appointed yacht, Sea Force One.

Jones also mentions an ex-CIA operative who has helped his employer to determine whether people presenting financial statements are telling the whole truth (“they raise a lot of money, actually”). Other well-known figures in London include Frenchman Emmanuel ‘Manny’ Roman, who became CEO of Man Group last year, and Belgian, Pierre Lagrange. The latter, a founding partner of GLG, set tongues wagging when he left his wife and three children in a record-setting £160 million separation. He later moved in with his boyfriend, Sudanese-born fashion designer Roubi L’Roubi, and the pair now own the country pursuits clothing label Huntsman. Australian-born Sir Michael Hintze is also widely recognised, but cuts a more traditional, establishment figure. His patronage of the arts (his fund CQS sponsors the Old Vic theatre and he donated £2m to the National Gallery, where a room now bears his name) has led to speculation that he might be in line to receive a peerage.

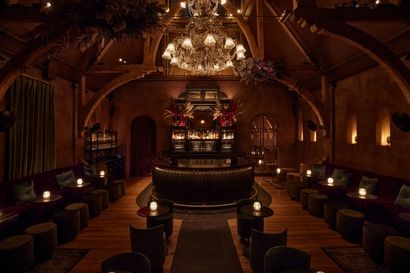

-Sea Force One

But among all the different personalities and reputations, is there something that the most successful hedge fund managers tend to have in common? “They have all been willing to trust their gut,” says Maneet Ahuja, who had in-depth meetings with Pierre Lagrange, John Paulson and nine other stars of the publicity-shy industry when researching her book, Alpha Masters: Unlocking the Genius of the World’s Top Hedge Funds. “And they make big bets, even when the market thinks they are wrong.”

Some people might add that the capacity to work hard is essential – Randall Dillard, for example, the managing director and chief investment officer at Liongate Capital Management, a fund of hedge funds, said earlier this year that young financiers working a 60-hour week were “not even in the game.”

But Lars Kroijer isn’t so convinced. “The hours are not longer than other parts of finance. If you wanted to work long hours, you’d be better off working for an investment bank – Morgan Stanley or somewhere like that. If you want genuine masochism, that’s where it’s at.” Stress, on the other hand, is a different matter. “The reason it’s so stressful is the marketplace,” says Kroijer. “The market prices are the score sheet and it is ever-changing, so you can go from being very, very rich to very, very poor in a short space of time. That can happen in venture capital or as an investment banker, but it takes a lot longer.” And Kroijer should know. His fund, Holte Capital, lost $10 million on one August day in 2007.

“If you take the world’s top 20 hedge fund managers – I’ve met about 10 of them – they’re genuinely very curious about the world around them. They care a lot about investing and some are almost professorial – nerdy types in the corner. Others are aggressive types: ‘I’ll stick a fork in you, if you don’t do what I say.’ The really successful ones will be good at motivating a team around them, because really big hedge fund managers don’t do all the investments themselves. But I don’t think there’s even a consistency about how they do that. Some are known as really intolerable people to work with, but just pay people a stonking fortune. So it’s not any one thing.”

But in the end, Kroijer says, you can find a common thread. The most successful people are “very smart and very hungry.”

“It’s a beautiful meritocracy,” he adds. “Even at a young age, real talent will probably be discovered quickly, [in hedge funds] you don’t have to first be beaten with a stick by someone at Goldman Sachs for 15 years. Having had many friends who have [been through that], it’s no fun at all.”

-Pierre Lagrange

What’s more, Kroijer says, the people who make the most money tend not to be motivated by money alone. “By and large they do it because they love the work and they find it really interesting – they could be a tenth as rich and still afford all their nice houses and nice cars, so they’re not doing it for that reason anymore. But the whole Playboy bunnies and helicopters thing is a myth more than reality. I’ve been around the industry a long time and I haven’t seen any of it.”

But maybe he just wasn’t looking in the right place. When I ask Michael Jones about the excess that many outsiders associate with the industry, he says that things have calmed down since what one might describe as its pre-crash heyday. “Back then, you would hear stories about the sales guys asking for brown envelopes. What they were used for – bribes, hookers, drugs – I don’t know. Today it’s different, although the banks still have parties for hedge funds pretty much every night. You could do it all the time if you wanted to. But we were never as bad as the brokers – sending private jets for people to go to Ibiza for the weekend and that sort of thing. Although…” He breaks off for a second. “I can remember some pretty good weekends.” But with that, comes my cue to leave. It’s time for him to go back to work.

Words: Edwin Smith

This article was taken from our Autumn 2014 issue. Subscribe to read more like this.

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.